Above: Karnataka High Court judge Justice Jayant Patel (inset); Lawyers protest against Patel’s transfer who was transferred to Allahabad

In a surprising move, the apex court has started to give bare details of reasons behind some of its decisions. However, naming those whom it cannot elevate as judges could backfire and lead to discontent

~By Venkatasubramanian

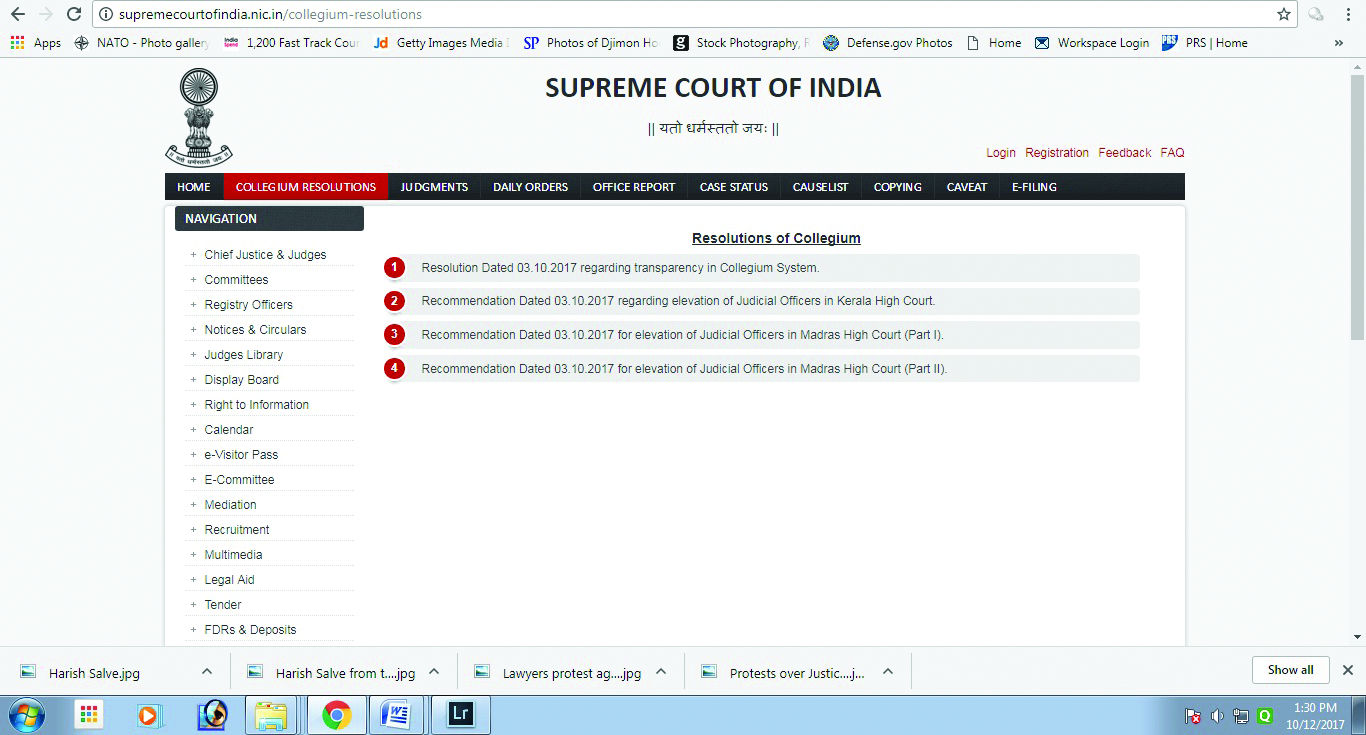

Several features of the Supreme Court’s recently launched website, supremecourt.gov.in, on the morning of October 6, were inactive for a few hours. Even as its users fretted, little did they know that they would be in for a surprise when the system started functioning again. And when it did, there was a surprise. A new tab, “Collegium Resolutions”, was seen added to the list of 10 options under Case Information. The tab led the user to a world of transparency, with the Collegium providing a text of its resolution passed on October 3, explaining, in brief, its rationale. Then followed the reasons, albeit the bare minimum, for its recommendations for elevating or not elevating judicial officers in the Kerala and Madras High Courts.

The Collegium’s historic move to become transparent was a welcome one and converted many of its hardcore critics. The Collegium was set up as a result of the Supreme Court’s judgment in the Second Judges case in 1993. It was meant to facilitate consultation with the government and to appoint and transfer judges. However, recent controversies made it look like an appendage of the government. But thanks to the recent move, its image will no longer be dented. And the significance of its timing is not lost on observers.

JUSTICE PATEL’S TRANSFER

The Supreme Court Collegium could not hide the fact that its sudden move towards transparency was a result of it coming under attack for its inexplicable decision to transfer a high court judge. The Collegium, comprising the five seniormost judges of the Court, could never have anticipated that a routine decision to recommend transfer of a judge from one high court to another would lead to a serious controversy, pitting it against lawyers and litigants. Its transfer in September of Karnataka High Court judge Justice Jayant Patel to Allahabad, which provoked his resignation, did precisely that.

Although the Collegium was used to criticism of its opaqueness, this time it did hurt, with lawyers in Karnataka and Gujarat where Justice Patel hails from, striking work for a day in protest against the transfer recommendation. Some of them were also preparing the ground to legally challenge the transfer and the Collegium’s way of functioning. This would have further embarrassed its members.

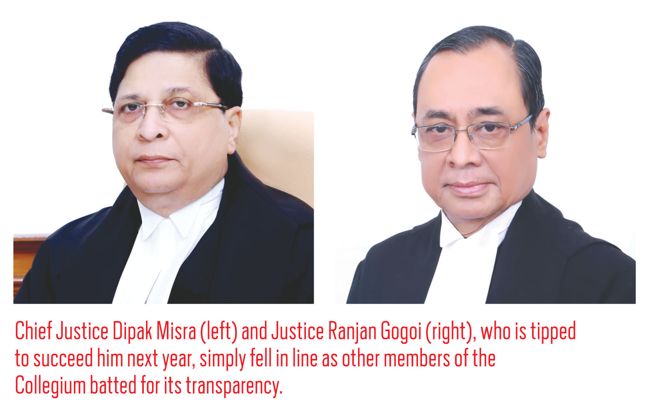

The embarrassment would have been acute as three members of the Collegium had earlier batted for its transparency as members of the Constitution Bench while setting aside the National Judicial Appointments Commission in 2015. They are Justices J Chelameswar, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph. The other two members, Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justice Ranjan Gogoi, who is tipped to succeed him next year, simply fell in line.

The Supreme Court’s Constitution Bench had emphasised in December 2015 the principle of transparency, apart from others, to reform the Collegium and its opaqueness. However, steps to implement its guidelines did not follow because of the tug-of-war between the government and the Collegium on the revised Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for appointments and transfers. The government insisted that the MoP must be revised to give it an undeclared primacy, while the Collegium was reluctant to agree to this. One of the clauses being insisted on by the government was to give it the prerogative to refuse a recommendation of the Collegium on the ground of national security.

EXTENT OF TRANSPARENCY

Although nothing prevented the Collegium from becoming transparent on its own earlier, it did not take that crucial step and seemed to be waiting for finalisation of the MoP. This led to questions being asked whether the Collegium would be inclined to take the other steps outlined in its December 2015 order without endlessly waiting for the revised MoP.

The other steps were the establishment of a secretariat to collect, process and provide inputs about the potential candidates for appointment as judges; formulation of eligibility criteria for appointments, including prescribing a minimum age for those in the zone of consideration for elevation to the Bench in high courts and the Supreme Court, and an appropriate mechanism and procedure for dealing with complaints against those being considered for appointments. These steps envisaged interactions with the appointees by the Collegium without sacrificing the confidentiality of the appointment process.

The decision to make the proceedings of the Collegium partly public has raised expectations that it will become fully transparent in stages. Among lawyers, the decision elicited mixed responses. A section of them felt that the move to disclose the reasons for not recommending a candidate found unsuitable by the High Court Collegium is fraught with consequences. Thus, on October 6, the website revealed why it could not recommend the appointment of four candidates found suitable by the High Court Collegium for appointment as judges of the Madras High Court. The disclosure of the identity of these candidates could affect the discharge of existing responsibilities, it was felt.

Senior advocate and former Solicitor General Harish Salve told a legal website that potential candidates may refuse to be considered for elevation because the disclosure of adverse remarks against them by the Collegium could harm their reputation and even create doubts about their suitability for their current jobs.

UNSUITABLE CANDIDATES

The Collegium thus found Vasudevan V Nadathur, judicial member, Income Tax Appellate Tribunal, unsuitable for elevation as a judge, although his name was recommended by the Collegium of the Calcutta High Court on November 28 last year. But the government of West Bengal had disagreed. The Collegium referred to its earlier decision to reject a similar recommendation to elevate Nadathur by the Bombay High Court Collegium on August 1, 2013. “Keeping in view the views of the consultee-Judges and the material on record, the Collegium is of the considered opinion that Shri Vasudevan V Nadathur is not suitable for elevation to the High Court bench,” the resolution uploaded on the website reads.

Such partial disclosure of facts regarding a candidate’s suitability for elevation, observers said, does more harm than good. The Collegium thus does not disclose the “material on record” which led it to conclude that Nadathur is not suitable for elevation. Nor does it reveal why “one of the two consultee-colleagues”—whom it did not identify—did not find Nadathur suitable for elevation. Going further, the reasons why the previous Collegium did not find him suitable for elevation in 2013 were also not disclosed.

Similarly, the Collegium has cited the material on record, including the report of the Intelligence Bureau, for not finding A Zakir Hussain, Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate, Egmore, Chennai, and Dr K Arul, District Judge and Additional Director, Tamil Nadu State Judicial Academy and Officer on Special Duty, Madras High Court, suitable for elevation as judges of the Madras High Court. The public is at a loss in understanding what the material on record and the report of the IB revealed, and whether it would compromise the discharge of their existing duties.

The Collegium has also found after considering the material on record, including the views of the consultee-judges and the “Judgment assessment report”, S Ramathilagam, R Tharani, and P Rajamanickam suitable for elevation as judges of the Madras High Court. Full transparency would demand that the Collegium also put on the website the specific views of the consultee-judges and a copy of the judgment assessment report which it relied on.

Again, while explaining the merits of T Krishnavalli, who was recommended for elevation as a judge of the Madras High Court, the Collegium referred to her judgments being rated by the Judgment Committee as “Good/ Average” without informing the readers how these criteria are arrived at.

The Collegium has observed that professional competence of a candidate cannot be adjudged on the basis of unconfirmed/unsubstantiated inputs. While the Collegium is obviously satisfied with the inputs it received about the candidates whom it recommended for appointment, the public remains clueless about its reasons for satisfaction. So the Collegium has to make an extra effort to disclose them as well.

Curiously, the Supreme Court Collegium appears to have received a number of representations from senior judicial officers whose claims to be elevated as judges were rejected by the High Court Collegium (comprising the High Court Chief Justice and two seniormost judges of the High Court). In each of these representations, the Supreme Court Collegium has expressed its agreement with the reasons cited by the High Court Collegium. The disclosure of reasons could help the public know whether the High Court Collegium rightly rejected their claims or not. Hopefully, this will be a work in progress.