Above: Ancient and medieval Indian texts have extolled the virtues of the Cannabis indica and sativa plants

Over the past four years, support for de-criminalising cannabis has come from various lawmakers, be it for medicinal use or recreational. But this could also open the floodgates for drug cartels

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

Cannabis, hemp, pot, ganja, bhang—call it what you wish, but there’s no denying that the venerable, yet also reviled, marijuana plant has been endemic to the Indian subcontinent and the use of its derivatives as medicine or recreational drugs is common among spiritual (particularly Shaivites) and ordinary folk alike.

The first mentions of its sanctity and use appear in the Atharva Veda, compiled around 1200-1000 BCE, where cannabis is described as “one of the five most sacred plants on earth” and a “reliever of anxiety”. Subsequent, Indian scriptures like the Sushruta Samhita (6 BCE) rave about its medicinal uses.

Yet today, as the world is waking up to the potential of exploiting cannabis for medicinal use and accepting the rationality behind making marijuana a legal recreational drug, the five-bladed leaf remains a banned substance under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985. Incidentally, Canada recently became the first G7 country to legalise the recreational use of cannabis.

In a recent article for web portal The Print, Congress MP from Thiruvananthapuram, Shashi Tharoor, argued for legalisation of marijuana in India, “the land of bhang”. In the article co-authored by his nephew Avinash Tharoor, an officer with UK-based drugs charity Release, Tharoor says that “prohibition of cannabis was first entrenched in Indian law in 1985, with the introduction of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act. However, the drug had already been illegal in the country for over two decades because our government had signed the United Nation’s Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs treaty in 1961”.

Over the past four years, support for de-criminalising cannabis use has come from lawmakers cutting across party lines. Union minister for women and child development, Maneka Gandhi, had in July 2017 at a meeting of a group of ministers (GoM) headed by Rajnath Singh, proposed legalising marijuana for medicinal use. The GoM was examining the draft National Drug Demand Reduction Policy.

Tathagata Satpathy, senior Biju Janata Dal MP who admits to being a pot user once, has also backed legalising marijuana. He stated that the cannabis ban is “elitist” and was “imposed because ganja was the intoxicant of the poor”. Dharamvir Gandhi, a cardiologist and Lok Sabha MP from Patiala in Punjab, a state infamous for its drug addiction (mostly opioids), had, in November 2017, moved a Private Members Bill in Parliament seeking amendments to the NDPS Act for legalising marijuana.

In stark contrast, the advocates of a ban on cannabis and any of its derivatives argue that though pot and hashish may be “soft drugs” with less harms than opioids, psychotropic substances or even cigarettes and alcohol, they lead the user to graduate to “hard drugs” in the medium to long term. This “gateway drugs” theory, however, is being increasingly disproved, or at least disregarded, by the medical fraternity worldwide. (See interview with Dr Atul Ambekar)

The NDPS Act, under Section 2, criminalizes cannabis use under the classifications of charas (the separated resin of cannabis), hashish oil, ganja (the flowering or fruiting tops of the cannabis plant) or any mixture, with or without any neutral material, of charas, hashish oil or ganja. The Act also bans cultivation of cannabis and “manufactured drugs” made from “medicinal cannabis” (any extract or tincture of hemp).

“De-criminalise use of cannabis”

DR ATUL AMBEKAR, professor, National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre and Department of Psychiatry, AIIMS, tells PUNEET NICHOLAS YADAV that making cannabis legally available would facilitate medical research and lead to excellent medicines being formulated. He was also the lead researcher for Punjab Opioid Dependence Survey 2016.

DR ATUL AMBEKAR, professor, National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre and Department of Psychiatry, AIIMS, tells PUNEET NICHOLAS YADAV that making cannabis legally available would facilitate medical research and lead to excellent medicines being formulated. He was also the lead researcher for Punjab Opioid Dependence Survey 2016.

What are your views on the demand for legalisation of marijuana in India?

Cannabis is an indigenous plant in India and its use is ingrained in the culture of many parts of the country. Among the various products of the plant, bhang continues to be legal and its sale is regulated by various states. Other products such as ganja and charas are illegal. There may be a concern that if all the products are legalised, it may increase the number of people using cannabis. However, continued criminalisation of cannabis use is harmful for society as it enhances the risk of charas and ganja users getting exposed to more addictive drugs like heroin. Thus, there is merit in the argument that policy reforms be considered for cannabis in India. As a first step, we should consider “de-criminalisation”, i.e., not prosecuting those who merely use or consume cannabis products. Gradually, after reviewing the impact of such a policy move, we can decide whether to legalise or not.

What is the extent of cannabis addiction in India compared to other hard drugs like opioids or chemical-based narcotics?

Existing estimates (from a 2001 survey) suggest that among men, three percent use a cannabis product (bhang/charas/ ganja). This is higher than the estimates for opioids (which was 0.7 percent), but much lower than the five percent globally who uses cannabis, as per UN estimates.

You are part of a team that has been working on a national survey on drug addiction since 2016. The last such survey was carried out in 2001. When is the next survey expected?

Currently, the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment is conducting a national survey (with technical help from AIIMS). The report is likely to be available later this year.

How serious is the government about dealing with drug abuse?

In India, elaborate mechanisms exist for “Drug Supply Reduction” (by law enforcement agencies such as the Narcotics Control Bureau and others). For another aspect of drug control, “Drug Demand Reduction”, our response needs to be scaled up. Two ministries are primarily involved in this issue—Social Justice and Empowerment (works through NGOs) and Health and Family Welfare (works through government hospitals). The number of treatment facilities is grossly low compared to the need for them. Hence, continued efforts are needed to enhance the availability of treatment facilities, including having trained human resources and infrastructure.

Many countries are now legalising cannabis for medical and recreational use. Is this a right move?

Yes, many countries have realised the limitations of the “Supply Control-oriented” approaches and hence are undertaking policy reforms. One hopes that India also thinks logically on the basis of scientific evidence to formulate its policies as opposed to those based on notions of morality.

Is there any basis for the argument that making marijuana legal for medical use would help in research for developing new drugs for treating chronic pain, fibromyalgia, some types of cancers, etc?

There is a growing interest across the world in research on the medical potential of cannabis derivatives or synthetic products. Legal availability of these products would certainly facilitate more research and it could lead to excellent medicines being formulated from cannabis.

Is there any evidence that making marijuana legal would help combat drug addiction? Some people argue that marijuana and hashish are soft drugs and have fewer ill effects compared to opioids like smack, cocaine and chemical narcotics. Making it legal would also bring down its price and give addicts of hard drugs a cheaper and less harmful alternative. Can addicts of opioids or other drugs switch to cannabis derivatives if given the option?

Research conducted the world over suggests that many of those who use harder/more addictive drugs like cocaine or heroin, may have started drug use with cannabis. On the other hand, the vast majority of those who use cannabis do not shift to other drugs. In other words, the so-called “gateway theory” (that using cannabis can lead to more harmful drugs) has no strong scientific evidence today. Considering the relative harms and addictive potential of cannabis or opioids/cocaine, there is evidence which calls for a graded policy approach. In other words, for more harmful drugs such as heroin or cocaine, policies need to more stringent, while for less harmful substance like cannabis, it needs to be less strict. However, once people develop an addiction to other drugs like cocaine or heroin, it is difficult for them to switch to cannabis without treatment or professional help. Thus, easier availability of cannabis would certainly be helpful for those who have not yet started other drugs such as heroin /cocaine, but it will not help those who have already developed an addiction to these harder drugs.

However, the Act allows the exploitation of cannabis as bhang since it excludes the categorisation of cannabis leaves and seeds as narcotic substances. Bhang is typically made by grinding cannabis leaves and seeds and mixing it with milk (though the clandestine use of the plant’s flowering tops—a banned substance—in making this mixture is not uncommon). It is consumed in copious quantities by revellers, particularly during Holi and Mahashivratri celebrations, and is the accepted offering for Lord Shiva.

This apparent loophole in the NDPS Act has led to a paradox—cultivation of cannabis is illegal, but consuming bhang made from it isn’t. Several Indian states have government-run or sanctioned shops for sale of bhang, and cannabis leaves needed for making it are never in short supply.

Besides, bhang, hemp is also used widely in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand as a vegetable that is typically cooked on all special occasions, including weddings. Fibre from the cannabis plant can also be used for weaving garments—Satpathy had famously turned up in Parliament a few years ago dressed in a hemp kurta—and for manufacturing parchment. Hashish oil and other cannabis derivatives have also been commonly used in alternative medicine systems like Ayurveda and Unani for centuries.

In nearly all of India’s pilgrim towns known for their Shiva temples— including Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency of Varanasi— devotees consuming bhang and babas openly smoking a ganja/charas chillum is a common sight. If you post pictures of Himachal’s Parvati Valley on Instagram with hashtags like “Malana”, “Challal”, “chillum” or “stoned in Parvati”, there’s every possibility of receiving a message from someone who wants to sell you the “maal” (ganja or hashish).

Evidently, the criminalisation of cannabis cultivation hasn’t ended the wide availability of the plant from Kashmir, Uttarakhand and Himachal in the north to Kerala in the south and in most north-eastern states.

“Establish a medical cannabis plan”

SHASHI THAROOR, Congress MP from Thiruvananthapuram, recently advocated for the legalisation of marijuana in India. He tells PUNEET NICHOLAS YADAV why cannabis, a plant indigenous to India and whose derivatives like ganja, hashish and bhang have been used by people for centuries, should be made legal to enable its exploitation for medical use and curb its trafficking by drug cartels.

SHASHI THAROOR, Congress MP from Thiruvananthapuram, recently advocated for the legalisation of marijuana in India. He tells PUNEET NICHOLAS YADAV why cannabis, a plant indigenous to India and whose derivatives like ganja, hashish and bhang have been used by people for centuries, should be made legal to enable its exploitation for medical use and curb its trafficking by drug cartels.

Not many politicians would endorse a potentially controversial demand for legalising marijuana. What made you voice your support?

I have never hesitated to support a good cause when it will expand the freedoms of the people of India. My positions on Section 377, on the sedition law, on domestic workers’ rights and other issues have also been “potentially controversial”. If we shirk from confronting hard questions in the interests of avoiding controversy, we do our democracy a disservice.

Most countries which have legalised marijuana make a distinction between recreational and medicinal use of it. Should the government consider legalising marijuana for both these purposes or for medicinal use first?

It is important to distinguish between both uses of the substance. There is vast evidence that medical cannabis and its derivatives can alleviate various ailments, including those of multiple sclerosis, epilepsy and the side-effects of chemotherapy. It is vital that this drug be made available to patients easily, affordably and as soon as possible. We should establish a government-run medical cannabis programme, as other countries have, so that this drug can be prescribed to and used by patients.

The last national survey on drug abuse conducted by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime was in 2000-2001. It estimated that 732 lakhs used alcohol and drugs, of which 87 lakhs were cannabis users. Thereafter, no national survey on drug abuse was conducted. Is the government really serious about tackling it?

Perhaps the greatest crisis faced by India regarding drugs relates to the harm and deaths caused by heroin and other opioids in Punjab. While causing immeasurable harm to individuals, particularly those in poor communities, the trade of these drugs is taking place across the border and may be funding terrorist groups. It is vital for the government to take this issue seriously. Alongside combating cartels and militant groups on the border, we must provide treatment to people in Punjab who are dependent on these drugs. Arguably, governments have not taken this issue seriously, but the national security implications ought to make them wake up and pay attention.

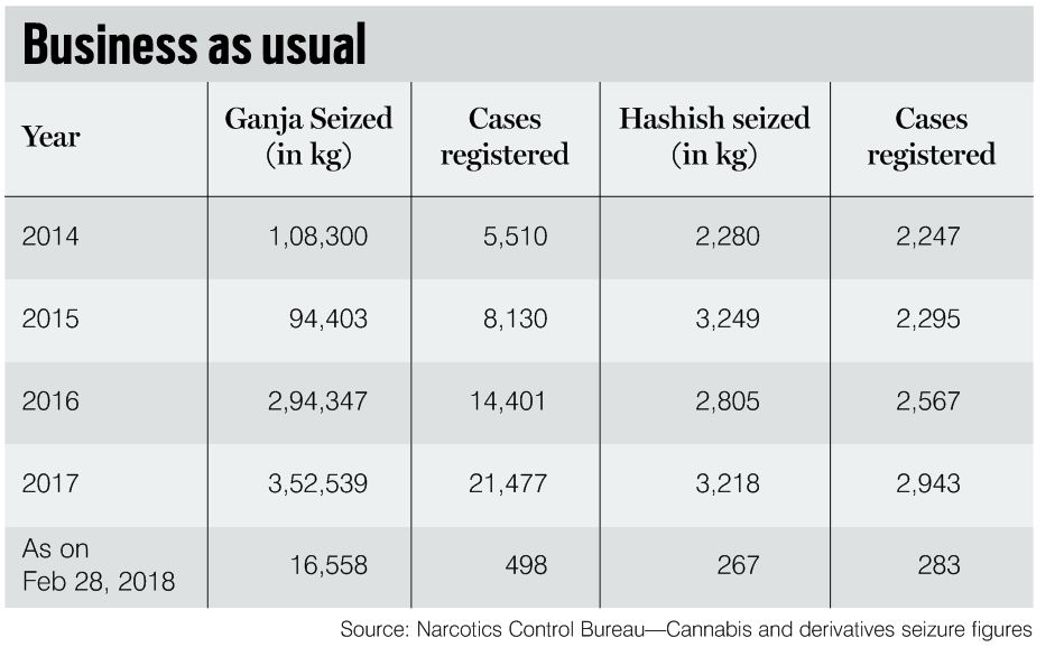

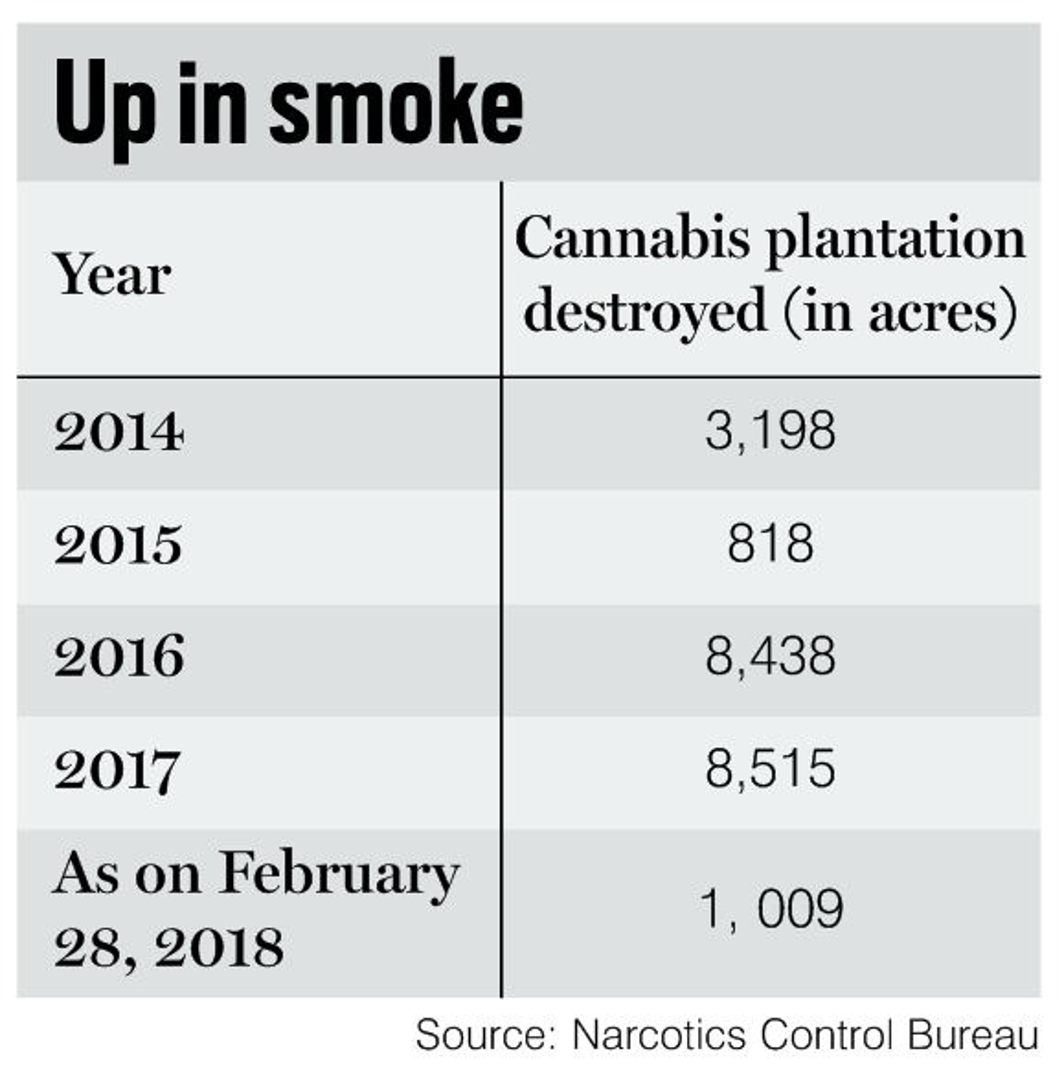

The Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) and other enforcement agencies are mandated to destroy cannabis cultivation, seize marijuana or its derivatives from anyone found in their possession and book him/her under relevant sections of the NDPS Act. A cursory glance at data accessed by India Legal from NCB on seizure of ganja and hashish (the two main derivatives of cannabis used as soft drugs) and destruction of the marijuana crop is enough to prove that efforts to curb circulation of hemp have not yielded the desired results—even over three decades after the enactment of the NDPS Act. (See boxes)

Instead, the ban has triggered a massive shadow economy for cannabis cultivation and trafficking. In Amsterdam, for instance, where recreational use of marijuana and its derivatives is legal, Malana Cream (made from cannabis in and around Malana village of Himachal)—is among the top-selling hashish on bar and pub menus. It could fetch a price of over $250 for the standard measure of a little over 10 grams (a tola in Indian parlance). Obviously, Indian cannabis is not only being circulated within the country but also being smuggled abroad. Someone in the enforcement agencies isn’t doing their job.

In an exclusive interview to India Legal, Tharoor said that legalising cannabis in India would check trafficking of marijuana and also help the country benefit financially from the legitimate trade of cannabis. “Everyone involved in the illegal cannabis trade—from its cultivation, to its processing, transportation, distribution—relies on either corrupting or avoiding authorities. By prohibiting cannabis, we are gifting the drug’s trade to cartels, and thereby, unintentionally fuelling corruption… Establishing a regulated market will create a cohort of people working legitimately with or in the cannabis industry who do not need to corrupt the authorities, or to be corrupted themselves,” Tharoor said.

In an exclusive interview to India Legal, Tharoor said that legalising cannabis in India would check trafficking of marijuana and also help the country benefit financially from the legitimate trade of cannabis. “Everyone involved in the illegal cannabis trade—from its cultivation, to its processing, transportation, distribution—relies on either corrupting or avoiding authorities. By prohibiting cannabis, we are gifting the drug’s trade to cartels, and thereby, unintentionally fuelling corruption… Establishing a regulated market will create a cohort of people working legitimately with or in the cannabis industry who do not need to corrupt the authorities, or to be corrupted themselves,” Tharoor said.

He added: “While we may not be able to fully eradicate the illegal trade, legalisation will help legitimate groups and the state capture some of the revenue that is currently going into the pockets of organised crime. With effective regulation, it can also help empower rural farmers… Drug cartels do not want cannabis to be legalised as they rely on prohibition to sustain their business model.”

Dharamvir Gandhi, while agreeing with Tharoor, believes that the cannabis ban also helps India’s powerful tobacco and liquor lobby. “It is now widely accepted that ganja has fewer harms than tobacco and alcohol and the addiction is not even close to that for opioids. Yet, while the government allows the tobacco and liquor industry to thrive, cannabis is banned. If legalised, cannabis would eat into the market for cigarettes and alcohol, and will perhaps even be a cheaper and certainly less harmful substitute,” Gandhi told India Legal.

But by advocating for legalisation of cannabis, aren’t these lawmakers condoning the proliferation of a narcotic substance that can lead to serious mental health issues? Tharoor disagrees. “The legalisation of cannabis is absolutely not about condoning its use. Our government and previous governments rightly warn of the harmfulness of tobacco use—but we don’t prohibit cigarettes because we know that the best way to control a drug is by ensuring the state regulates its production and supply. If part of the tax revenue earned from the cannabis trade is allocated for education programmes that ensure that young people are aware of the risks associated with drug use, I will support it. When someone buys cigarettes today in India, the packet comes with a warning of the harmful effects of tobacco. A bag of cannabis comes with no such warning as illegal suppliers have no incentive to provide such information,” Tharoor told India Legal.

Despite the arguments that advocates of cannabis legalisation make to support their cause, not all are convinced. Ravi Mantha, who describes himself as a health guru and holistic healer, had in his critique of Tharoor’s article in The Print raised a valid point by stating: “Many states in the USA have already legalised marijuana, and it will suit us to wait a generation to see the effect it has on those societies before we do the same.”

A Narcotics Control Bureau official told India Legal on condition of anonymity: “What people like Tharoor are saying may have some merit, but the fact is that Indian ganja and hashish have a huge market not only domestically, but also abroad. Legalising cannabis will open the flood gates for drug cartels operating abroad to exploit the relaxation in India.”

US states which have legalised marijuana either for medicinal or recreational use—or both—over the past few years are beginning to realise the flip side of the move now. Although legalisation has led to windfall gains for American states like California, Colorado and Washington, an NBC report earlier this year said that an unintentional fallout has been that these states were also “providing cover for transnational criminal organisations willing to invest big money to buy or rent property” where they “home grow” cannabis for trafficking. According to US government estimates for the last financial year, California earned annual revenue of $2.75 billion for sale of legal marijuana, both medicinal and recreational, while the figure stood at a staggering $1.56 billion for Colorado and $1 billion for Washington.

The NBC report, quoting US federal and local officials, said: “Chinese, Cuban and Mexican drug rings have purchased or rented hundreds of homes (for growing cannabis) and use human trafficking to bring inexperienced growers to the United States to tend them.”

Arguments for and against legalisation of cannabis seem equally compelling. Whether the likes of Tharoor, Dharamvir and Maneka Gandhi and Satpathy will be able to force the government to rethink its ban on cannabis is anyone’s guess. However, the debate on whether India—the land of bhang—should lift prohibition on marijuana is certainly an intoxicating one.