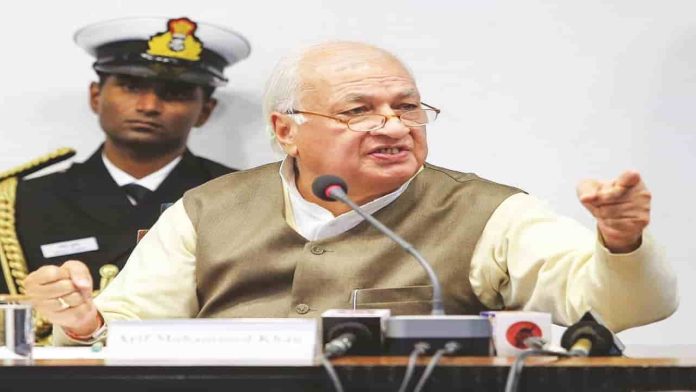

The friction between the CPI(M)-led government in Kerala and Governor Arif Mohammad Khan—who is the chancellor of all the universities—over appointment of vice-chancellors (VCs) in various universities has become a major political issue. The governor recently said that he was under political pressure to re-appoint Professor Gopinath Ravindran as the VC of Kannur University even after Raj Bhavan had notified a search committee to look for a new VC.

Earlier, the governor was offended when the cabinet gave approval to a draft bill to curtail the powers of the governor by increasing the number of members of the search committee for appointment of university VCs. Last week, the bill got cabinet approval and is likely to be introduced in the next session of the legislative assembly. This followed a government-appointed commission headed by NK Jayakumar, former VC of the National University of Advanced Legal Studies, which made recommendations to ensure that the governor, as chancellor, does not play an overarching role in state universities.

As per the clauses in the proposed bill, the number of members in the search committee might be elevated from the present three to five. At present, the search committee is a three-member body comprising representatives of the chancellor (the governor), University Grants Commission (UGC) and the concerned university. It submits a panel of names jointly or separately to the chancellor, who then makes the final selection.

As per the proposed bill, the search committee now will also have a representative of the government and the vice-chairperson of the Kerala State Higher Education Council. In case of a dispute, the decision of the majority shall prevail. With three of the five members in the panel likely to adopt a pro-government stance, the UGC nominee and the nominee of the chancellor would be reduced to mere spectators. In effect, this would curtail the governor’s powers to appoint the VC and the government would gain the upper hand.

Ramesh Chennithala, former opposition leader and Congress legislator, said the state government has a hidden agenda behind the proposed bill and the CPI(M) wants to bring all state universities under the party’s control. This will kill the autonomy of the universities in the state. He added that the syndicates and senates of the universities are controlled by the CPI(M), which is keen to nominate relatives of party leaders in universities. The bill should be withdrawn, he said.

The Tamil Nadu legislative assembly adopted two bills empowering the government to appoint VCs to state universities on April 25 and sent them to the governor for approval. Tamil Nadu Universities Laws (Amendment) Act, 2022, and Chennai University (Amendment) Act, 2022, were passed by replacing the term “chancellor” with “government”, referring to the power of appointing VCs. The Tamil Nadu government tabled one more bill on May 5, empowering itself to appoint the vice-chancellor of the Ambedkar Law University.

According to Article 361 of the Constitution, the governor shall not be answerable to any court for the exercise and performance of the powers and duties of his office. The governor approving a state government’s policies is more an unwritten practice upholding the essence of federalism. If the governor refuses to do it, it causes a crisis in the administration of the state government which is detrimental to the spirit of democracy.

In most cases, the governor of a state is the ex-officio chancellor of the universities in that state. While the governor’s powers and functions as the chancellor are laid out in statutes that govern the universities in a state, his/her role in appointing VCs has often triggered disputes with the state government.

In Kerala’s case, the governor’s official portal asserts that “while as Governor he functions with the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers, as Chancellor he acts independently of the Council of Ministers and takes his own decisions on all University matters”. In marked contrast, the website of Rajasthan’s Raj Bhawan states that the “Governor appoints the Vice Chancellor on the advice/in consultation with the State Government”.

The political tug of war over educational appointments started in November 2021, when Kerala higher education minister R Bindu requested the governor to re-appoint Kannur University VC, 61-year-old Gopinath Ravindran, for another term of four years. Ravindran is above 60 and the Kannur University Act says that no person above the age of 60 shall be appointed as VC.

In his letter, the governor wrote that he had tried to convince the legal advisor to the chief minister that re-appointment does not amount to an extension of the term of an incumbent VC. Then, the Kerala government amended the University Act by taking away the powers of the chancellor to appoint the University Appellate Tribunal without consulting the High Court on the matter. When Bindu met the governor, she told him it was a precedent in Kerala that the governor must appoint his nominee in the VCs search committee as per suggestions of the government. Khan refused to budge.

The Kerala fracas mirrors similar incidents in other states. In West Bengal, in 2019, to curb the power of then state governor Jagdeep Dhankhar as the chancellor of all state-run universities by default, the state government tabled new rules in the state assembly, where it was mentioned that the governor’s nod will no longer be required to call a senate meeting and the chancellor’s approval will not be required for selecting candidates for honorary degrees at the convocation. The new rules named, West Bengal State Universities (Terms and Conditions of Service Vice Chancellors & the Manner of Procedure of Official Communication) Rules, 2019, were introduced to the West Bengal Universities and Colleges (Administration and Regulation) Act, 2017. Sources in the education department said that the state had been mulling steps to curb the chancellor’s power after Dhankhar had said that only the chancellor, vice-chancellor and the administrative bodies of a university had the right to run the daily affairs of the institute, no one else.

Similarly, the Maharashtra legislature on December 28, 2020, passed the Maharashtra Public Universities Act Amendment Bill that curtails the powers of the governor in appointing VCs of various universities by changing the procedure. Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari approached the Union home ministry seeking views of then President Ram Nath Kovind over amendment in the Maharashtra Public Universities Act that reduces his powers. Koshyari was of the view that the provisions of the bill were not in conformity with the regulations under UGC Act, 1956.

Kerala is the latest state to make legislative efforts to curb gubernatorial powers in appointments.

—By Adarsh Kumar and India Legal Bureau