The government’s decision to set up 12 such courts for legislators comes at a time when there are over 2.8 crore pending cases. Should they be given a special privilege here too?

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

The law, we have been told, is equal for all. But a decision of the government, following a directive from the Supreme Court, seems to suggest that the law can be applied differently to different people.

On December 12, the government informed a Supreme Court bench of Justices Ranjan Gogoi and Navin Sinha that it would set up 12 special courts to adjudicate on criminal cases pending against 1,581 Members of Parliament and those in legislative assemblies. These courts, to be set up at a cost of Rs 7.80 crore and made operational by March 1, 2018, would dispose of these cases, estimated to number around 13,680, within a year.

Two of these special courts would deal exclusively with cases filed against 228 MPs, while the remaining will be set up in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Karnataka, Kerala, MP, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Each of these 10 states has over 65 legislators facing criminal cases.

The centre’s proposal was made before the bench at a hearing in a PIL filed by advocate Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay.

LIFE BAN

The main issue raised in the PIL, as the bench itself noted during the course of the hearing, was to impose a life ban on convicted politicians contesting elections—a matter that the apex court will now hear on March 7. However, the centre proposed the setting up of these fast-track courts and the Supreme Court accepted it.

The decision has predictably not gone down well with politicians, especially those from the opposition parties who feel that an attempt is being made by the centre and the highest level of the judiciary to single out lawmakers as errant citizens.

But, against the larger canvas of Article 14, where one talks about the equality of all citizens, or the right of every prisoner to a fair and speedy trial, is this decision correct? Does it give one set of people a chance at a speedy trial while condemning others to years of legal battles?

HUGE PENDENCY

A perusal of various figures shows the colossal pendency in various courts of India and the uphill task facing common people. According to the National Judicial Data Grid, as of December 20, 2017, 8.71 percent of all cases in various courts have been pending closure for over 10 years, while 16.11 percent are pending for a period between five to 10 years. Nearly five percent of pending cases are against senior citizens, while 10.32 percent were filed by women.

The scenario only gets grimmer. According to data furnished by the ministry of law and justice before Parliament, the total pendency of cases in the Supreme Court as of July 14, 2017, stood at 48,772 civil cases and 9,666 criminal cases. However, a staggering 29.26 lakh civil cases and 10.88 lakh criminal cases were pending before various high courts in December 2016. It is worse in district and subordinate courts, where over 2.74 crore cases are pending. While it is true that the number of cases pending before the Supreme Court and various high courts have witnessed a marginal decline over the past few years, the pendency has been steadily increasing, going from 2.64 crore in 2014 to 2.70 crore a year later and 2.74 crore in 2016.

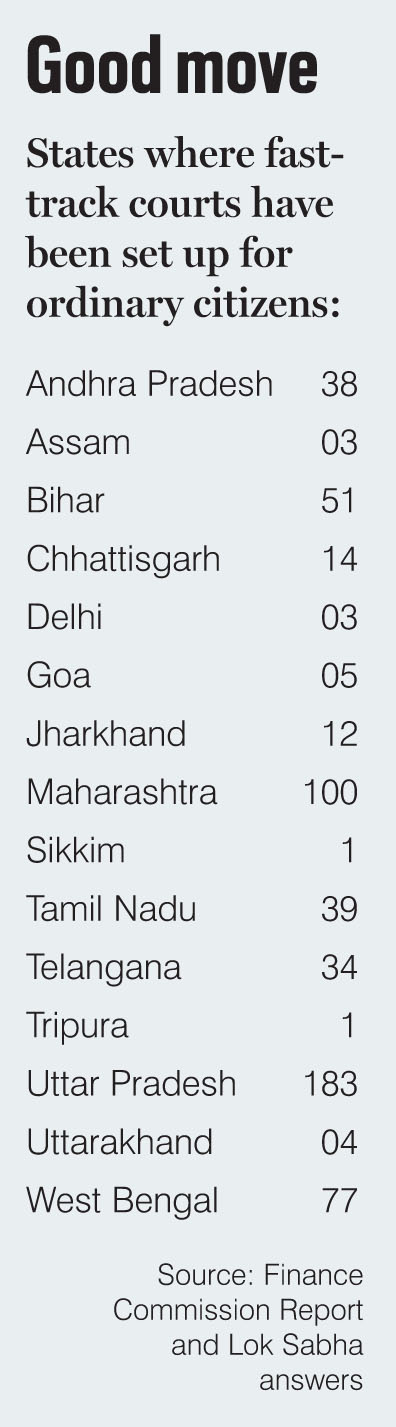

In fact, efforts by the government over the past three years to fast-track cases filed against common citizens have failed to yield results despite funds being allocated for it. According to recommendations made by the 14th Finance Commission, a staggering Rs 4,144.11 crore was allocated to state governments to set up 1,800 fast-track courts between 2015 and 2020. However, only 575 fast-track courts have so far been set up across the country. Sadly, states with a high prevalence of crime like Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala and Punjab have not set up even a single such court despite receiving huge allocations for the purpose.

RS PROTESTS

Why, then, is there a sudden urge to only fast-track cases involving lawmakers? A few days after this proposal, the Rajya Sabha witnessed vociferous protests against the move, mainly by opposition members. Union Finance Minister and Leader of the House in the Rajya Sabha Arun Jaitley backed the move, saying: “There is a sentiment in society where people do indulge in politician bashing… Can we say that we have a vested interest in ensuring that at least our cases are delayed or should at least it be in our interest that, like Caesar’s wife, we must be above suspicion? If an allegation is made, let it be tried expeditiously.”

As opposition MPs like the Congress’ Ghulam Nabi Azad and Anand Sharma, Samajwadi Party’s Naresh Agarwal and the Nationalist Congress Party’s Majeed Memon criticised Jaitley’s stand and accused him of politicising the issue, the BJP leader shot back: “You are a class apart because you are lawmakers… you must set the example.”

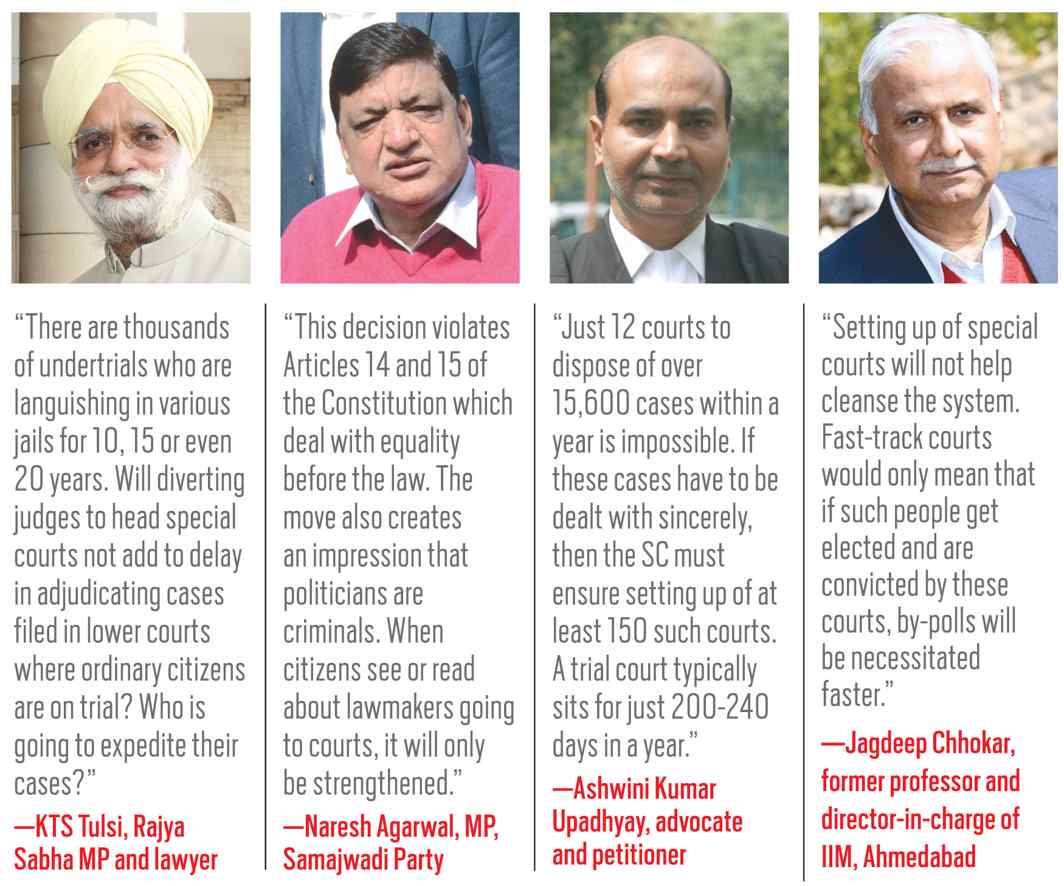

While Jaitley may take the moral high ground on this issue, why should the common man be denied speedy justice? Rajya Sabha MP and eminent lawyer KTS Tulsi feels that the decision to set up fast-track courts for MPs and MLAs is unfair. “There are thousands of undertrials who are languishing in various jails for 10, 15 or even 20 years. Will diverting judges to head special courts not add to delay in adjudicating cases filed in lower courts where ordinary citizens are on trial? Who is going to expedite their cases? Merely because they are poor, they cannot be confined to prisons indefinitely,” said Tulsi.

Agarwal told India Legal: “This decision is a blatant violation of Articles 14 and 15 of the Constitution which deal with equality before the law. The move creates an impression that politicians are criminals and when citizens see or read about lawmakers going to courts on a daily basis to stand trial, this imp-ression will get strengthened. The government isn’t setting up special courts to try terrorists or criminals accused in heinous offences, but it wants fast-track courts to try politicians…this is absurd.”

MOVE AGAINST OPPOSITION?

Some opposition leaders are also of the view that the decision to specifically fast-track cases of politicians could be a tool to harass leaders who are not part of the ruling dispensation, especially in cases that are being probed by central agencies like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

Some opposition leaders are also of the view that the decision to specifically fast-track cases of politicians could be a tool to harass leaders who are not part of the ruling dispensation, especially in cases that are being probed by central agencies like the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI).

A senior RJD leader told India Legal on condition of anonymity: “Politically motivated cases are a reality and we are seeing that in the case of our party chief (Lalu Prasad Yadav) and Tejashwi Yadav. The BJP has a proven record of misusing the CBI, Enforcement Directorate and other agencies to harass and frame opposition leaders. Once their cases are fast-tracked, these leaders can be tried and convicted in false cases before the 2019 elections, which would naturally help the BJP.”

The sheer volume of cases against 1,581 lawmakers that are to be dealt with by the proposed special courts within the span of a year also raises doubts about the quality of justice that will be dispensed.

Interestingly, the petitioner, Upadhyay, himself isn’t convinced that these courts will serve the desired purpose. “Just 12 courts to dispose of over 15,600 cases within a year is practically impossible. If these cases have to be dealt with sincerely, then the Supreme Court must ensure setting up of at least 150 such courts. A trial court typically sits for just 200-240 days in a year. Even if these fast-track courts operate round the year, including on holidays and Sundays, they will have to dispose of at least three cases per day to clear the entire backlog within the Supreme Court’s deadline. How will they ensure that the verdicts delivered are fair?” Upadhyay asks.

Another view against the setting up of these special courts is that if people with criminal cases pending against them win polls, then they will have to vacate the seat if convicted, thereby precipitating frequent by-polls. Jagdeep Chhokar, former professor and director-in-charge of the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, said: “Setting up of special courts to dispose of cases against lawmakers will not help cleanse the system. In every election, political parties are known to field people with criminal cases. Records show that in nearly every election, at least three candidates with criminal cases pending against them contest from any given constituency and one of them always wins. This is why we have so many people with criminal cases as our lawmakers. Fast-track courts would only mean that if such people get elected and are convicted by these special courts, then by-polls will be necessitated faster.”

Chhokar suggests that a better way out would be to ban politicians with criminal cases against them from contesting polls. “There could be three riders: the case should have been filed six months to a year before filing of nomination by candidates, the person should have been chargesheeted, and the charges against the person should be punishable with a jail term of two years or more.

“If such candidates are banned from contesting, the electoral system would automatically get cleansed and at no extra cost to the exchequer towards setting up of fast track courts, providing facilities for their operations, investigations, and so on.”

A point to ponder.