The central government recently told the Supreme Court that freebies promised by political parties before polls is an “economic disaster”. Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, representing the central government, said that the populist announcements distort the informed decision making of the voter and a voter should know what’s going to fall on him. He told the bench: “This is the way we are heading towards economic disaster”.

The apex court suggested that an expert body, comprising representatives of the NITI Aayog, Finance Commission, RBI, political parties and other stakeholders, should examine the pros and cons of freebies, while acknowledging that it is a serious issue.

Mehta suggested that the Election Commission of India (ECI) should apply its mind on the matter and have a relook. However, the ECI’s counsel said that its hands were tied by a judgment of the apex court on freebies.

A bench headed by the Chief Justice of India (CJI), NV Ramana, said this is a serious issue and the ECI and the central government cannot say that they cannot do anything in the matter. He said the government and the ECI have to consider the issue and give suggestions. The CJI sought suggestions from senior advocate Kapil Sibal, who was present in the courtroom for another matter. Sibal suggested that the ECI should be kept out of the matter as it is a political and economic issue and there should be a debate in Parliament on it.

The bench, also comprising justices Krishna Murari and Hima Kohli, said no political party would like to take out freebies and all want freebies. It further noted that these are all policy matters and everyone should participate in the debate. “We’ll say Finance Commission, political parties, opposition parties, all of them can be members of this group. Let them have a debate and let them interact. Let them give their suggestions and submit their report,” the bench noted.

The top court asked the centre, ECI, petitioner and Sibal to give suggestions within a week on the composition of an expert body that will examine how to regulate freebies and give its report to centre, ECI and the Court. It was hearing a PIL filed by advocate Ashwini Upadhyay against the announcements made by political parties for inducing voters, through freebies, during elections. Upadhyay argued that the ECI should debar state and national parties from making such promises. He claimed that the promise or distribution of irrational freebies from public funds before polls shakes the roots of a free and fair election and vitiates the purity of the election process.

The plea sought a direction from the top court to declare that the promise of irrational freebies, which are not for public purposes, from public funds before election violates Articles 14, 162, 266(3), and 282 of the Constitution. It further contended that a condition should be imposed on the political party that it would not promise or distribute irrational freebies from the public fund.

The bench had on January 25 issued notices to the centre and the poll panel on the matter. Last month, the Court asked the central government to engage with the Finance Commission on the issue of political parties inducing voters through freebies and examine if there is a possibility to regulate them by taking into account the money spent on freebies.

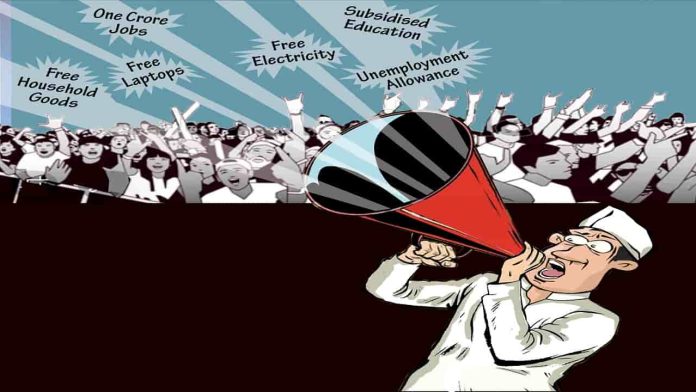

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, recently, cautioned people against what he called a “revadi” culture of offering freebies for votes and said this is “very dangerous” for the development of the country. Promising pre-poll sops to voters has been a common custom among India’s politicians for decades. From cash to liquor, household gadgets, scholarships, subsidies and foodgrains, the options are endless.

The late Tamil Nadu chief minister and AIADMK leader J Jayalalithaa was in many ways one of the pioneers of the freebie culture. She promised free power, mobile phones, Wi-Fi connections, subsidised scooters, interest-free loans, fans, mixer-grinders, scholarships, and more, to the voters. The Amma Canteen chain started by her was also a huge success. She must have picked up some tips from one of her predecessors, chief minister CN Annadurai, who in the 1960s announced a kilogram of rice for one Rupee.

In 2013, the Akhilesh Yadav government in Uttar Pradesh announced an ambitious free laptop scheme for students that many believed won him great political capital, particularly amongst the youth.

The Arvind Kejriwal-led Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) at present appears to be one of the biggest proponents of the freebie model of politics. Before the 2015 assembly elections in Delhi, in which it registered a famous victory, the AAP promised a reduction of consumers’ electricity expenditure by 50% through an audit of power distribution companies and 700 litres of free water per day to every household.

Kejriwal recently promised to create 10 lakh government jobs in Gujarat and a Rs 3,000-monthly unemployment allowance for young people if his government gets voted to power in the state. If AAP forms a government in Gujarat, the party will ensure that each unemployed youth gets a job in the next five years, Kejriwal said, while addressing a public rally at Veraval town of Gir Somnath district in the Saurashtra region. Assembly elections are due by the end of this year in Gujarat, where Kejriwal’s party is trying to gain a foothold. His announcement of unemployment allowance is a new addition to the offer of free water and electricity that got huge support in Punjab.

Since the Finance Commission is a constitutional body and plays a vital role in evaluating the state of finances of the Union and state governments and gives recommendations on distribution of tax revenues between the Union and the states and amongst the states themselves, it can impose restrictions on such revenue luxuries. Not just this, the ECI can also penalise such political parties and even prohibit contesting elections by such candidates based primarily on these promises or can increasingly regulate this addiction like on the limit of spending on election campaigns.

The strongest tool and antidote to this opium is in the hands of the lawmakers themselves who can make laws in Parliament against this practice.

—By Abhilash Kumar Singh and India Legal Bureau