Above: The drug menace in Punjab has claimed the lives of at least 27 young people in June, say media reports

While the drug problem in Punjab calls for a concerted all-out war, recent steps initiated by the Amarinder Singh-led Congress government expose its knee-jerk response

~By Vipin Pubby in Chandigarh

Rattled by an online campaign and protests planned against the drug menace in Punjab in the wake of increasing deaths due to overdose and use of spurious drugs, the Capt Amarinder Singh government went into overdrive and announced a series of counter-measures.

While the state government had been claiming that there were just two deaths due to substance abuse or use of spurious drugs during June, the media and social organisations claimed that at least 27 young people had lost their lives. During the campaign for the Assembly elections last year, Capt Singh had taken a public oath on the Gutka (a Sikh religious book) to tackle the problem within four weeks of coming to power. He was soon to realise that it is hard to match words with deeds once you assume power. Having found it impossible to eradicate the widespread menace in such a short time, he set up a special cell to deal exclusively with the problem by unleashing a campaign against drug peddlers.

The sudden and sharp increase in the number of deaths of addicts led to a public outcry with opposition parties like the Aam Aadmi Party and the Shiromani Akali Dal taking the government to task over the issue. This in turn led to a knee-jerk response from the government which announced a series of steps, almost all of which have evoked controversy.

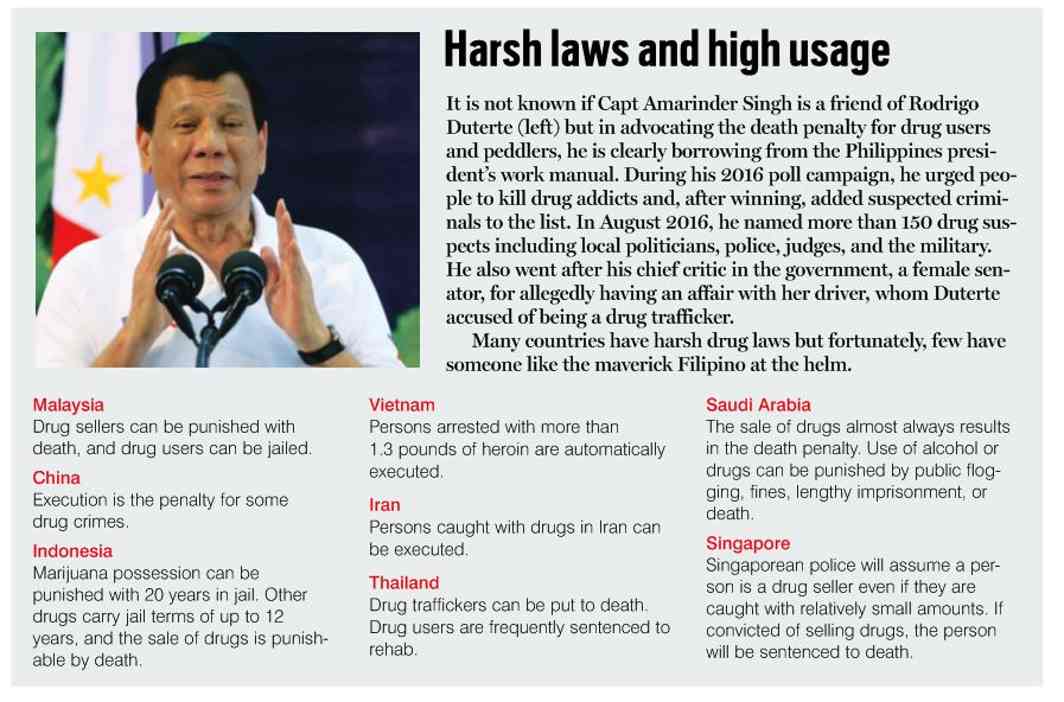

The first one, which sent shock waves all around, was the decision to seek the death penalty for even first-time offenders. The Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, provided for the death penalty to repeat offenders but Capt Singh wrote a letter to Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh arguing that it meant that “a person can indulge in these nefarious activities and get away at least once, causing substantial damage to the youth and the society”. He said “this should not be allowed to happen and even first-time offenders should be awarded death penalty for offences which are clearly elaborated in Section 31 A of the NDPS Act, 1985”. The chief minister further argued that “it would help us in effectively containing if not eliminating the drug peddlers and mafia operating not only in Punjab, but also in other parts of the country”.

The proposal led to questions on practicality as well as law. First, it is estimated that about 15,000 drug peddlers and addicts are in the state’s jails either as convicts or undertrials. More are likely to join their company given the crackdown ordered by the state government. Even if half of these get convicted and sentenced to death, the government is certainly going to have a gigantic task on hand to hang them in case the proposal gets the clearance of the Union home ministry and the courts.

While it appears impractical, a Bombay High Court ruling had already described as unconstitutional an amendment introduced in 2001 providing for the death penalty for repeat offenders under the NDPS Act. Subsequently, the Act was amended in 2014 to remove the provision for the death penalty. An amendment to the Act would need the concurrence of the central government and only if the ruling party agrees to the proposal that an amendment be brought about. This is quite unlikely in the present circumstances. Besides, the amendments would again go in for judicial review. Thus, the announcement by the Amarinder Singh government is being seen as another gimmick.

The recommendations to the centre were followed up by another quirky decision. The chief minister announced that all the 3.5 lakh-odd government employees would have to undergo a dope test. Also, a dope test would be conducted before all appointments and promotions.

The move was announced even though there was no demand or need for such tests which cost about Rs 1,500 per person. The government did not think twice before announcing expenditure of crores of rupees on such tests which are unlikely to yield any impeachable evidence about drug addicts.

Dope tests, which are generally conducted on sportspersons or on suspects to gather evidence, don’t give accurate information about addicts. For instance, anyone consuming cough drops can test positive while a person who may be an opium addict but has not taken it for a few days may test negative.

Besides, the very basis of conducting such tests makes little sense. True, some police personnel are known to be drug addicts and all those suspected could be put through such tests. Also, it reflects poorly on superiors who are not aware of subordinates taking drugs.

The proposal in fact turned farcical when some of the opposition leaders sought such dope tests for ministers and even the chief minister. Some of the opposition members volunteered to undergo the test. A Punjab minister went to a government clinic to get himself tested and advised all his cabinet colleagues to do the same. Thus, instead of yielding any results, the proposal became a mockery of sorts.

Even as the people were coming to terms with such proposals to tackle the menace, the government announced a ban on selling syringes without prescription from doctors. Apparently, the idea was to choke the supply of such syringes for drug addicts but it led to a hue and cry by patients including medics and those suffering from acute diabetics. This forced the government to withdraw the order.

All this evidences a poor and unplanned strategy to tackle the menace. It may surprise many that the state does not have any comprehensive study on the extent of the problem.

Estimates vary from 20 percent to 70 percent of youth being within the stranglehold of drugs. A huge controversy was kicked off a couple of years ago following a statement by now Congress President Rahul Gandhi, who said 70 percent of the youth were addicted to drugs in the state.

The fact is that he was mistaken as the study to which he had referred had merely said that “70 percent of all drug addicts in the state were youth”. The Shiromani Akali Dal, meanwhile, has been saying that the claims of drug addiction were too exaggerated and that just about two percent of youth are addicts. Again, these figures were from a story about patients visiting a particular hospital in Delhi. The figure of two percent was of the addicts among all the patients visiting that hospital. Former Deputy Chief Minister Sukhbir Singh Badal even went to the extent of declaring that there was an effort to “defame” the state and its youth. As an opposition leader, now he is trying to corner the government for its failure to curb the menace.

There is no denying the fact that drug addiction is a serious problem in Punjab and concerted efforts must be made to draw up a comprehensive strategy. For that the government must involve experts, eminent citizens, NGOs, social groups, educational institutions and public representatives like legislators, municipal corporation and committee members and sarpanchs and panchs. It must also involve psychologists and trained counsellors to weed out the menace.

A legal aspect that the government must keep in mind is to ensure proper investigation and prosecution of drug peddlers. The point was brought home to the chief minister by a judge of the Punjab and Haryana High Court when Capt Singh attended her court in connection with an election petition.

Justice Daya Chaudhary took the opportunity of the presence of the chief minister to point out the police failure in implementing the NDPS Act. She said there were instances when the crucial forensic report was not submitted in such cases along with the final inquiry reports. This leads to weakening of the cases and even acquittals. She also pointed out that several false cases and instances of “implanting” drugs had come to the fore in recent times. She asked him to ensure strict implementation of the Act.

A peevish chief minister could only assure the court that he would personally look into such cases.