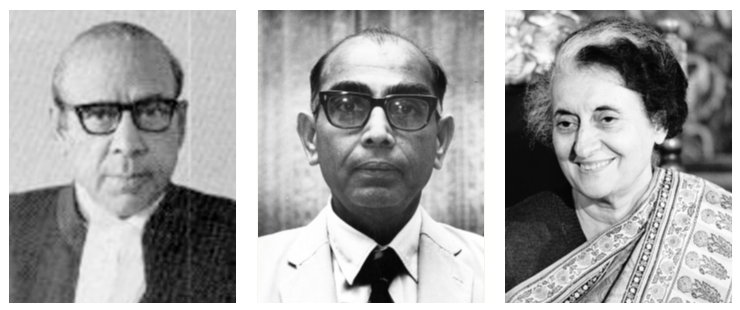

(L to R) Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra; the Supreme Court of India; Justice Ranjan Gogoi, the next in line to become CJI

With the turmoil in the top court, questions have cropped up whether Justice Ranjan Gogoi will be elevated to the top post by Chief Justice Dipak Misra when he retires in October

~By Vinay Vats

It is the function of the judiciary to maintain the rule of law in the country and see that the constitution is strictly followed. Article 124(1) of the constitution provides for establishing a Supreme Court as the apex body of the unified judicial system of India.

To enable the judiciary to discharge its functions effectively, it requires independence. However, if the Executive starts influencing its working, it can lead to problems.

One area where the judiciary of any country maintains its independence is in the selection and appointment of judges. If this function is given to the Executive, there are chances that the independence of the judiciary will be in danger. How-ever, various judgments by the Supreme Court in the past have made one thing very clear—the Executive cannot appoint any high court or Supreme Court judge without consulting the chief justice of India. It is also clear that the chief justice along with four senior-most judges of the apex court has to recommend a suitable name to the president.

Looking at the present scenario where Chief Justice Dipak Misra is retiring in October and the next in line is Justice Ranjan Gogoi—one of the four judges who was part of the “revolt” against the chief justice—is it likely that he will not be appointed to the top judicial post? What if the present chief justice does not recommend his name? Will it give rise to a constitutional crisis?

Anticipating such a situation, the constitution-makers framed Article 126 which talks about a situation where the chief justice is unable to perform his duties. It provides for the appointment by the president of an acting chief justice who will then recommend the name of the seniormost judge as chief justice of India.

A situation has never arisen when an acting chief justice had to be appointed to carry out the duties of the office of chief justice. However, before Independence, in 1943, when the federal courts of India were in existence, Srinivasa Vardachariar was appointed the acting chief justice of India for 43 days. Federal courts existed from September 1, 1937 to January 26, 1950; the Supreme Court came into existence on January 26, 1950.

In fact, the history of the appointment of Supreme Court judges and the chief justice of India can be bifurcated into two eras—one pre-1993 and the other, post-1993.

PRE-1993

During the pre-1993 era, the views expressed by the chief justice were not binding on the Executive. The final decision to appoint Supreme Court judges was left to the Executive.

The president would appoint judges to the Supreme Court like any other matter on the advice of the concerned minister—in this case, the law minister. The practice was to appoint the seniormost judge of the Supreme Court as the chief justice of India.

However, this practice was criticised in the 14th Law Commission Report of 1958 on the ground that the chief justice of India should not only be an experienced person but also a competent administrator and hence, elevation on the basis of seniority should be done away with.

However, the government did not act on this recommendation for a long time as it was afraid of allegations of tampering with judicial independence. But in 1973, Indira Gandhi’s government departed from procedure and appointed Justice AN Ray as the chief justice of India by surpassing three seniormost judges. This led to the resignation of the three in protest and raised serious questions about the independence of the judiciary. No one believed that the government might have acted on the recommendation of the 14th Law Commission Report.

The said appointment was even challenged in the Delhi High Court but was dismissed. Even if it was entertained, Justice Ray would have been appointed again on the basis of seniority as the other senior judges had resigned.

Deviation from this practice was again seen in 1976 when Justice MH Beg was appointed chief justice by surpassing Justice HR Khanna who was the seniormost. This too led to the resignation of Justice Khanna in protest.

However, after this incident, the rule of seniority was followed till date.

POST-1993

As far as the appointment of Supreme Court judges is concerned, the Constitution only says that the president should consult the chief justice of India and other judges he may deem fit under Article 124(2). There was no provision which made it clear as to whose opinion would finally prevail and what would happen in case of a difference of opinion.

In SP Gupta vs Union of India [1982], the Supreme Court held that the word “consultation” means the same as it is mentioned in Article 212 and Article 222 of the Constitution. This meant that the ultimate power to appoint judges is vested with the Executive. Subsequently, in SC Advocate-on-Record Association vs Union of India [1993], a nine-judge bench of the top court with a 7-2 majority held that the chief justice will have primacy in the appointment of judges of the Supreme Court and high courts.

It was also held that the appointment of the chief justice shall be done on the basis of seniority.

It remains to be seen as to what course the present chief justice takes to appoint his successor.