The fate of GM mustard hangs in the balance with the centre yet to take a final decision on it. This has forced many private agri-biotechnology companies to scale down research and operations

~By Vivian Fernandes

With the Genetic Engineering Appraisal Committee (GEAC), a body under the Ministry of Environment and Forests, recommending the release of genetically modified Dhara Mustard Hybrid-11 (DMH-11) on May 11, a milestone has been crossed. If the advice is accepted by the Union environment ministry and commercial cultivation is allowed, India’s agri-biotech industry will get a boost. But the investment outlook will still be clouded by concerns about the respect for intellectual property rights.

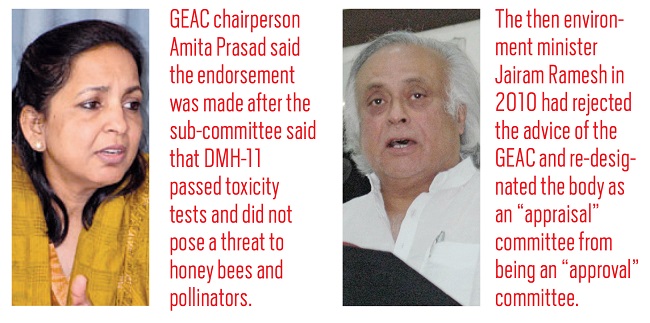

Will the ministry reject the advice of GEAC? Environment minister Jairam Ramesh did that in 2010 with regard to fruit and shoot borer resistant Bt brinjal. He imposed a 10-year moratorium on its release and re-designated the GEAC as an “appraisal” committee from an “approval” committee. B Sesikaran, former director of Hyderabad’s National Institute of Nutrition, recalls that after he had appraised Ramesh about the safety of Bt brinjal, the minister had said that “you have made a technical presentation, now let me take a political decision”. Sesikaran is currently a member of GEAC.

TREADING CAREFULLY

If the NDA government follows Ramesh’s example, it would please anti-GM activists as well as a lobby in the RSS, including its affiliate, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch, which is opposed to GM crops. But he would undermine the GEAC. The ministry seems to be treading carefully. A press statement explaining the reasons why GEAC recommended DMH-11 for cultivation was supposed to be released on May 12. But it was not done as the ministry wanted more discussion.

With little hope of approvals, BASF has shut its rice improvement programme based on genetic engineering in TN. Bayer Crop Science had stopped similar efforts in vegetables

FAQs on GM mustard, which had been posted prominently on the ministry’s website, were withdrawn by evening. Those who are sceptical about the ministry endorsing the GEAC’s decision see these as ominous signs. However, GEAC chairperson Amita Prasad has clarified that the FAQs will be uploaded after grammatical wrinkles are ironed out.

It is possible that their fears are overblown. If the government was hesitant, it would have asked the GEAC to play for time. The environment ministry would not have filed a strong affidavit last October in the Supreme Court against activists who wanted the commercial release of GM mustard stayed. In the affidavit, the ministry had asked the Court to dismiss the activists’ petition with “exemplary costs”. They were “strongly motivated ideologically”, it said and wanted to “derail and hijack” the regulatory process. “All public health-related issues have been adequately addressed for GM mustard through the regulatory pipeline process as per the rules,” Lok Sabha had been told last November.

SAFETY FIRST

The GEAC has recommended release for four years with conditions like post-release monitoring. Prasad said the endorsement was made after the sub-committee said DMH-11 passed toxicity tests and did not pose a threat to honeybees and pollinators. Herbicide tolerance was neither necessary for cultivation nor recommended. It also did not create new allergies. “No government will put its people to risk,” Prasad added.

Even if the ministry goes along, the Supreme Court’s permission would still be needed for commercial release. Last October, the Court had stayed its release for one year and the government had given an assurance that its prior permission would be taken.

Even if the ministry goes along, the Supreme Court’s permission would still be needed for commercial release. Last October, the Court had stayed its release for one year and the government had given an assurance that its prior permission would be taken.

Commercial cultivation of GM mustard would boost the morale of the Indian agri-biotechnology industry, which has not seen any new crops being approved after Bt cotton in 2002. GM mustard would be the first food crop, though Bt cottonseed oil is consumed in huge quantities and milk cattle are fed with Bt cottonseed oil cake. India also imports GM soybean and canola oils.

SLOW MODE

With little hope of approvals, German chemicals major BASF has shut its rice improvement programme based on genetic engineering in Tamil Nadu. Bayer Crop Science had stopped similar efforts in rice, canola and vegetables. Dupont Knowledge Centre has laid off plant biotechnologists in Hyderabad. Advanta, an Indian seeds company, had also scaled down its agri-biotech research efforts.

If the ministry goes along, the Supreme Court’s permission would still be needed for commercial release. Last October, the Court had stayed its release for one year

Last year, Monsanto withdrew its application for release of insect resistant Bt cotton stacked with the herbicide tolerance trait. It has decided against introducing Bollgard III, an advanced version of insect-resistant cotton. It is unlikely to introduce insect-resistant and herbicide tolerant corn as well.

Private agri-biotechnology research companies have been shaken by the government’s disregard for intellectual property rights. In May last year, the agriculture ministry waived patents on Bt cotton using the Essential Commodities Act. The draft guidelines were swiftly withdrawn, but the 70 percent reduction in trait fees made by the government through a price control order has hurt Mahyco Monsanto Biotech badly. Companies ask why they should bring patented traits to India if they cannot profit from them.

In March, the Delhi High Court upheld the government’s right to fix fees for patented traits, over-ruling the rights of the patent holders. It also revoked the termination of a sub-licence agreement by Mahyco Monsanto Biotech for non-payment of trait fees, and said the agreement should abide by government guidelines.

A division bench of the High Court has stayed the order on appeal, but it is unlikely to remove the cloud on the investment outlook. The government itself seems to be privileging breeders’ rights over those of patent holders. Unless they get a strong reassurance, private agri-biotech companies are unlikely to make in India.

—The writer is editor of www.smartindianagriculture.in