In a big relief to all Indians, the Supreme Court has thrown its weight behind the right of an individual to privacy and called it a fundamental right. This has far-reaching implications for every aspect of daily life

~By Vinay Vats

In a landmark judgment on August 24, a nine-judge bench of the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that individual privacy is a fundamental right. It said it was an intrinsic part of right to life and personal liberty and was guaranteed by the constitution. The ruling will touch the daily lives of 134 crore Indians and will affect the centre’s move to make Aadhaar mandatory for social welfare benefits, collection of personal data and Section 377 which criminalises homosexuality, among other things.

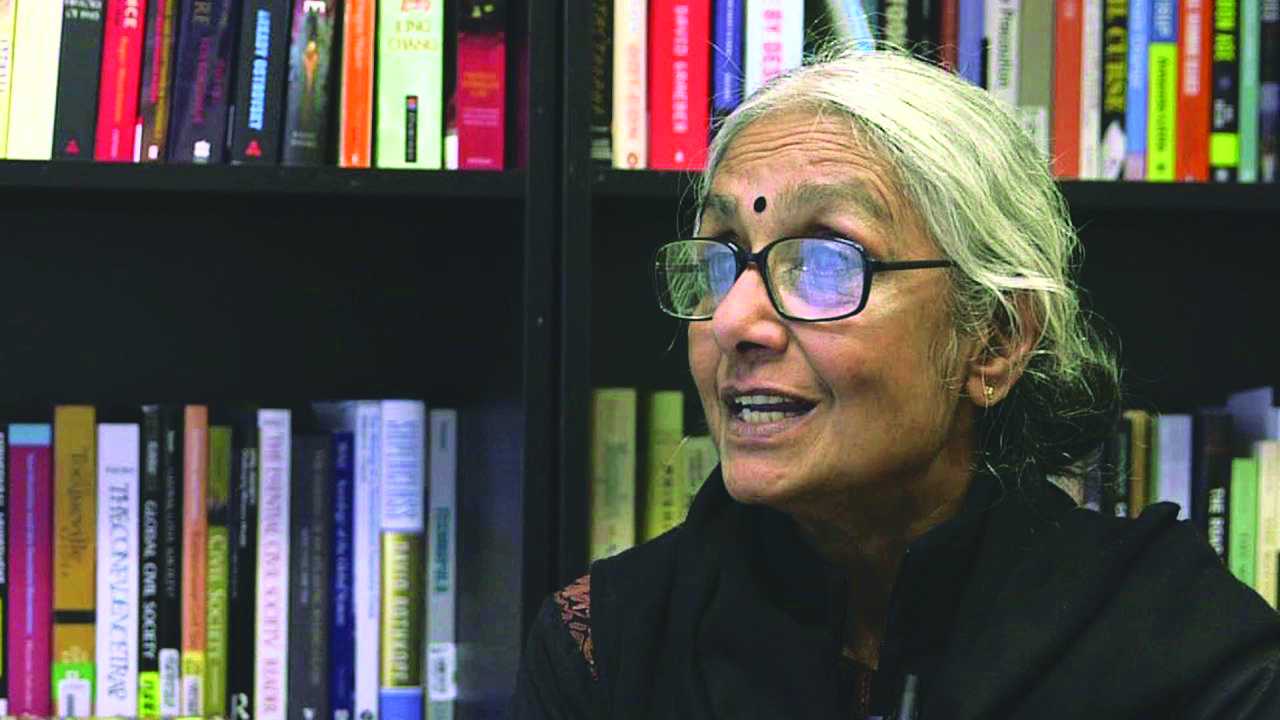

The judgment was delivered on a PIL filed by former Karnataka High Court Judge KS Puttaswamy in 2012, challenging the Aadhaar scheme. After this, more than 20 cases were filed on the said issue and the Supreme Court clubbed all of them to the main case. These cases include petitions by Col Mathew Thomas, activists Aruna Roy, Bezwada Wilson, Nikhil Dey and many others.

Six separate but concurrent judgments were written by the nine-judge bench on the issue. The bench was headed by Chief Justice of India JS Khehar, and included Justices J Chelameswar, SA Bobde, RF Nariman, RK Agrawal, AM Sapre, DY Chandrachud, Sanjay K Kaul and S Abdul Nazeer.

As per this historic judgment, the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as a part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the constitution. It said the decision in MP Sharma and Kharak Singh cases, which hold that the right to privacy is not protected by the constitution stand over-ruled.

The detailed judgment running into 547 pages should be seen against earlier judgments. These include:

- MP Sharma v Satish Chandra (1954): Right to privacy is not a fundamental right.

- Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh (1963): Right to Privacy is not guaranteed under our constitution.

- Govind v State of Madhya Pradesh (1975): SC accepted a limited fundamental right to privacy but observed that it is not absolute and reasonable restrictions can be imposed.

- Maneka Gandhi v Union of India (1978): Supreme Court laid down a number of provisions which made “right to life” or “personal liberty” more meaningful.

- R Rajagopal v State of Tamil Nadu (1995): Right to privacy of his own, his family, marriage, motherhood, procreation and right to be let alone is guaranteed under Article 21 of the constitution and no one can publish above matters without his permission.

- People’s Union for Civil Liberties v Union of India (1997): Right to privacy is a part of right to life and liberty enshrined under Article 21.

JUDGES’ COMMENTS

Justice Chandrachud, speaking for himself, Chief Justice Khehar, Justices Nazeer and Agrawal discussed the issue in a mammoth detailed judgment running into 265 pages, which occupied half of the 547-page judgment. He bifurcated the issue under 20 heads, which include earlier judgments, origin and evolution, jurisprudence and comparison of right to privacy with other countries. He termed privacy as the reservation of a private space for the individual and described it as the right to be let alone. The concept is founded on the autonomy of the individual. He said privacy of the individual was an essential aspect of dignity which had an intrinsic as well as instrumental value. As an intrinsic value, human dignity is an entitlement or a constitutionally protected interest in itself. In its instrumental facet, dignity and freedom are inseparably intertwined, each being a facilitative tool to achieve the other.

While overruling the judgment in MP Sharma, Justice Chandrachud wrote that the earlier court only looked at the issue on the basis of Art 20(3) of the constitution but overlooked whether right to privacy would arise from any of the other provisions of the rights guaranteed by Part III including Article 21 and Article 19. Similarly, he overruled Kharak Singh, as its reliance on the decision of the majority in Gopalan is not reflective of the correct position in view of the decisions in Cooper and in Maneka. He observed right to privacy was constitutionally protected by the guarantee of life and personal liberty in Article 21, but like other fundamental rights, it is also not absolute. Any law encroaching this right will have to meet the touchstone of reasonable restrictions. However, in his judgment, the issue of “data protection” was left un-touched with direction to the Union government to look into it. He observed that the government had already initiated the process of reviewing the entire area of data protection by constituting a committee chaired by Justice BN Srikrishna, a former judge of the Supreme Court.

Justice Sanjay Kaul observed that technology has made it possible to enter someone’s house without knocking his door. Privacy is the key to freedom of thought.

Justice Chelameswar divided the issue into three questions: Is there any Fundamental Right to privacy under the constitution? If it exists, where is it located and what are the contours of such right? While overruling MP Sharma and Kharak Singh by giving similar reasoning as Justices Chandrachud and Nariman, he observed that the former failed to examine whether the right of privacy is implied in any other fundamental right guaranteed under Articles 21, 14, 19 or 25.

He also observed that the expression liberty in Article 21 was wide enough to take in not only various freedoms enumerated in Article 19(1) but also many others which are not enumerated.

INDIVIDUAL’S ENTITLEMENTS

Justice Bobde while overruling the MP Sharma and Kharak Singh judgment, observed that in the former case, the conclusion was arrived at without enquiry into whether a privacy right could exist in our constitution and it also wrongly interpreted the United States Fourth Amendment. In his view, every individual is entitled to perform his actions in private. In other words, he is entitled to be in a state of repose and to work without being disturbed, or otherwise observed or spied upon. The entitlement to such a condition is not confined only to intimate spaces such as the bedroom or the washroom, but goes with a person wherever he is, even in a public place. He also observed “that it is not possible to truncate or isolate the basic freedom to do an activity in seclusion from the freedom to do the activity itself. The right to claim a basic condition like privacy in which guaranteed fundamental rights can be exercised must itself be regarded as a fundamental right. Privacy, thus, constitutes the basic, irreducible condition necessary for the exercise of ‘personal liberty’ and freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution. It is the inarticulate major premise in Part III of the Constitution.”

As per this historic judgment, the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21.

Justice Nariman held that the right to privacy is a fundamental right and bifurcated it into three aspects:

i) Privacy that involves the person i.e. when there is some invasion by the State of a person’s rights relatable to his physical body, such as the right to move freely

ii) Informational privacy which does not deal with a person’s body but deals with a person’s mind, and therefore recognises that an individual may have control over the dissemination of material that is personal to him. Unauthorised use of such information may, therefore, lead to infringement of this right

iii) The privacy of choice, which protects an individual’s autonomy over fundamental personal choices.

However, he also observed that such right is not absolute and subject to reasonable regulations by the State to protect its legitimate interests or public interest.

NATURAL RIGHT

Justice Sapre said it was not possible for the framers of the constitution to incorporate each and every right of an individual in Part III of the constitution and the Supreme Court had from time to time interpreted these in a different manner.

He observed that “right to privacy of any individual” was essentially a natural right. Such right remains with the human being till he breathes his last. He also observed that it has multiple facets and one cannot have a straight-jacket formula for it. It has to go through case-to-case development whenever any citizen raises his grievances.

Justice Kaul observed that the right to privacy cannot be diluted as it is an inherent right and is not given by someone but it already exists. Right to privacy is available not only against the State, but the State has to ensure that same is not violated by non-state actors. Technology has made it possible to enter someone’s house without knocking his door. Privacy is also the key to freedom of thought. A person has a right to think. However, he also talked about reasonable restrictions to this right.

Right to Privacy Abroad

Privacy uses the theory of natural rights, and generally responds to new information and communication technologies. In the US, an article in the December 15, 1890 issue of the Harvard Law Review, written by attorney Samuel D Warren and future US Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, entitled “The Right to Privacy”, is often cited as the first implicit declaration of a US right to privacy. Warren and Brandeis wrote that privacy is the “right to be let alone”, and focused on protecting individuals. This approach was a response to technological developments of the time such as photography, and sensationalist journalism, also known as “yellow journalism”.

Privacy rights are inherently intertwined with information technology. In dissenting opinion in Olmstead v United States (1928), Brandeis relied on thoughts he developed in his 1890 article “The Right to Privacy”. But in his dissent, he urged making personal privacy matters more relevant to constitutional law, going so far as saying “the government [was] identified…as a potential privacy invader”. He writes: “Discovery and invention have made it possible for the Government, by means far more effective than stretching upon the rack, to obtain disclosure in court of what is whispered in the closet.” At that time, telephones were often community assets, with shared party lines and the potentially nosey human operators. By the time of Katz, in 1967, telephones had become personal devices with lines not shared across homes. In the 1970s, new computing and recording technologies began to raise concerns about privacy, resulting in the Fair Information Practice Principles.

In recent years, there have been only few attempts to define a “right to privacy”. In 2005, students of the Haifa Center for Law & Technology asserted that in fact the right to privacy “should not be defined as a separate legal right” at all. By their reasoning, existing laws relating to privacy in general should be sufficient. Other experts, such as William Prosser, have attempted, but failed, to find a “common ground” between the leading kinds of privacy cases in the court system, at least to formulate a definition.[5] One law school treatise from Israel, however, on the subject of “privacy in the digital environment,” suggests that the “right to privacy should be seen as an independent right that deserves legal protection in itself.”

The 1890 Warren and Brandeis article “The Right To Privacy”, is often cited as the first implicit declaration of a US right to privacy. Strict constructionists argue that no such right exists (or at least that the Supreme Court has no jurisdiction to protect such a right), while some civil libertarians argue that the right invalidates many types of currently allowed civil surveillance (wire tapes, public cameras, etc.).

Most states of the US also grant a right to privacy and recognise four torts based on that right:

- Intrusion upon seclusion or solitude, or into private affairs;

- Public disclosure of embarrassing private facts;

- Publicity which places a person in a false light in the public eye; and

- Appropriation of name or likeness.

On March 11, 2015, Intelligence Squared US, an organisation that stages Oxford-style debates, held an event centered on the question, “Should the US adopt the ‘Right to be Forgotten’”. The side against the motion won with a 56 percent majority.

In the UK

Privacy in English law is a rapidly developing area that considers in what situations does an individual have a legal right to informational privacy—the protection of personal or private information from misuse or unauthorised disclosure. Privacy law is distinct from laws such as trespass or assault. Such laws are generally considered part of criminal law or the law of tort. Historically, English common law has recognised no general right or tort of privacy, and was offered only limited protection through the doctrine of breach of confidence and a “piecemeal” collection of related legislation on topics like harassment and data protection.

The introduction of the Human Rights Act 1998 incorporated into English law the European Convention on Human Rights. Article 8.1 of the ECHR provided an explicit right to respect for a private life. The Convention also requires the judiciary to “have regard” to the Convention in developing the common law.

The earliest definition of privacy in English law was given by Thomas M Cooley who defined it as “the right to be left alone”. In 1972, the Younger Committee, an inquiry into privacy stated that the term could not be defined satisfactorily. Again in 1990 the Calcutt Committee concluded that: “nowhere have we found a wholly satisfactory statutory definition of privacy”.

There is currently no freestanding right to privacy at common law. This point was reaffirmed when the House of Lords ruled in Home Office v Wainwright (a case involving a strip search undertaken on the plaintiff Alan Wainwright while visiting Armley prison). It has also been stated that the European Convention on Human Rights does not require the development of an independent tort of privacy.

In the absence of a common law, right to privacy in English law torts such as the equitable doctrine breach of confidence, torts linked to the intentional infliction of harm to the person and public law torts relating to the use of police powers have been used to fill a gap in the law. The judiciary has developed the law in an incremental fashion and has resisted the opportunity to create a new tort.

—By Nikhil Pandey

CLUTCH OF PILs

This judgement was a fallout of many PILs filed in this regard. These included:

- Justice KS Puttaswamy (Retd) and Anr vs Union of India and Ors: Filed first in the series of cases in 2012 by a former Karnataka High Court judge who challenged the government order mandating use of Aadhaar for Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, Pension scheme, Public Distribution System, Prime Minister’s Jan-Dhan Yojana and LPG.

- S Raju versus the Deptt of Finance Rep by Secy: Transferred from the High Court of Judicature at Madras in 2013, it raised the issue of the effect of the Aadhaar Scheme on the federal structure of the State.

- Vickram Crishna and Ors Vs Unique Identification Auth. of India and Ors: Transferred from the High Court of Bombay in 2013, it raised the issue of violation of right to privacy in collection of data under Aadhaar Scheme.

- Aruna Roy and Anr vs Union of India and Ors: Filed in 2013 against linking of Aadhaar Scheme to various welfare schemes.

- SG Vombatkere and Anr vs Union of India: Filed in 2013 against mandatory linking of Aadhaar for filing IT returns.

- Nagrik Chetna Manch vs Union of India: Filed in 2013 against government notification of mandating Aadhaar card for ration, capital subsidy, Digital India programme, voter ID, school admissions, etc.

- Mathew Thomas Versus Union of India Ministry of Finance: Filed in 2015, it raised the issue of data sharing and national security posted due to Aadhaar.

- SG Vombatkere and Anr vs Union of India and Anr: Another PIL filed by SG Vombatkere against collection of biometrics by private parties.

- Shantha Sinha and Anr vs Union of India and Anr: Filed in 2017, it challenged mandatory use of Aadhaar for the government’s social welfare schemes like scholarships, Right to Food and mid-day meal in schools.

Though the right to privacy issue rose from matter relating to the constitutional validity of the Aadhaar Scheme, even after final adjudication of the issue, the fate of Aadhaar is uncertain. It is evident from the above six separate but concurrent judgments that the efforts made by Justices Chandrachud and Nariman in writing the judgment have been utilised by all other judges. Every citizen of India will be thankful to them for gifting them a new set of fundamental rights.

Meanwhile, the issue of whether Aadhaar violates the right to privacy will still have to be dealt with. Nonetheless, this is a moment of triumph and celebration of the assertion of citizens’ rights. One has to hail the fight put up by numerous activists and lawyers who made it possible to stand up against a dominant state. Lessons of the past cannot easily be forgotten. The Court is supreme and so is freedom.

—The writer is an advocate