In a major policy shift, the Election Commission has decided to serve notice to the political party and not the star campaigner for Model Code of Conduct violations. Has this been done to insulate powerful wrongdoers?

By Sanjay Raman Sinha

In a notable departure, the Election Commission (EC) has changed its policy for violations of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) by star campaigners. Now instead of sending a notice to individuals, their respective political parties will be notified.

The rule change came to light when the EC sent notices to the BJP and the Congress after complaints were received against Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Rahul Gandhi. Both the parties accused each other of inciting hatred and division based on religion, caste, community and language. The notices specified that individual star campaigners are responsible for their own speeches and the EC may, on a “case-by-case basis” hold political parties accountable for any MCC violations by their campaigners.

Normally, the EC dealt with MCC violations by sending notices to individual campaigners rather than their political parties. This approach, while effective in holding individuals accountable, often left parties unscathed, allowing them to distance themselves from the actions of their star campaigners.

However, recent developments mark a departure from this practice. Now, political parties will have to shoulder the responsibility of their star campaigners, be it the prime minister or a party president. This means that the “VIP” in question will be spared from receiving notice and being personally liable for his misdeeds and the spotlight and onus will shift to the party.

It is apparent that by holding political parties responsible for MCC violations of their star campaigners the EC is enhancing accountability within the electoral process. Parties can no longer absolve themselves of responsibility by blaming individual campaigners. The prospect of facing repercussions at the party level may deter individuals from indulging in reckless actions contrary to MCC guidelines. This could lead to greater adherence to electoral norms and a more level-playing field for all contestants.

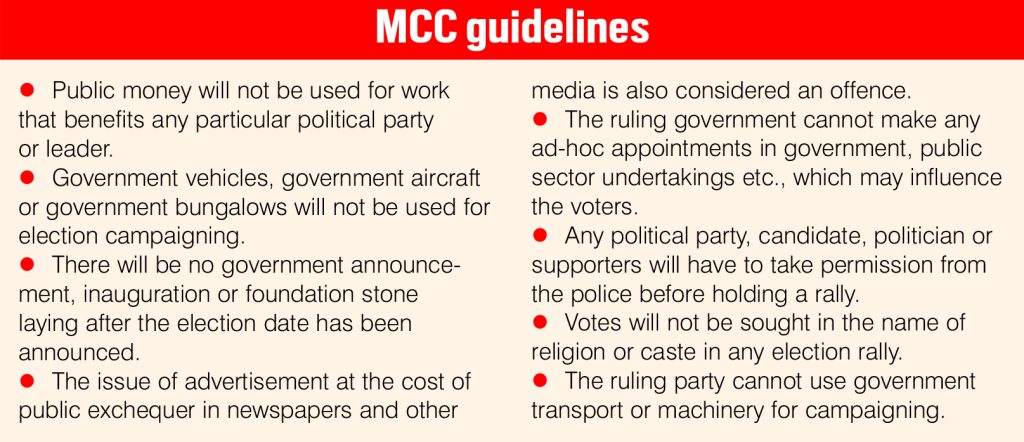

The MCC is a set of guidelines issued by the EC to regulate the conduct of political parties and candidates during elections. It aims to ensure free and fair elections by preventing malpractices and maintaining a level-playing field. However, violations of the MCC are not uncommon, with political leaders often accused of flouting its norms for electoral gains.

Former Chief Election Commissioner TS Krishnamurthy told India Legal: “Though the Model Code of Conduct has no constitutional or statutory sanction, the Supreme Court in various judgments has upheld the MCC; the judiciary has generally recognised the MCC as a tool of election management. I have been suggesting certain changes. In areas of major violations, the EC should be given statutory powers to impose monetary penalty and disqualify for a short period of three to five years violators of MCC or those who instigate violation of the MCC.”

Fingers have often been pointed at the EC for its alleged partisan role in resolving election disputes. The EC’s decision to target specific parties for MCC violations has been often perceived as biased or politically motivated. In a highly polarised political environment, such actions could further exacerbate tensions and erode public trust in the electoral process.

The EC’s decision to hold parties accountable sets a precedent that could have implications for future electoral disputes. It establishes a framework for adjudicating MCC violations at the party level. It also devolves responsibility and accountability to the party to resolve the violation issue. The EC as a watchdog can monitor how efficacious the move is.

There have been various cases of MCC violations cutting across party lines.

- Recently, the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee moved a plea before the Madras High Court urging it to direct the EC to ask Modi for an explanation for allegedly making hate speeches. “Mr Modi is solely responsible for these inflammatory remarks, derogative and divisive speeches. This leniency of the ECI sends a wrong signal to the citizens and undermines the integrity of our nation’s whole electoral process,” the plea stated.

- The EC also censured YSRCP supremo and Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister YS Jagan Mohan Reddy and Opposition leader N Chandrababu Naidu for violating the MCC for personal attacks against each other.

- In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, several BJP leaders faced allegations of MCC violations, including Prime Minister Modi. During a rally in Wardha, Maharashtra, he allegedly violated MCC’s guidelines against invoking the armed forces in campaigns.

- During the same election, the Congress faced criticism for distributing pamphlets containing defamatory content against BJP leaders. The EC took cognizance of the matter and issued notices to the party.

- During the 2021 West Bengal assembly elections, the Trinamool Congress faced accusations of MCC violations, including violence and intimidation of Opposition candidates. Instances of booth capturing and voter intimidation were reported from several constituencies.

- In the 2022 Uttar Pradesh assembly elections, the Samajwadi Party (SP) was accused of violating the MCC by making inflammatory speeches aimed at stoking communal tensions. The EC issued warnings to several SP leaders and monitored their campaign activities closely.

Upon receiving complaints of MCC violations, the EC initiates inquiries and issues warnings. These notices serve as warnings and require the recipients to explain their actions within a stipulated timeframe. In cases of serious violations, the EC may censure the erring parties or candidates and take punitive action. It employs various measures such as surveillance cameras, flying squads and video surveillance teams to monitor campaign activities and ensure adherence to the MCC.

The MCC kicks into action as soon as the election date is announced and continues till the counting of votes. With the implementation of the MCC, many rules come into force.

The Representation of the People Act (RPA), 1951, provides a rudimentary legal backing to the MCC and empowers the EC to regulate electoral conduct. Section 123 of the RPA prohibits the appeal by a candidate or his agent or by any other person to vote or refrain from voting on the grounds of religion, race, caste, community, or language. Section 125 deals with penalty for promoting enmity between classes in connection with an election. Section 126 prohibits the conduct of exit polls during the election period to prevent influencing voters.

Several court verdicts have reinforced the importance of upholding the MCC and penalising violations. In the landmark Mohinder Singh Gill vs The Chief Election Commissioner (1978) case, the Supreme Court upheld the EC’s authority to hold free and fair elections and enforce the MCC. In S Subramaniam Balaji vs Government of Tamil Nadu (2013), the Madras High Court upheld the disqualification of a candidate for distributing cash to voters, emphasising the need to curb electoral malpractices.

The MCC began with the Kerala assembly elections of 1960. The Code was prepared only after talks and consent of political parties. After the 1962 general elections, the code of conduct was made applicable in the 1967 Lok Sabha and assembly elections also. Later, more rules were added to the Code. While the MCC is not part of any law, some provisions are implemented on the basis of IPC sections. Despite all these measures, political parties and candidates do not take them seriously and in every election, MCC violations comes to light.

Krishnamurthy added: “I have also suggested a separate law governing the functioning of political parties. It will cover some aspects like funding, etc. The Justice Venkatachaliah Commission which was set up to review the functioning of the Constitution has said on the basis of our recommendation that a separate comprehensive law is needed to regulate the functioning of political parties.”

In September 1979, the EC called a meeting of political parties and amended the code of conduct. It was implemented in the general elections held in October 1979. However, a lot has changed since the adoption of the MCC in 1960. Though the MCC has emerged an instrument for free and fair elections, the onus lies with the EC on how to use it.

TN Seshan, the tenth chief election commissioner, gave the EC strength regarding its inherent statutory powers and maintained its freedom and sanctity. It is time others holding this August post take a leaf out from his book and treaded his path.