Above: Over 600 changes have now been made to tax rates of 1,300 goods and 500 services

At the launch of GST, Prime Minister Modi stated that it would bring economic unification through easier interstate movement of goods, simpler administration and lower tax rates. A year later, it is the most reviled tax in the country

~By Sanjiv Bhatia

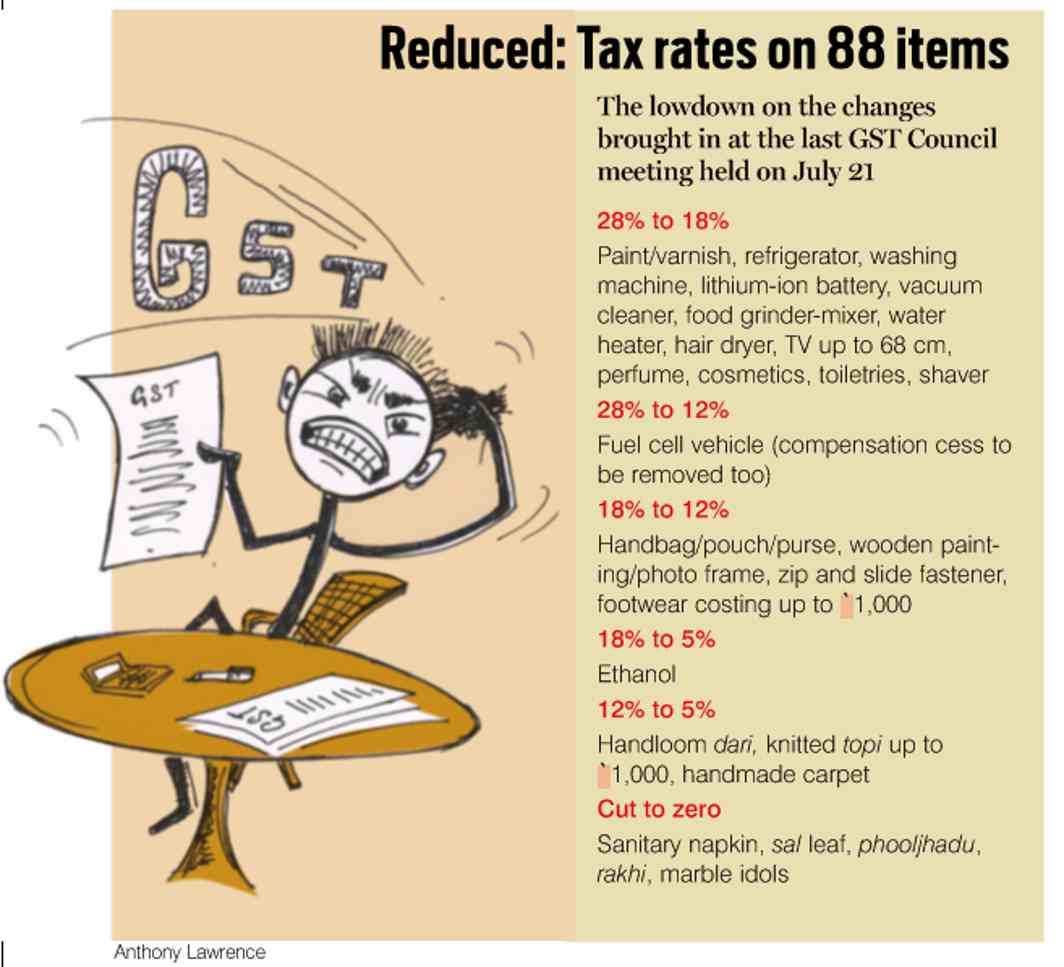

At the 28th meeting of the GST Council last week, tax rates on 88 items were cut. Rates on ethanol were reduced from 18 percent to five percent in an apparent bid to help the sugar industry; tax on lithium-ion batteries was cut from 28 percent to 18 percent to promote the electronic vehicle industry; taxes on rakhis and marble idols were cut to zero in anticipation of the upcoming holiday season.

This follows a pattern of over 600 changes that have now been made to rates, structure, frequency of filing, list of exempt products, and so on, since the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was implemented in July 2017. It’s hard to imagine how any tax policy can be useful with these frequent and capricious changes.

Businesses want consistency, especially in government policy. Unpredictability adds to the risk and the cost of doing business. The virtually daily changes to GST have added uncertainty and made it difficult for companies to focus on investment and expansion. It is no wonder that GST, which was intended to simplify indirect taxation and make it easier to do business, is so loathed by the very people it was designed to help.

GST, if implemented prudently, is a useful tax instrument. More than 160 countries use it, or its variant, the Value Added Tax (VAT), and so the principles that make it effective have already been laid out. There is a well-established body of evidence on how best to implement it, yet the Indian government decided to ignore that in favour of convoluted implementation of GST. Clearly, a combination of ignorance, hubris and politics was at play.

All taxes affect economic growth because they distort the efficient allocation of resources. The objective of a good tax policy is to minimise these distortions and maximise overall production in the economy. The least efficient form of taxation is one where the government subjectively alters consumer behaviour by favouring one sector or product over another through differential taxation. That is precisely what the government has done by choosing multiple tax slabs in GST and subjectively taxing products and services at different rates.

There are about 1,800 goods and services (1,300 goods and 500 services) under the ambit of GST. Each of these products has been slotted into one of five tax slabs—0%, 5%, 12%, 18% and 28%. The consequences of being taxed at 18% versus 5% can be enormous for the sale of a product. Entire industries can potentially be ruined through such capricious taxation. When frozen fish is exempt from taxation and frozen chicken gets taxed at 5%, it is clear that political discretion, and not economic logic, was used to rate these 1,800 items.

After a year, and 28 meetings of the GST Council, it appears that the implementation of GST is being driven primarily by political considerations and not tax efficiency or revenue maximisation. As an example, the original list of 226 items in the 28% tax slab has, over time, been whittled down to 35, primarily as a result of political interference and lobbying by special interest groups.

The present GST structure, with differential taxation, allows the government to control the final price of all goods and services in India. The consumption of products and the allocation of economic resources will inevitably shift towards industries with lower GST rates. Instead of the free market determining consumption and production decisions, the government and its bureaucracy now control the allocation of resources. This is a frightening thought.

Differential tax slabs enhance the government’s ability to choose which industries to favour through lower rates. Politics and vote-bank considerations determine which products get reduced GST rates. Instead of making progress towards less government, economic freedom and free-market policies, the country took a huge step back to the days of the Licence Raj when the government picked winners and losers.

Additionally, differential tax rates across products give extraordinary arbitration powers to the government’s Revenue Service. The same tax officials who have for years terrorised businesses with arbitrary tax demands are now in charge of deciding whether a rubber ball is a rubber product taxed at 5% or a sporting good taxed at 18%.

If all products and services were taxed at the same rate, there would be no room for ambiguity and political meddling. We know from the experience of other countries that the single biggest reason for a GST tax structure to fail is poor administration which invariably results from an overly complicated system. Multiple tax rates guarantee poor administration.

Ghana introduced GST in 1995 with three different rates but soon abandoned it since it became too complicated to implement. China had a similar experience, and it also eventually rejected multiple rates in favour of a simple policy with one single rate across all industries.

Studies conducted by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank found that the most effective way to structure a GST/VAT tax is to have a single rate across all products with zero rate (exemption) granted only to exports. This ensures simplicity and prevents one group from having an unfair advantage over another.

In fact, on June 30, 2017, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had himself said during the launch of GST in Parliament: “Just as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel unified India by helping several princely states subsume into a common entity, the GST will bring economic unification. If we take into consideration the 29 states, the seven Union Territories, the seven taxes of the Centre and the eight taxes of the states, and several different taxes for different commodities, the number of taxes sum up to a figure of 500! Today all those taxes will be shred off to have ONE NATION, ONE TAX right from Ganganagar to Itanagar and from Leh to Lakshadweep.” However, these promises seem to be water down the drain now.

The majority of countries (82 percent) who have introduced the GST/VAT-type tax apply a single rate structure, mainly because it is fair and easy to administer. The GST in New Zealand, widely regarded as the most efficient in the world, has a single standard rate of 12.5 percent across all industry groups. None of the 160 or so countries that use a GST-type tax has five different rate structures: India is the first.

Under the current GST, almost half the base is exempt from taxes. What was originally intended only for absolute necessities like food grains now includes an eclectic group like handicrafts, cotton for a Gandhi topi (but not all cotton), spacecraft, hearing aids, silkworms, and so on. While GST exemption may appear to be a well-intentioned attempt to provide tax relief to the poor, it needlessly complicates the administration of GST and adds materially to its costs. Over time, politics and lobbying by special interest groups will move more goods and services into the exempt category, resulting in lower revenues and further distortions in rates across industries.

Exemptions violate the very intent of an indirect tax like GST which is designed to broaden the tax base and get into the tax net people who work in India’s informal sector where direct taxation is difficult. Instead of exemptions, the government should provide a direct payment to each low-income family as relief from the GST tax. So, for example, if the uniform GST rate on all products and services is 10%, then each family making below a threshold amount of Rs 10,000 per month would get a direct payment of Rs 1,000 to compensate for their tax expenditure. This would be a more neutral and less distortive way of providing tax relief to the poor than arbitrarily exempting entire categories from tax. GST can be made significantly simpler by applying it equally to all goods and services, without any exemptions.

It is perplexing why the Indian government chose to start with such a complex GST structure. It would have made more sense to start simple, and then add bells and whistles once the policy and technology bugs got ironed out. But GST, in its current form, has been complicated to the point that its administration and compliance have created chaos and resentment. When the costs to administer and comply far exceed the benefits from GST, it will create doubts regarding its value.

In the World Bank ranking on ease-of-paying taxes, India ranks near the bottom—172 among 190 countries. India also ranks at the very bottom in the percentage of voters who pay taxes—less than 7%—lowest among major economies. This suggests a direct correlation between simplicity and tax compliance that our policymakers are missing. The simpler the tax policy, the higher the compliance. When people find it easier to follow tax regulations, they are more likely to comply with them. Instead of cockamamie schemes like demonetisation, the government should consider tax simplification to reduce tax evasion and black money.

Famous painter Hans Hofmann once said: “The ability to simplify means to eliminate the unnecessary so that the necessary may speak.” This applies equally to effective tax policy as to good art. Good tax policy has the following ingredients: it is (a) broad-based (b) proportional (c) simple and predictable (d) easy to monitor to minimise cheating (e) neutral in that it does not unfairly advantage one sector or group over another and (f) easy to implement.

A single rate across all industries, with no exemptions, and a single source for administration, collection and refunds will go a long way in making the GST the “game-changer” it was intended to be. Otherwise, it could well turn out to be another tax boondoggle that increases tax terrorism, hikes administration and compliance costs, and hampers investment and growth.

—The writer is a financial economist and founder of contractwithindia.com

Comments are closed.