Above: The then DMK Treasurer MK Stalin extending support to a bandh called by Tamil Nadu farmers associations on the Cauvery water dispute in 2016/Photo: UNI

While a landmark judgment has allocated more river water to Karnataka than Tamil Nadu, the political fallout could muddy the waters

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

The Supreme Court on February 16 brought the curtain down on the century-old inter-state Cauvery river water sharing dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, granting the former a greater share of the water while reducing that of the latter.

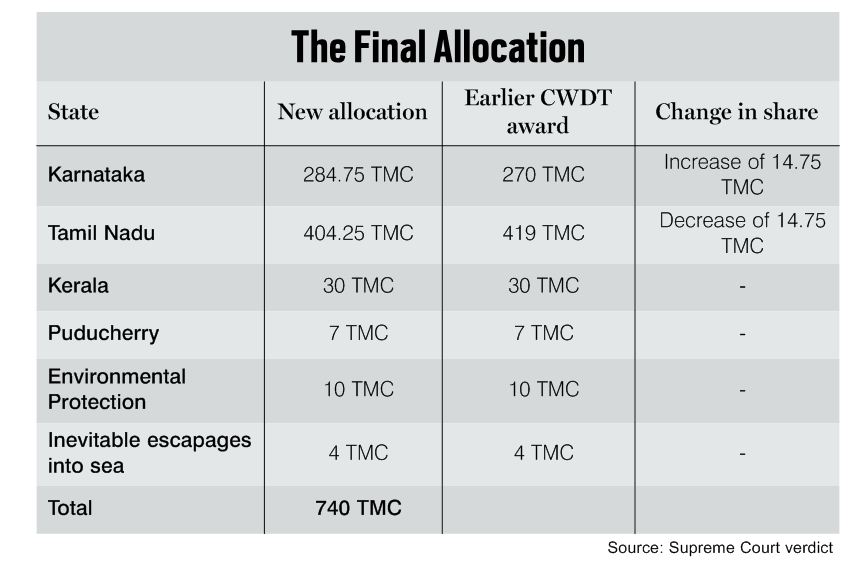

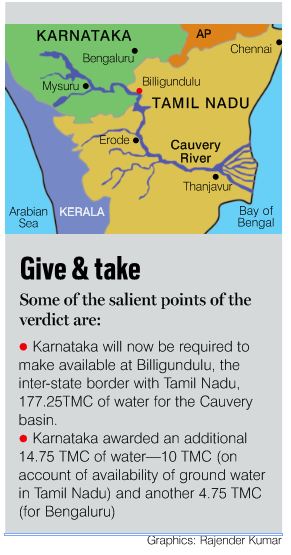

The verdict, delivered by the Supreme Court bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices Amitava Roy and AM Khanwilkar, revised the water sharing formula ordered by the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT) in 2007 for Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala and Puducherry—areas that fall within the Cauvery river basin—and concluded that Karnataka was entitled to “marginal” relief. The 465-page judgment authored by Chief Justice Misra grants Karnataka an additional 14.75 thousand million cubic (TMC) of Cauvery waters—10 TMC on account of availability of ground water in Tamil Nadu and another 4.75 TMC for drinking and domestic purposes for Bengaluru alone.

KARNATAKA WINS

The bench said it considered “Karnataka to be more deserving amongst the competing States” and ruled that the additional grant of water to it would be deducted from the quantum allocated by CWDT to Tamil Nadu in 2007. The Court also said that subject to the formulation of a scheme, the water allocation ordered by it will stand unchanged for the next 15 years.

In awarding Karnataka a greater share of Cauvery waters, the Court relied heavily on the state’s submission that the CWDT had “erred” in declaring that only one-third of Bengaluru fell in the river’s basin and should thus be largely excluded from rights over its waters.

Murky waters

The Cauvery water dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu has meandered for over 125 years and has seen many pacts:

- 1892 agreement: During the pre-independence era, the British had planned numerous projects to utilise Cauvery waters in the erstwhile princely state of Mysore and Madras Presidency. Famine in the 1870s brought these plans to a grinding halt. Following years of poor monsoon and drought-like situations, Mysore’s rulers sought to revive the British plans and reached an agreement with Madras Presidency in 1892 over sharing of the Cauvery waters.

- 1924 agreement: The 1892 agreement lasted till 1910 when both Mysore and Madras decided to construct dams in Kannambadi and Mettur, respectively. After a decade of arbitration by the British government, both signed an agreement in 1924—binding for 50 years —which allowed Madras to build the Mettur Dam and expand its agricultural area by 11 lakh acres from the then existing 16 lakh acres. Mysore was authorised to increase its irrigation area from 3 lakh acres to 10 lakh acres.

- 1974: The 1924 agreement expires. Karnataka claims it was unfair and announces a slew of reservoir projects along the Cauvery basin, irking Tamil Nadu and triggering violent protests in both states. TN urges the centre to set up a tribunal to resolve the dispute. In subsequent years, both file petitions in various courts over this dispute.

- June 1990: The centre sets up the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal (CWDT) following orders from the Supreme Court (SC).

- June 1991: CWDT orders Karnataka to release 205 tmcft of Cauvery waters to TN. Karnataka passes an ordinance to quash the CWDT award but the SC strikes it down.

- July 1993: TN chief minister Jayalalithaa announces her famous hunger strike at the MGR memorial in Chennai demanding CWDT-ordered share of the Cauvery water. Negotiations continue.

- August 1998: The centre constitutes the Cauvery River Authority (CRA) to ensure implementation of CWDT’s interim award.

- September 2002: CRA, chaired by then Prime Minister AB Vajpayee, directs Karnataka to release 9,000 cusecs (0.8 tmcft) of Cauvery water to TN. Unhappy, TN moves SC.

- February 5, 2007: CWDT announces the final award, says TN should receive 419 tmcft of water, more than double of the earlier interim order for 200 tmcft. The centre takes six years to make notification of the award public. Both states protest, demand greater share of water.

- August 2016: TN moves SC against the CWDT award; similar petition filed by Karnataka. SC orders Karnataka to release 15,000 cusecs of Cauvery water to TN every day for 10 days. Violent protests break out in Karnataka’s Mandya, Mysuru and Hassan districts.

- February 16, 2018: SC announces final order. Karnataka directed to release 177.25 tmcft of Cauvery water to TN from its inter-state Billigundulu dam. Karnataka will now have an enhanced share of 14.75 tmcft water per year, while TN will get 404.25 tmcft instead of the CWDT award of 419 tmcft.

It also held that the CWDT did not take into account Tamil Nadu’s stock of an “empirical” 20 TMC of groundwater and said that it would take into account at least 10 TMC of this groundwater and reduce it from the 192 TMC supplied to Tamil Nadu from Karnataka.

BENGALURU BIGGEST GAINER

Making it clear that the geographical location and “global status” of Bengaluru and its burgeoning requirement for ground and river water was instrumental in shaping the verdict, the bench said: “We are of the considered opinion that the allocation of water for drinking and domestic purposes for the entire city of Bengaluru has to be accounted for.” It said that it did not subscribe to the CWDT’s conclusion that the growing need for water in Bengaluru could be met by 60 percent of its groundwater supply.

Making it clear that the geographical location and “global status” of Bengaluru and its burgeoning requirement for ground and river water was instrumental in shaping the verdict, the bench said: “We are of the considered opinion that the allocation of water for drinking and domestic purposes for the entire city of Bengaluru has to be accounted for.” It said that it did not subscribe to the CWDT’s conclusion that the growing need for water in Bengaluru could be met by 60 percent of its groundwater supply.

This verdict comes at a crucial time for residents of Bengaluru—a significant number of whom are migrants from Tamil Nadu. In fact, a recent UN-backed study published by BBC had ranked Bengaluru second in a list of 11 cities globally that are facing the imminent threat of water scarcity by 2030. The first was Brazil’s Sau Paulo. The study says that Bengaluru “does not have a single lake whose water is fit for human consumption”.

The apex court also outlined a doctrine that could become the cornerstone for adjudicating on similar inter-state river water disputes in future. Observing that the “waters of an inter-State river passing through the corridors of the riparian States constitute national asset and cannot be said to be located in any one State”, the Court said: “No State can claim exclusive ownership of such waters or assert a prescriptive right so as to deprive the other States of their equitable share.”

The Court also held that the “right to flowing water is well-settled to be a right incident to property in the land and is a right publici juris of such character, that while it is common and equal to all through whose land it runs… each beneficiary has a right to just and reasonable use of it”.

It now remains to be seen whether Karnataka, which is jubilant over the verdict, will be abide by this doctrine when it argues for diverting the waters of Mahadayi river to its Malaprabha basin and thereby reduce Goa’s share of water from this river. This dispute too has been going on for decades.

POLITICAL FALLOUT

With the apex court’s verdict, the decades-old legal battle between the two states appears to have ended. However, the political fallout will start unravelling now. Karnataka goes to polls in April-May and the judgment comes as a massive shot in the arm for the Congress government of Siddaramaiah. The upcoming poll campaign will see him using the verdict as a major achievement of his government, especially in south Karnataka which stands to benefit the most from the increased water allocation. The verdict will help him steal a march over his political rivals in south Karnataka districts, especially against former Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda’s JD(S) which enjoys huge support among the Vokkaligas (state’s politically crucial farming community) in this region.

But in Tamil Nadu, where the ruling AIADMK under chief minister E Palaniswamy is struggling to keep his party and government together in the face of a rebellion led by TTV Dinakaran, the verdict has the potential of spelling political and social anarchy.

The political class in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu has been cautious in responding to the verdict, with the obvious exception of a sense of triumph among Kannadiga leaders. The law and order situation in Tamil Nadu continues to be on the edge.

Union water resources minister Nitin Gadkari has been trying to pacify Tamil leaders by selling them a new dream—that of interlinking the Godavari river with the Cauvery in Tamil Nadu to meet the water requirements of the state. This is easier said than done as river inter-linking projects have largely failed to take off due to various legal, environmental and social hurdles.

If violent protests that have been witnessed in the past due to the water sharing dispute rear up their ugly head again, it remains to be seen how the political brass in both states and at the centre will deal with the situation. They must ensure that things do not spiral out of control.