Illustration: Anthony Lawrence

At a mind-blowing Rs 10 lakh crore approximately, Non-Performing Assets are not just about individuals and corporations defaulting on payments they owe but is part of a more complex self-serving exercise that makes a mockery of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, introduced in 2016

~By Sujit Bhar

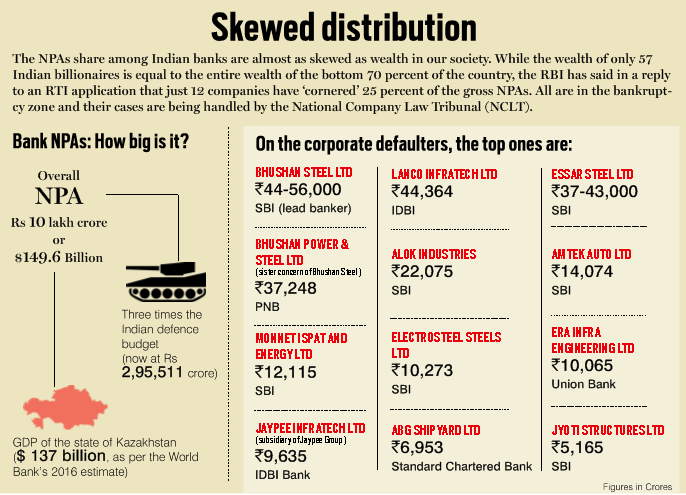

Deep financial scams are not new to India. They range from fodder scams to the notional 2G scams and illegal mining operations. However, the issue of non-performing assets (NPA) in banks has become a huge albatross hanging from the neck of the NDA government. Initial estimates peg the NPA figure at an astonishing Rs 10 lakh crore, more than the GDP of some countries and certainly more than the annual budgets of most states in India.

However, what is of greater concern is that NPAs are not just to do with bad business decisions or the propensity of some promoters to decamp with public monies, but, as it turns out, there is another method to this madness. It becomes clear when the reconstruction of the company, through the new National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) yields a new “buyer” that bids for higher gains. Within such bidding consortia—if checked for facts—will often be found the original promoter, who had refused to pay his dues in the first place. His return to legality can be sanctified through loopholes that exist within legislations, even after amendments.

Worked in flashback style, one can start at May 19, when Tata Steel announced its acquisition of Bhushan Steel Ltd (BSL), a debt-laden steel major against whom insolvency proceedings had been initiated under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), last year. While the Tatas’ Rs 32,500 crore bid, accepted by the NCLT, gave the company a notional controlling stake of 72.65 per cent in BSL, they were to soon discover that controlling stake did not necessary mean they were in control. When company officials wanted to assert their presence at BSL’s Dhenkanal plant in Odisha, there was resistance from people loyal to the original promoters. This has, in turn, been causing problems in the complete takeover, forcing the Tatas to lodge a complaint with the NCLT.

Code Amendment – 29A

The Insolvency And Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Act, 2017

“29A. A person shall not be eligible to submit a resolution plan, if such person, or any other person acting jointly or in concert with such person—

- is an undischarged insolvent;

- is a wilful defaulter in accordance with the guidelines of the Reserve Bank of India issued under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949;

- has an account, or an account of a corporate debtor under the management or control of such person or of whom such person is a promoter, classified as non-performing asset in accordance with the guidelines of the Reserve Bank of India issued under the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and at least a period of one year has lapsed from the date of such classification till the date of commencement of the corporate insolvency resolution process of the corporate debtor: Provided that the person shall be eligible to submit a resolution plan if such person makes payment of all overdue amounts with interest thereon and charges relating to non-performing asset accounts before submission of resolution plan;

- has been convicted for any offence punishable with imprisonment for two years or more;

- is disqualified to act as a director under the Companies Act, 2013;

- is prohibited by the Securities and Exchange Board of India from trading in securities or accessing the securities markets;

- has been a promoter or in the management or control of a corporate debtor in which a preferential transaction, undervalued transaction, extortionate credit transaction or fraudulent transaction has taken place and in respect of which an order has been made by the Adjudicating Authority under this Code;

- has executed an enforceable guarantee in favour of a creditor in respect of a corporate debtor against which an application for insolvency resolution made by such creditor has been admitted under this Code;

- has been subject to any disability, corresponding to clauses (a) to (h), under any law in a jurisdiction outside India; or

- has a connected person not eligible under clauses (a) to (i).

Explanation.—For the purposes of this clause, the expression “connected person” means—

(i) any person who is the promoter or in the management or control of the resolution applicant; or

(ii) any person who shall be the promoter or in management or control of the business of the corporate debtor during the implementation of the resolution plan; or

(iii) the holding company, subsidiary company, associate company or related party of a person referred to in clauses (i) and (ii)…

To understand why this was happening, one needs to take a look at the larger picture. Bhushan Steel is one of the hundreds of companies which took thousands of crores in loans and then failed to pay back. An NPA on any financial platform is a symptom of a bigger, hidden malaise. When the malignancy grows to be a Vijay Mallya or a Nirav Modi who flee the country, the disease is beyond treatment and legal and criminal processes have to be initiated to save connected assets and stakeholders. However, it was thought that the disease was still treatable when the government two years ago brought in the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code which was to have provided a logical exit route. It was allied to the accounting processes that identified and set aside unpaid dues as NPA.

The innovative approaches of Indian promoters have brought the inadequacies of the Code to the fore, with illegitimate activity, and not just bad business decisions or a bad market environment having destroyed the business. Promoters who have huge unpaid dues to their names are returning to try and reclaim their companies, presenting a different “front” or a conglomerate of investors with a name that is technically acceptable to the bankers or insolvency experts. In the process, they want to pay a pittance to regain control, forgetting the massive NPA.

The issue had become so big that the government brought in an ordinance to amend the Code and specifically deny such promoters—who are wilful defaulters—a return route. The amendment too (it has been formally incorporated into the Code by parliament), it seems, has fallen short. The ordinance was promulgated late last year and Section 29A was added to the Code. The relevant portion says: “A person shall not be eligible to submit a resolution plan if such person, or any other person acting jointly with such person, or any person who is a promoter or in the management control of such person, is an undischarged insolvent.” It also makes sister concerns and corporate guarantors ineligible to bid for these companies.

However, there are legitimate windows open, still, for the original promoters. They have to pay back the dues, in which case the NPAs are transformed into standard assets. This the defaulting promoters would not do, because in not paying the dues in the first place, they had clearly shown their intention to reroute massive funds into their pockets (mostly offshore accounts).

How it works

These scams are well-planned. According to a senior official of a security establishment, who remains anonymous, “these are pre-conceived, meticulously planned, with active participation from bank officials, and even external auditors.”

How does this work? “It starts from the blueprint stage. For example, each item of machinery to be purchased—imported, or from domestic markets—is over-invoiced. In this age of internet connectivity, it is easy to cross-check the actual price of an item even in a foreign market, but due diligence is never carried out, not even by auditors later.

If, for example, a range of machinery costs Rs 1,000 crore, the invoices raised will be to the tune of Rs 3,000 crore, and tenders floated will receive replies from interested parties abroad who will be willing to deliver the right price, with a kickback. The bank consortia in India takes a cut (bribe) from the proceeds and a huge amount is transferred abroad. Hence, from the very beginning, Rs 2,000 crore would be quickly siphoned off by the promoters.”

How does that affect business? It will be a double delight for the promoter. “With over-invoicing, the net worth of the company, right from the word go, will be grossly overstated. Hence, when the bank loans money to the company based on such an inflated asset value, the loans will be higher. The entire premise of the loan is based on lies,” he said.

“Think of Vikram Kothari and Rahul Kothari, of Rotomac Global Pvt Ltd, makers of pens,” he said. “How much capital infusion do you think is needed to make ball point (or even gel) pens?” According to the CBI’s transit remand copy of February 2018, the complaint was filed by Brijesh Kumar Singh, Deputy General Manager/Regional Manager Bank of Baroda, Regional office Kanpur. The document says that the promoters had “cheated” Bank of Baroda of Rs 456.63 crore, and also “not repaid loan amount to six other banks (to the tune of) Rs 2,919.39 crore.”

“The very fact that such a huge amount was given as loan by the banks (six of them) for a pen factory is indicative of the rot within the system,” he said. “The net asset value of the entire operation could not have been anywhere near that figure.” he added.

Lawyer Devender Ganda says: “Think of the monies loaned (through Letters of Understandings) to diamond merchant Nirav Modi. What was the collateral offered, when all Modi has are rented shops? Most of Modi’s assets are beyond the borders of India. Under which law would Indian banks reclaim Modi’s assets that are beyond the jurisdiction of Indian courts?”

“The system is rotten. There is no accountability anywhere, no fear of law.” says a India Legal source.

That’s the Indian way.

When the NCLT accepts an insolvency petition, the return routes narrow down. And that is when the reverse bidding process (a backdoor entry) begins. The ordinance wanted to address this part, but the new Section 29A (see box) actually details cases in which the promoter may not be allowed to return. If it had detailed the parameters only through which a return would have been possible, the loophole could possibly have been capped. “There will always be loopholes in laws,” senior corporate lawyer Vidender Ganda told India Legal. “The government has been trying to seal the gaps, but a return route for promoters has not really been denied.”

The BSL case is a classic example of why the Code has failed to tame Indian promoters. BSL had been declared a stressed asset with unpaid dues amounting to Rs 56,000 crore and Tata Steel won the bid in an insolvency auction. But when the bidding process was still on, BSL promoter Neeraj Singal had said that promoters put their lives into building a company, meaning that their rights remain immutable. The law and the markets would disagree. But the Tatas’ first move to take control of the newly acquired plant was met with stiff resistance. Hence the Tatas complained.

The objective of the Singals was to wait for the outcome of another similar case where the promoters are trying to wrest back control despite huge unpaid dues. That complicated backdoor entry is being attempted by the Essar Group, promoters of Essar Steel, which collectively owes various banks upwards of Rs 43,000 crore. Recently Essar sold its refinery business to Russian oil giant Rosneft. Though Essar retains the distribution network, it is a relatively small business. However, during his prolonged negotiations for the deal, the Ruia brothers of Essar developed very good contacts with Russian business interests which they used to good effect. Steel had been Essar’s core competency, till the company spread itself thin and the world steel market plummeted. The NCLT has been looking into proposals from ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steel maker, the Tatas and even Vedanta. Of these, ArcelorMittal, who don’t have a plant in India, looked the best bet.

However, the Ruias seem determined to get back what they think is theirs. It is being said that a consortium of Russian bank VTB and Hong Kong-based SSG Capital Management is being formed to present a bid and the Ruias would have a small stake in that consortium. That is because despite the amendment to the code, the door has been left slightly ajar for a promoter to return, should he so desire. All eyes are now on how the offer from the consortium will be entertained by the NCLT or the courts. “If somebody can weave around the ten-odd disqualifications mentioned in the amendment (see box) then he/she can be back,” senior Ganda told India Legal. “These are early days of the Code as well as the amendment—approximately 270 days. The authorities have not been able to put in a proper administration yet and there will be changes initiated as experience grows.”

Technically, if the consortium’s bid succeeds, then it could agree to hand over operational control to the Ruias—who took massive loans in the name of the company and did not bother to pay back. That means that technically, while around Rs 43,000 crore will remain unrealised by the banks, the Ruias would have the company back by investing a much lower amount in the consortium. There could be no greater irony than the consortium getting an AA rating. By association, the Ruias too would gain in rating and the banks would then have no problem advancing more loans to them.

Then there is the case of JSW and the Jindals, wanting to take control of the bankrupt Monnet Ispat. Within this, another issue has come to the fore. It is the Code amendment’s “connected people” section. In the second week of May, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) cleared JSW Steel’s (a consortium led by it) bid for the company, saying there were no competition issues that could hinder the takeover. But the tweak in the ordinance, which says that backdoor entrants would be clubbed under the definition of “connected people”, has come into the picture and it is being alleged that Jindal is trying to get hold of Monnet through the back door. Sajjan Jindal, chairman JSW Group, has said that Section 29A-c shows the “immaturity” of the new bankruptcy laws and expects it to be dropped, but there has been criticism that this is a backdoor entry as Jindal’s sister Seema is married to Monnet Ispat’s current promoter Sandeep Jajodia.

While the above are some of the big boys of the Indian corporate world, smaller players have always bought back into their own, asset-stripped companies. With promoter shareholding of listed companies sometimes shooting up beyond the statutory 75 percent, there remain several options for him/her to raise further funds without diluting shareholding.

One such is deep debt, either by pledging shares to banks or restructuring outstanding loans. The buy-back costs far less for the promoter (than paying back dues) and a pliable bank can easily shift dues as NPAs and renegotiate with the same promoter.

The Modi government says it is determined to break this unholy alliance, but for that to happen, it will take more than the IBC in its current form to prevent what is actually the biggest scam happening in India, mostly on legal footing.