Above: A Punjab National Bank branch in Delhi/Photo: Anil Shakya

Despite government assurance that NPAs can be recovered, at least 70 percent remain beyond reach, even with legal options available to the banks

~By Sujit Bhar

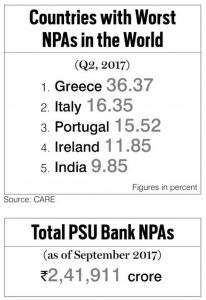

Of the over Rs 2.41 lakh crore non-performing assets (NPA) that public sector banks had piled up till September 2017, at least Rs 1.68 lakh crore, or 70 percent, cannot be recovered, going by the average recovery rate in such cases. While banks can legally take action for recovery, the asset value that they can now pursue would have shrunk drastically. These are called impaired assets. This leaves recovery of personal possessions such as Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher Villa in Goa the only other option.

The overall NPA amount of Rs 2.41 lakh crore was a figure admitted by Shiv Pratap Shukla, minister of state for finance, in the Rajya Sabha on April 3. This did not include the amounts looted by diamond traders Nirav Modi and Mehul Choksi from Punjab National Bank (PNB) and was arrived at before the unravelling of ICICI Bank’s sweetheart deal to Videocon and before Axis Bank’s Shikha Sharma’s position at the helm was found untenable.

However, the minister insisted that these loans “continue to be liable for repayment. Recovery of dues takes place on an ongoing basis under legal mechanisms, which include, inter alia, the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, Debts Recovery Tribunals and Lok Adalats. Therefore, write-offs do not benefit borrowers”.

However, the minister insisted that these loans “continue to be liable for repayment. Recovery of dues takes place on an ongoing basis under legal mechanisms, which include, inter alia, the Securitisation and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, Debts Recovery Tribunals and Lok Adalats. Therefore, write-offs do not benefit borrowers”.

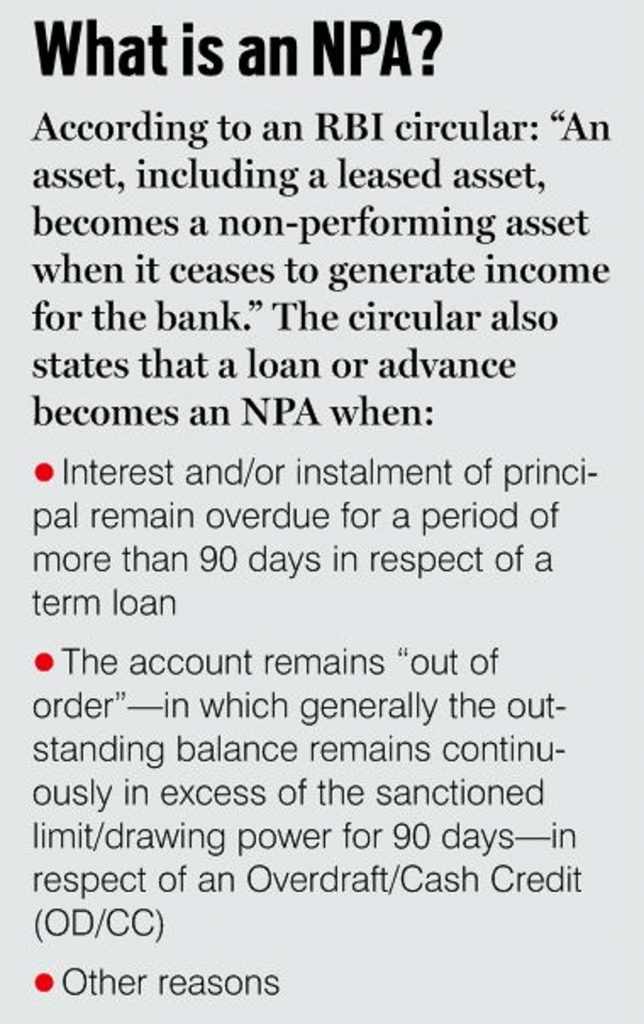

In short, it means that banks retain the legal option to enforce payment. Herein lies the catch. According to reputed corporate lawyer Virender Ganda, the average recovery rate is 25-30 percent in cases of NPAs (see box). Technically, renaming a loan as an NPA is an accounting procedure to remove a large sum forwarded as a bad business decision. By the same logic, the bank’s assets reduce by that many crores, which also means that its overall performance plummets as it is not allowed to accept deposits beyond stated asset levels and cash reserve ratio amounts kept with the RBI against deposits.

Ganda said: “While the enforcement process can continue, restrictions imposed by the RBI would not allow the bank to take in fresh deposits, hence harming its future prospect of other loan advancements. Loans and their interests are a bank’s principal activity.”

Regarding loan recovery, the RBI’s instruction to banks is simple. It says: “In the absence of a clear agreement between the bank and the borrower for the purpose of appropriation of recoveries in NPAs (i.e. towards principal or interest due), banks should adopt an accounting principle and exercise the right of appropriation of recoveries in a uniform and consistent manner.”

The RBI also states: “Banks are required to classify non-performing assets further into three categories based on the period for which they have remained non-performing and the realisability of the dues: Sub-standard Assets, Doubtful Assets, Loss Assets.”

Of these, the last category (Loss Assets) is critical. The definition of this category states: “A loss asset is one where loss has been identified by the bank or internal or external auditors or the RBI inspection but the amount has not been written off wholly. In other words, such an asset is considered uncollectible and of such little value that its continuance as a bankable asset is not warranted although there may be some salvage or recovery value.”

Banks have declared NPAs but have not revealed how much is due in which category. In his reply, the minister also stated that the “RBI has apprised that borrower-wise credit information is not available for disclosure under Section 45E of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. Section 45E provides that credit information submitted by a bank shall be treated as confidential and not to be published and otherwise disclosed.” For publicly traded companies, however, such information is readily available with a little search.

Banks have declared NPAs but have not revealed how much is due in which category. In his reply, the minister also stated that the “RBI has apprised that borrower-wise credit information is not available for disclosure under Section 45E of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. Section 45E provides that credit information submitted by a bank shall be treated as confidential and not to be published and otherwise disclosed.” For publicly traded companies, however, such information is readily available with a little search.

The basic idea of recovery would be to make sure that the asset value being targeted for recovery remains steady. In the case of an NPA, the first thing to be hit is the goodwill of the company. This erodes a large portion of the assets value. “Bank CEOs, chairpersons and other head honchos have been treating all these deposits in their banks as free money, to be given to whoever suits their whims and fancies,” Ganda told India Legal. “In the process, little due diligence was done to ensure that the loans advanced were matched by sufficient collateral.”

Referring to the Nirav Modi and Choksi cases, he said that the asset base of Gitanjali Gems, for example, was so low that it deserved little or no loan. The LoUs were not backed by collateral and the money advanced was too overwhelming, considering the merchants’ India-based assets. “Assessing the value of a diamond in India (where gold is the standard) is a difficult task,” he said. “Plus, if the underlying quality of the asset (diamond) was doubtful, then the entire exercise was dubious.” Hence, talk of recovery—even though legally tenable—is shooting in the dark.

According to CARE Ratings, in the second quarter of 2017, India’s NPAs stood at the fifth spot in the world.

This was behind Greece, Italy, Portugal and Ireland. India’s NPA ratio is 9.85 percent, which has been categorised as “very high”. The burden now falls on the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code and the National Company Law Tribunal to try and lower these figures through restructuring and recovery. But the task is easier said than done.