Above: A young kidney patient undergoing dialysis, which helps to purify the blood

While people with clout can get Kidney for transplant within days, commoners run from pillar to post as a complex medical and legal system and high demand leave them by the wayside

~By Usha Rani Das

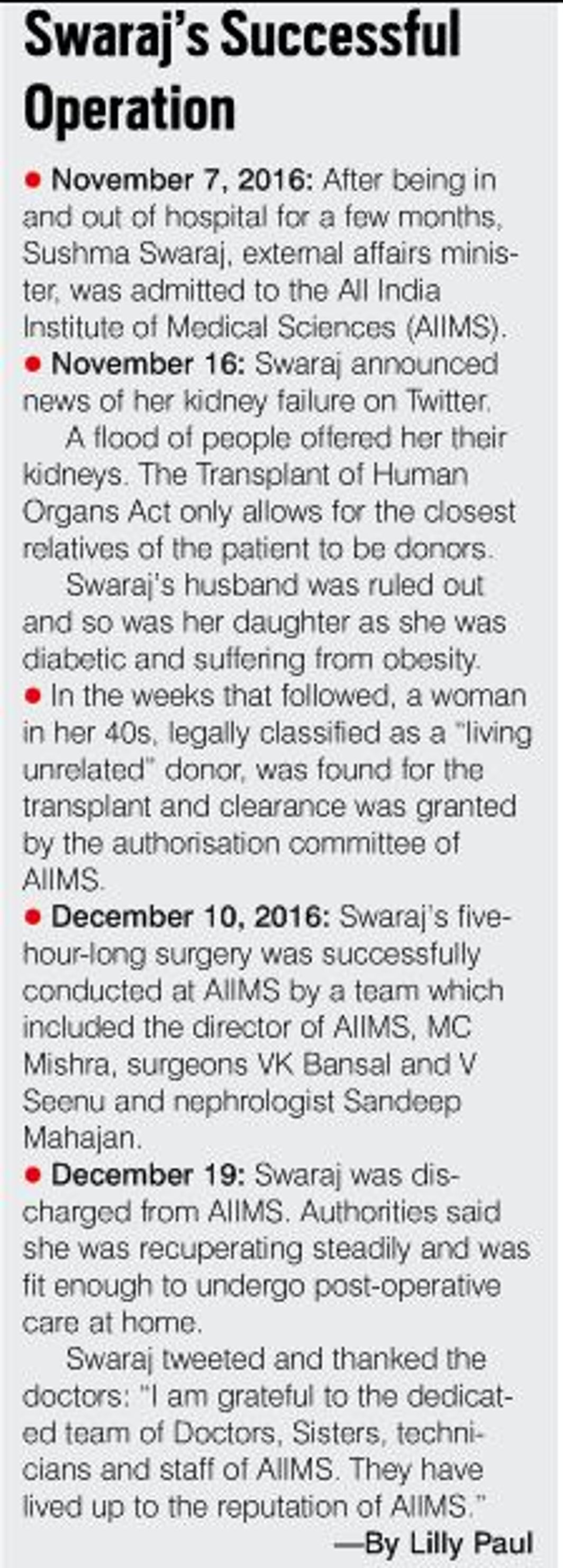

In a country where donor kidneys are in short supply, some questions are often asked. One of them is whether Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, who was recently admitted to AIIMS for a kidney transplant, would have to undergo the same procedure as the rest of the country under the Transplant of Human Organs and Tissue Rules, 2014.

There was a precedent—in 2016, Minister of External Affairs Sushma Swaraj got a kidney within a matter of weeks (see box). She was admitted to AIIMS on November 7, 2016, and her surgery was performed successfully on December 10. More curious was the fact that there were no related donors, which, according to the Act, could be a spouse, mother, father, daughter, son, grandmother or grandfather. A distant relative, legally classified as an unrelated donor, came to her rescue.

While people with clout have to wait for just a few days for a kidney, it can take weeks, even years, for a commoner to get legal clearances in this regard. Are the laws different for the powerful and for commoners in India?

TRAUMATIC LIFE

Just as Jaitley announced the news of his illness on Twitter, one Sunanda Brahma, who has been on dialysis for over four years, took to Facebook to reveal her struggle. She said in her post: “Today I feel that once again my nose has been rubbed in the ground and I have been told that we live in a country where we do not have an equal right to live and that there are different strokes for different folks.” A few months after her kidney failed, an unrelated donor from a weaker section of society offered her a kidney. In return, Brahma had to look after the education of the donor’s children. Her application was rejected. And now, due to complications, she is not eligible for a cadaver organ (from a brain-dead person) either. “My point here is that how do people like Sushma Swaraj and Arun Jaitley go through transplant surgeries in a week’s time with unrelated donor kidneys arranged, doctors ready and waiting to do the surgeries, authorities giving clearances overnight?” she posted.

Supreme Court advocate Mahendra Kumar Bajpai told India Legal: “It is not that everyone jumps the queue. There is a national roster and very stringent laws. The ones who have got the kidneys are ultimately ministers. Let them have that privilege. I am not aware of the procedure that they went through. However, the Act is good. The problem is with the implementation.”

Supreme Court advocate Mahendra Kumar Bajpai told India Legal: “It is not that everyone jumps the queue. There is a national roster and very stringent laws. The ones who have got the kidneys are ultimately ministers. Let them have that privilege. I am not aware of the procedure that they went through. However, the Act is good. The problem is with the implementation.”

The Act states: “Living donors are classified as either a near relative or a non-related donor. A near-relative (spouse, children, grandchildren, siblings, parents and grandparents) needs permission of the doctor in-charge of the transplant centre to donate his organ. A non-related donor needs permission of an Authorisation Committee established by the state to donate his organs.”

The authorisation committee’s work is to ensure that there is no commercial intent in the donation. A non-relative donor can be considered only if one is willing to offer a kidney out of “affection and attachment” to the donee, and not for money. It is because of this provision that unrelated donations are viewed with suspicion.

DIFFERENT RULES

While surgery for a kidney transplant from a related donor is cleared at the hospital level, that involving an unrelated donor requires clearance at the state level. Each state has its own rules and these range from seniority on the waiting list to complex calculations that take into account the severity of the disease.

The authorisation committee, formed under the Act, checks the background and the relation of the unrelated donor to the recipient. It also has to check the socio-economic background to ensure that the procedure is not taking place for monetary compensation. It even checks the donor’s income tax returns. If the donor is from a state other than the one where the surgery is being performed, one needs a clearance from the donor’s home state authorisation committee too.

Dr Sunil Shroff, managing trustee of Mohan Foundation, a Chennai-based non-profit organisation, wrote in a newsletter that the section that allows unrelated donors is often abused. He stated: “Many a time, the authorisation committee will overlook such cases sometimes sympathising with the recipient and clearance is given in what is clearly likely to lead to commercial transaction.”

Dr Yatin Mehta, president of the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine, said that though the Act is stringent, there is gross misutilisation of resources which extends the suffering of patients. He told India Legal: “When someone is brain-dead, the doctors can disconnect the ventilator only after the family gives consent for organ donation. You cannot disconnect it if the family disagrees. This is misutilisation of resources. It is a flaw of the system. Secondly, the act refers to living will. That means one can make a will while alive stating that one wishes to donate organs after death. In that case also, the hospital has to have a committee and it has to involve the local magistrate. You still have to go through the court to certify that this person wishes to donate his organs. They have made the system very complicated.”

COMPLICATED PROCESS

Naresh Singhania has been on dialysis for five years now. He told India Legal: “My family started the paperwork in June 2015. After four months of struggle, we got the clearance for a kidney transplant from a related donor. If a related donation takes this much time, imagine how long it will take for an unrelated one.”

In another case, Mumbai-based lawyer Nitin Vhaskar was granted permission by the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO), the central government body in charge of the country’s deceased donor transplant programme, to bypass the waiting list for a kidney in 2016. A dialysis patient, Vhaskar was approached by organ donation counsellors when his brother, Sandeep, was declared brain-dead. He consented on the condition that he receive one of the kidneys. The matter immediately came up before the Zonal Transplant Coordination Committee in Mumbai who approached NOTTO for advice. It was past midnight when the organisation called and granted permission for the allocation and the transplant was carried out.

The complexities of the system have sometimes forced people to approach high courts. Forty-six-year-old DK Ravikumar’s application was rejected by the health and family welfare department on the ground that he had failed to establish the relationship between the donor and donee, and hence there was a commercial motive between them.

Ravikumar, a farmer from a village in Maddur taluk of Mandya district, Karnataka, was afflicted with dengue in 2013. The medication given for its treatment resulted in both his kidneys failing and he was advised to get a renal transplant. However, when he found a donor, his application was rejected by the authorisation committee on the suspicion that the donor was doing it for money. Ravikumar then moved the Delhi High Court in January 2018 against this order and asked the Court to grant permission for a kidney transplant. The Court established that the donor knew the donee well and asked the health department to grant permission on April 18.

While Vhaskar and Ravikumar were lucky, Nahid Anwar lost her husband in 2017 though his name was included in the hospital’s list for kidney transplant a year earlier. And there is the well-known case of former Maharashtra Chief Minister and Union Minister Vilasrao Deshmukh who died of multiple organ failure in Global Hospital in Chennai in 2012. A delay in harvesting and transplanting an organ led to his death.

“Had we got a liver, he would have had a chance. Last night, a brain-dead donor died before we could transplant. Three donors were available today, but it was too late,” Dr K Ravindranath, chairman of the Global Hospital Group, told NDTV.

HIGH DEMAND

And that is the main problem in kidney donation—the abysmally low rate of donation in India. Nearly 2,20,000 people await kidney transplants at any given time in India, of whom only 15,000 end up receiving a kidney. Over five lakh people die annually, waiting for a transplant, despite their name being on the waiting list. The rate of 0.5 donors per 10 lakh people in India is one of the lowest globally.

Bajpai said it is because of how people perceive organ donation in the country. He said: “They somewhere connect it with kidney trade. There have been instances where the doctors have declared patients brain-dead even though they aren’t as they want to sell the organs. This creates distrust in the system and hence, people often don’t donate organs.”

Growing anomalies in the system make the situation worse. On April 17, 2018, Goa Health Minister Vishwajit Rane ordered an inquiry into the transfer of a brain-dead man’s organs which had been harvested at a private hospital in Goa to Mumbai instead of being donated to a patient waiting for transplant at Goa Medical College and Hos-pital (GMCH) nearby. Dr Astrid Lobo Gajiwala, the director of the Regional Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization, Western Region, Mumbai, wrote a letter to Goa’s health services director, Dr Sanjiv Dalvi, over the need to set up a State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (SOTTO). He stated that without SOTTO, the state does not have the approved list of kidney patients waiting for transplants. The state also does not have an emergency cross-matching facility.

In a similar incident, suspicions arose when Tamil Nadu politician V Sasikala’s husband, M Natarajan, underwent dual organ transplant for his kidney and liver from an unrelated donor who was airlifted from Thanjavur to Chennai. The donor, N Karthik, 19, suffered severe head injuries and was admitted to a government hospital in Thanjavur. Later in the night, he was airlifted to the hospital in Chennai where Natarajan was admitted. Karthik was declared brain-dead. The incident raised several questions from political parties and doctors—if Sasikala jumped the queue, how could the family of Karthik, who earned a living putting up banners of political parties, afford to airlift him? Was this a case of commercial donation?

SINGAPORE BECOMES A HUB

In countries like Singapore, Australia and Iran, financial compensation for living organ donors is legal. Hence, the demand and supply are almost on a par. Samajwadi Party leader Amar Singh got his kidney transplant procedure done at Mount Elizabeth Hospital and Medical Centre in Singapore in 2009. Reports stated that an unidentified party worker close to him was the donor.

Experts in India do not support monetary exchange as they think it might increase the illegal trade in the country. Bajpai said: “This will become a business just like the exploitation of surrogate mothers in India.” But the matter has come up for discussions. In April 2018, two petitions came up for hearing in the Punjab and Haryana High Court in which one of the questions considered was whether organ do-nation for monetary consideration can be carried out under a regulated system to reduce mortality.

Experts say cadaver donations will ameliorate the situation. Shroff told India Legal: “Even in kidney transplant, this option is viable. In the US and UK, 80 percent of donations are cadaver organs, while in India it is only 20 percent. There is a real shortage of donors here. There is also lack of awareness among doctors and the public. Some-times, consent is an issue, sometimes maintaining the donor is an issue and sometimes, identifying the right donor.”

According to Mohan Foundation, approximately 7,500 kidneys, 2,000 livers and 100 hearts are transplanted every year in India. And only 15 percent of kidney transplants are cadaver transplants. Most of the 720 kidney transplants from brain-dead donors in India in 2014 took place in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Maharashtra and Karnataka. This is a fraction of the 3,000 to 6,000 kidney transplants in India that year. Mehta said: “All the cadaver organs were utilised. In Europe, they hardly do related donor transplant. Hence, the chances of survival are better there than in India.”

While hundreds have made it to the waiting list and thousands more have to be registered, there are many who will die before they can disengage themselves from the complexities of the system.

Comments are closed.