In a laudable move by the centre, property cards have been distributed to those living in rural segments in order to deliver land ownership rights and allow them to use this as an asset for borrowing funds.

By Shivanand Pandit

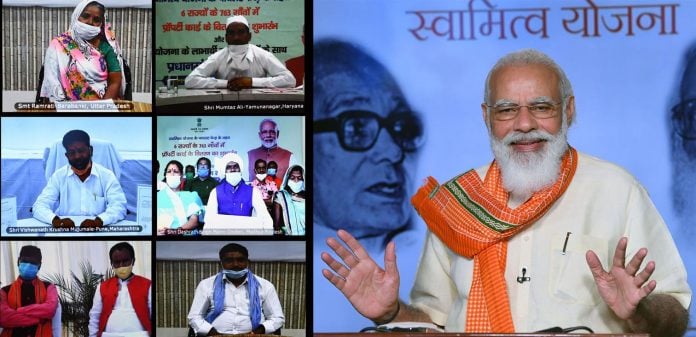

ON April 24, 2020, Panchayati Raj Diwas, the prime minister unveiled the SVAMITVA (Survey of Villages and Mapping with Improvised Technology in Village Areas) Yojana. On October 11, 2020, the physical distribution of property cards online was started under this scheme.

It aims to record residential land possession in the rural segment by employing the latest technology such as drones and cutting edge survey methods with the cooperative efforts of the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, State Panchayati Raj Department, State Revenue Department and Survey of India. It also aims to allow village dwellers to utilise the property as an asset for borrowing funds and additional monetary gains.

By assuring the physical delivery of property cards by state governments, the Prime Minister’s Office proclaimed the scheme a “historic move”. It said it would permit approximately one lakh land owners to download their property cards via SMS link on their mobile phones. Beneficiaries of the scheme will be from 763 villages in six states, including 346 from Uttar Pradesh, 221 from Haryana, 100 from Maharashtra, 44 from Madhya Pradesh, 50 from Uttarakhand and two from Karnataka. The scheme is silent on the other states.

A separate card for every property in the village will be prepared by state governments using precise measurements supplied by drone charting. These cards will be acknowledged by the department of land revenue records. The property database will also be kept at the panchayat level, permitting collection of related taxes from the owners.

Thirty years ago, Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto Polar had projected that uncertain property rights had under-capitalised 80 percent of the world. According to him, trillions of dollars were lying as dead capital globally.

In 1980, inspired by the Torrens system present in Australia, the DC Wadhwa Committee had urged titling, whereby the state provides compensation if a land title granted by it is successfully challenged. In spite of the property record upgrading scheme introduced in 1988 and repurposed as the National Land Records Modernisation Programme in 2008, comprehensive digitisation did not take place. But according to the Digital India Land Records Modernisation Programme, approximately 90 percent of rural communities in India have been digitised.

Read Also: How to Write a Legal Contract

This may not be entirely true as an examination reveals that only 61 percent of these communities have digitised mutation records. Furthermore, only 41 percent have a clear record of rights and survey or resurvey work has been finalised in only 11 percent villages.

While states that have initiated land modernisation have done better on the digitisation of database, they trail in terms of fineness of land records. This has been clearly revealed by the 2019-20 NCAER Land Records and Services Index. Attempts by the government in 2011 and 2013 in accordance with the Financial Services Committee also did not yield the right output.

The fiscal strength of gram panchayats in India largely hinges on accurate land records, which will help to engender revenue. None the less, they have a scanty track record of producing incomes through property tax. According to the Economic Survey of 2018, only 19 percent of the probable property tax was collected by gram panchayats.

A major cause for the truncated collection would be the absence of property data such as where are they located, are they residential or commercial, what should be the pertinent tax rate and who should be taxed.

During times of crisis, everyone realises the importance of precise property records. Recently, huge areas of seaside Odisha and West Bengal were destroyed by cyclone Amphan. Any relief attempts to help people reconstruct their houses would benefit enormously from land records that detect who lived where, the borders and the size of their land. In the absence of these, there is the possibility of the weakest sections losing out on the little they had, with no ability to claim compensation from the government.

Thus, the SVAMITVA scheme has been initiated due to poor or inaccurate land records in India and it is hoped it will fix this gulf by creating geospatial records of all rural properties. Considering the success of pilot cadastral survey plans in Haryana and Maharashtra, where property cards were issued, the scheme aspires for a pan-India examination so that it provides long-term benefits to villagers.

The need for this Yojana was realised as many villagers did not own papers demonstrating possession of their land. In most states, surveys and dimensions of colonised areas in villages had not been done. So this scheme is meant to plug the above gap and deliver ownership rights to these people. It should go a long way in resolving property disputes in rural areas and is likely to become an equipment for empowerment and entitlement, thereby reducing social conflict.

Land and borders are well-known for daunting any policy reform in India. Although the government has declared the scheme as a game changer and gears up to execute the plan, four crucial aspects have to be considered in order to safeguard and guarantee the success of the strategy.

Firstly, to generate grander recognition of the procedure and eradicate possible disagreements, the community has to be engaged from the beginning to sketch land frontiers. This will bring transparency.

This was observed in two instances. While drone charting plots in Maharashtra, the survey department followed the bottom-up method and requested people to mark their own boundaries. While executing the Jaga mission in Odisha, shanty town inhabitants were involved in the border separation. Consequently, this gave the desired outcome, decreased clashes and efforts to make digital charts of the slums were largely accepted and respected.

Secondly, strong awareness about interpretation and access of digital property records has to be created among people. This will circumvent information lopsidedness and assure smooth access of records.

Land has unfathomable origins in social power configurations, including caste and gender favouritisms. A large section of vulnerable people such as Dalits, women, tenant agriculturists and ethnic communities are often disqualified from accessing land, despite having genuine entitlement. It is very important to protect the lawful right of weaker sections.

Thirdly, even though the government generally brands its reforms as simple and historical, a majority of them have created numerous grievances for citizens. The SVAMITVA scheme may not be an exception and Odisha’s KALIA and Mo Sarkar programmes have already taught us lessons.

Therefore, the government has to introduce an effective remedial arrangement to handle public apprehensions in a crystal clear style. By learning lessons from Mexico, the government can establish fast-track land dispute courts, put into operation the Torrens model or have title insurance under the RERA Act. This can reduce land disputes, which comprise almost 66 percent of all civil cases in courts.

Fourthly, to guarantee uninterrupted credit flow to village zones, land records have to be updated because credit demands merchantable security. Therefore, it is important to ensure there is a purposeful and practical marketplace for the primary security, namely land. The government should also streamline judicial and governing formulas to boost consumer conviction and embolden transactions in these areas.

The SVAMITVA scheme is indispensable for a nation like India whose soul and spirit live in its villages where nearly 70 percent of the population dwells and where around 61 percent of India’s land mass is. The scheme will liberate rural people and bring fiscal constancy to deprived people if properly designed and implemented.

Therefore, the central government should roll out a power packed land titling by law, although some states such as Rajasthan and Maharashtra have already put into practice their own laws in 2016 and 2019, respectively. On the contrary, if the central government fails to bring all inclusive regulation, the ground reality will be tedious.

—The writer is a financial and tax specialist, author and public speaker based in Margao, Goa