Above: Patents can have a dramatic impact on access to medicines when they are used to prevent competition/Photo courtesy: fhcindia.com

Patentees and licencees flout rules by deliberately evading critical information on a patent’s commercial working while applying for trademarks, but hardly any action is taken by authorities

~By Lilly Paul

In March 2012, Indian drug firm Natco Pharma was granted the first ever compulsory licence for the production of Nexavar, a drug used to treat liver and kidney cancer. The licence was granted on two grounds—availability and affordability. While a month’s supply of the original medicine from Germany’s Bayer Corporation cost around Rs 2.8 lakh, Natco Pharma made it accessible to all by ensuring a similar supply for approximately Rs 9,000. The licence was granted on the condition that Natco Pharma provides a quarterly account of sales to the authorities. However, a query raised before the Controller General of Patents, Designs, Trademarks and Geographical Indications (CG) revealed that no such details were available.

In India, patent infringements are the rule rather than the exception and seldom anyone files a case highlighting the defects in the granting of patents and trademarks. But that is precisely what Professor Shamnad Basheer, a legal academician, did in 2015 when he filed a writ petition in the Delhi High Court against defaulting patentees and licencees, who do not furnish information about the patent’s commercial working. He also blamed the Indian Patent Office for not taking action against them.

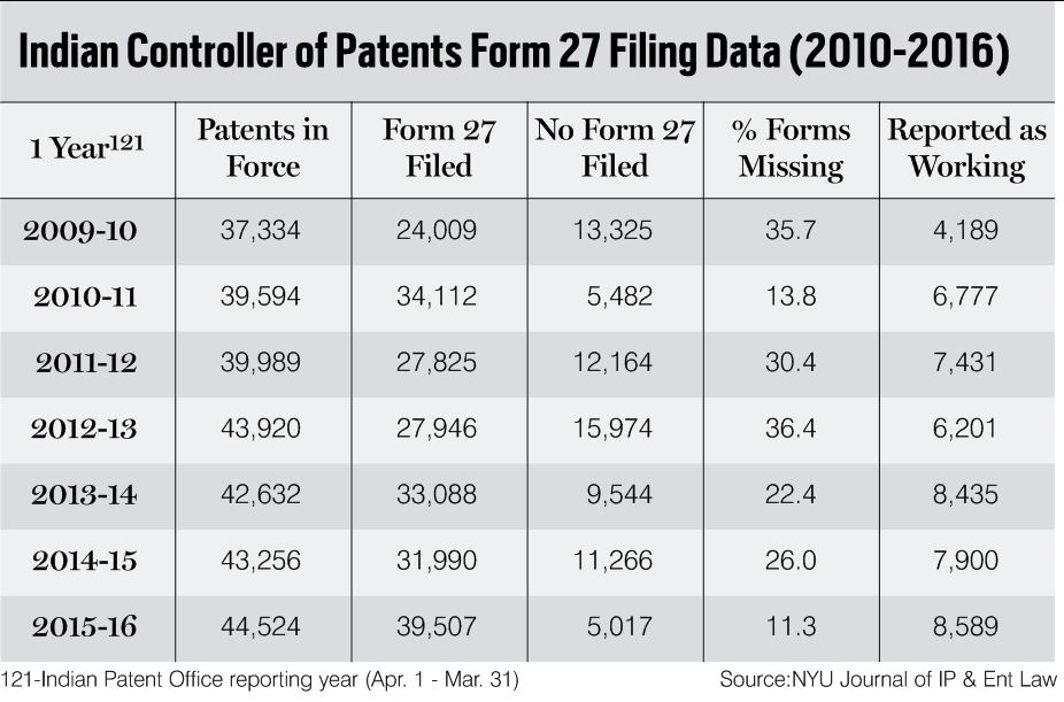

A perusal of the Annual Report (2012-13) of the Office of the CG shows that out of the 43,920 patents granted that year, 27,946 of them submitted Forms (Form-27) as required by Section 146 and Rule 131. But the fact that only 6,201 patents were found to be commercially working in India shows that neither the Patent Office nor the patentees even follow the general principles of law.

The Delhi High Court recently ordered that the CG’s office place a report before it upon completion of draft amendment to Rule 131 of the Patents Rules, 2003, the Form 27 prescribed therein. The office of CG submitted a timeline before the bench of Justice C Hari Shankar on its course of action—from inviting stakeholders’ suggestions to sending the draft of amended Form 27 to the law ministry, an exercise that is expected to take a year.

Form 27 is where statements are furnished by patentees and licensees, under sub section 2 of Section 146 of the Indian Patents Act, at the time of seeking a patent right. Section 146 (2) of the Indian Patents Act instructs the patent holders to furnish information related to the extent to which an invention has commercially worked in the country. It states that “every patentee and every licencee (whether exclusive or otherwise) shall furnish in such manner and form and at such intervals (not being less than six months) as may be prescribed statements as to the extent to which the patented invention has been worked on a commercial scale in India”.

Under Section 122 (b) of the Patents Act, failure to supply information will be punishable with fine up to Rs 10 lakh. “If no information is given in Form 27 and there is a request for compulsory licencing, how would the Cont-roller know whether the mentioned patent is being worked or not,” a senior official working with the Indian Patent Office told India Legal on condition of anonymity.

The concept of compulsory licence is that the government authorises a third party to make, use or sell a product that has been patented, without the need to get permission of the patent owner. Section 84 of the Patents Act states that any interested person may make an application to the Controller for grant of compulsory licence, any time after the expiration of three years from the date of the grant of a patent, on any of the following grounds:

(a) That the reasonable requirements of the public with respect to the patented invention have not been satisfied;

(b) That the patented invention is not available to the public at a reasonably affordable price;

(c) That the patented invention is not worked in the territory of India.

So is compulsory licencing a violation of the rights of the patent holder? Advocate Sreenath Namboodiri, Fellow, Centre for Economy, Development and Law, Kerala, disagrees. “Patent right is not an inherent right such as human rights; instead it is a state-granted right appreciating an inventor’s ingenuity. Such ingenuity is never exclusive, rather it develops through various factors. It is fed by the earlier inventions in that field,” said Namboodiri.

Basheer had also presented an RTI query checking whether action had been taken against those patentees or licencees who had not submitted Form 27.

It was revealed that no action had been taken against the defaulters. Many patentees, such as Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson, had stated in the Form, instead of furnishing information, that “as all the licences are confidential in nature, the details pertaining to the same shall be provided under specific directions from the Patent Office”.

On why no action has been taken against defaulters, a senior official with the Indian Patents office said: “If we receive a complaint regarding a person not filing information under Form 27, we will take action. But we haven’t received any complaints so far.”

A paper titled, “Patent Working Requirements And Complex Products”, published in the Journal of Intellectual Property and Entertainment Law by New York University studied the findings of Prof Basheer. An Annual Report is published by the Controller on statistics related to patent-filings. The data (see Table on Form 27 Filing) indicates that several number of patent holders do not file Form 27.

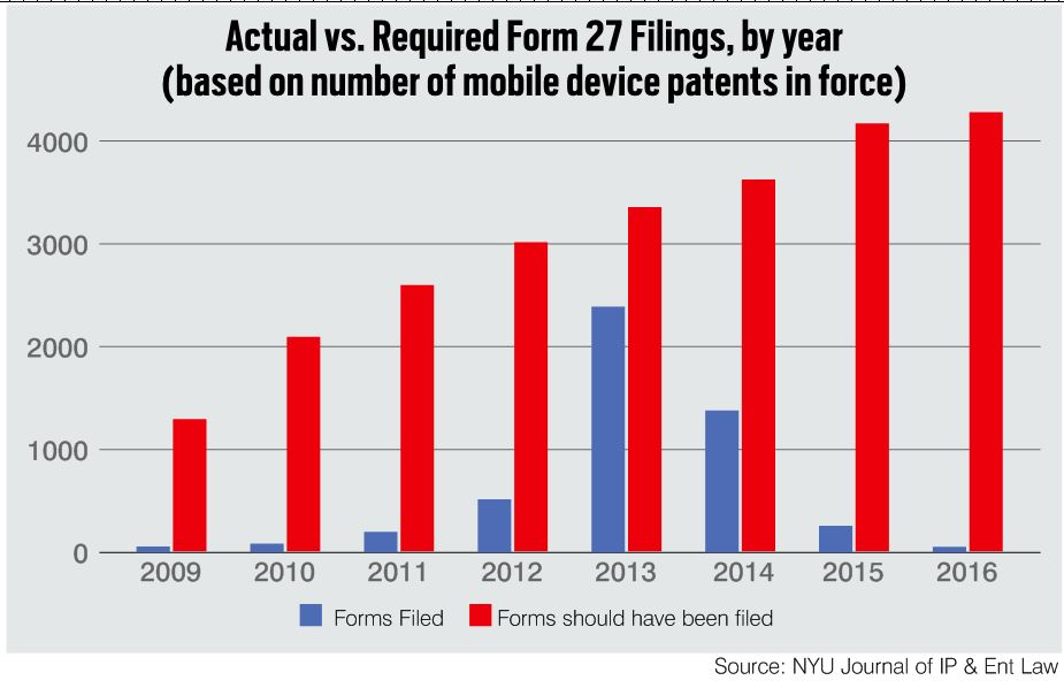

The number of Form 27 filed (see Table on Actual vs Required Form Filing Data) has fallen since it was first introduced in 2009. That year, only 36 Forms were filed, representing 2.8 percent of the 1,302 Forms. Since then, the ratio has been declining. In many of the patents for which Forms 27 were filed, the assignee made no indication of the working status of the patent.

Mobile companies have been particularly ingenious in evading queries. For example, one handset manufacturer, Nokia claimed that their patent portfolios are too vast to determine how particular patents are being worked in India. This was the company’s response in 82 separate Form 27 filings: “Nokia’s products and services are typically covered by tens or hundreds of the nearly 10,000 patents in our worldwide portfolio. We do not keep records of which individual patents are being employed in each of our products or services”.

Motorola says the nature of its invention makes it impossible for it to file the working status of its patent. Motorola declared so in several of its Forms: “It is not possible to determine accurately whether the patented invention has been worked in India or not, due to the nature of the invention.” Ericsson’s approach was slightly different. It stated that “while it is actively seeking opportunities to work the patent, there may have been some uses of the patented technology”, which means that there is no certainty over the patent being worked.

However, complying with the Delhi High Court’s order in Shamnad Basheer versus Union of India, the Indian Patent Office opened suggestions and comments from stakeholders on issues relating to working of patents and Form 27.

Suggestions poured in from a wide range of stakeholders, with 70 percent of them participating in the consultation process held by the Patent office. These stakeholders included law firms, advocates, academicians, patent officials, and so on.

Among the various suggestions that the Indian Patent office received, one was from the South Asian branch of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). It stated in its submission: “The US urges India to take the opportunity to significantly improve the ease of doing business, enhance predictability and certainty for innovative industries, align with international best practices, and help achieve National IP Policy, Start-up India and other national initiatives by eliminating the requirement for patentees to regularly file Form 27 statements.”

This, by many IP experts, is being seen as an interference and overt pressure by the USPTO in the internal policy decisions of India. Advocate Namboodiri told India Legal: “India cannot ignore the submission made by USPTO because it affects India’s bilateral relations with the US and our trade relations are too important. Therefore, it is important that India takes care of these countries interests when it comes to policy designing”.

The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) in April this year released the 2018 Special 301 Report, in which it has identified trading partners that do not protect and enforce Intellectual Property rights adequately, or else deny market access to US innovators.

The report calls on US trading partners to address IP-related challenges, keeping a special focus on countries that the US identifies on its Watch List and Priority Watch List. Unsurprisingly, like every year, this year too, the US has placed India in its Priority Watch List.

In fact, the US placing India in its Priority Watch List and USPTO’s submission to the Indian Patent Office should be considered together.

It is not just the USPTO, but there are several other domestic players too that are in favour of Form 27 being scrapped altogether. Or amended. Hindustan Unilever Limited, one of the leading Indian FMCG companies asked for either a legislative change to Section 146 (2) to make the details under Point 3 of Form 27 as “optional” or to amend Form 27 for better compliance.

However, Anubha Sinha of the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) supported the existence of Form 27. Sinha, in her submission, explains: “The information required to be provided in Form 27 is beneficial to all Indians as it prevents the patentees from creating blocking monopolies, i.e. obtaining and maintaining patents for the purpose of blocking others from developing technologies in the vicinity of the patented inventions.” This is also the underlying idea behind India’s patent policy.