In order to resolve the manpower crisis in the healthcare sector, the government will need to greatly invest in modern facilities so that doctors and nurses are attracted to work in rural India

~By Kamal Kumar Mahawar

It seems that the matter of overburdened junior doctors in government hospitals is finally gaining traction with the Delhi High Court asking the centre some probing questions regarding staffing levels and the doctor-patient ratio.

This ratio is a commonly used metric to measure the number of doctors relative to the population in any given country. The number of “allopathic” doctors per 1,000 people stands at a meagre 0.61 in India as compared to 2.554 in the US and 2.806 in the UK. The actual number of qualified MBBS doctors working is likely to be even lower as some of them may have retired and there is no shortage of people who like to call themselves doctors. Not just Ayush practitioners, but registered medical practitioners (RMPs) and even quacks insist on using the tag of doctors. And as creating doctors is a time-consuming and expensive undertaking, the government is systematically encouraging this behaviour. After all, it is systematically promoting Ayush professionals as modern doctors and creating RMPs.

Though the Medical Council of India is entrusted with the job of maintaining an accurate medical register, the state of its database is such that it doesn’t even know whether the doctors on it are alive or dead, let alone practising or not, and if practising, in which part of the country and in what speciality.

WOEFULLY LACKING

Currently, we have approximately 63,835 medical seats in 426 MBBS colleges. Even if all these students were to work as doctors in India upon getting qualified, it will take several decades to reach the doctor-population ratios currently seen in developed countries. But simply creating more doctors without a comprehensive investment in the healthcare infrastructure is not likely to solve the problem. Doctors need clinics, diagnostics, hospitals, nurses, paramedical staff and a whole range of modern equipment to deliver 21st-century healthcare. For far too long, we in India have only focused on creating doctors without a comprehensive plan to address the issues facing our healthcare. The end result has been a totally unplanned urban mushrooming of private clinics and nursing homes competing with each other, often unethically, for a small section of population which can afford them. This has also created a relative vacuum of facilities for the urban poor and rural populations.

Yes, we need more doctors, but it is also a fact that we are not able to employ even the doctors that we create in adequate facilities that are fit for the purpose. It is worth examining here the options available to doctors who pass out of college today. They can either work for the public sector for meagre wages or start an independent practice in the cut-throat and unprincipled private world. Given the state of our public sector, most prefer the latter even if the journey is arduous in the beginning. This is the reason why even institutes such as AIIMS are now struggling to recruit faculty.

There is another option, which many graduates ultimately resort to and that is to emigrate abroad. Western countries can employ more junior doctors than their own systems can create, whereas we are not able to offer postgraduate training places to all our qualified doctors. It is a sad reality that a large number of our medical graduates are left to fend for themselves when it comes to obtaining post-qualification training. No developed country allows a fresh MBBS graduate to work independently, but in India, this is not only allowed but encouraged.

DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

How are developed countries then able to employ four times the doctors per unit population? The answer is simple. Those countries have modern healthcare facilities for most of their population, including those who live in remote locations. Building medical facilities across the length and the breadth of the country for the urban poor and rural populations is not going to be easy. It will need significant planning, support and vigilance from the state, the involvement of the insurance industry, contributions from the charitable sector and newer, more affordable models of care from the private sector to cater to the lower middle classes. As far as the poor in the society are concerned, they will continue to rely on the public sector.

It is estimated that approximately 80 percent of Indian doctors work in urban areas catering to approximately 28 percent of the population. This leaves 20 percent of doctors for the rest of the population. The situation is even more alarming if you consider the almost complete lack of specialisation among rural doctors and that the nearest in-patient facility in many areas can be several kilometres away. In remote areas, there is sometimes one doctor for tens of thousands of people. It is not too difficult to understand how we have reached this state.

Our governments have successively failed to invest adequately in health. Poor management, misplaced priorities in the name of a number of short-sighted schemes, and often, blatant corruption have meant that our public healthcare infrastructure is probably one of the worst in the world. In a recent report, India was ranked 154 out of 195 countries on healthcare index, even below Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

PRIVATE HEALTHCARE

In urban India, we at least have some healthcare, which is, of course, largely by the private sector. But private healthcare is funded out of patients’ pockets and rural India simply does not have deep pockets to enable the building of hospitals and clinics by the private sector. And as the economic condition of rural India is unlikely to improve dramatically in the near future, any attempt to improve the healthcare of this section will have to be funded by the state.

Costs of healthcare

The costs of healthcare between India and the UK cannot be compared. While one is a developing country, the other is a rich one, with different input costs. Though public healthcare in India is hugely subsidised, in the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) is completely free at the point of delivery. The British government funds NHS through taxes.

UK spends approximately 9 percent of its GDP on healthcare, compared to 1.4 percent by India. Almost 80 percent of UK’s healthcare is public, whereas approximately 80 percent of healthcare in India is private. The Indian government cannot be expected to fund health like the UK. Our country has a population of 1.3 billion compared to UK’s 65 million. So the comparisons in healthcare are unfair. Also, private healthcare in India has no fixed tariff, when in the UK, it is a very small percentage of the system.

It will need a massive investment to build modern facilities that are fit for the 21st-century and then to attract doctors and nurses to work in rural India. The government should concentrate its resources and efforts on this section of society. If financial incentives can drag a doctor or a nurse to work in a remote corner of Saudi Arabia, surely the same incentives can get people to work in villages in their own country. The sooner our government stops banking on the altruism of doctors and nurses to improve our healthcare scenario, the easier it will be for them to resolve the current manpower crisis.

The ratio is further skewed if you look at public sector hospitals. With widening pay gap between the private and the public sector, and the alarming state of infrastructure of the latter, not many young doctors aspire to work in these hospitals anymore. This means that our public hospitals rarely have enough faculty members to provide quality care to the ever-increasing pool of patients and to give worthwhile training to resident doctors.

RESIDENT DOCTORS

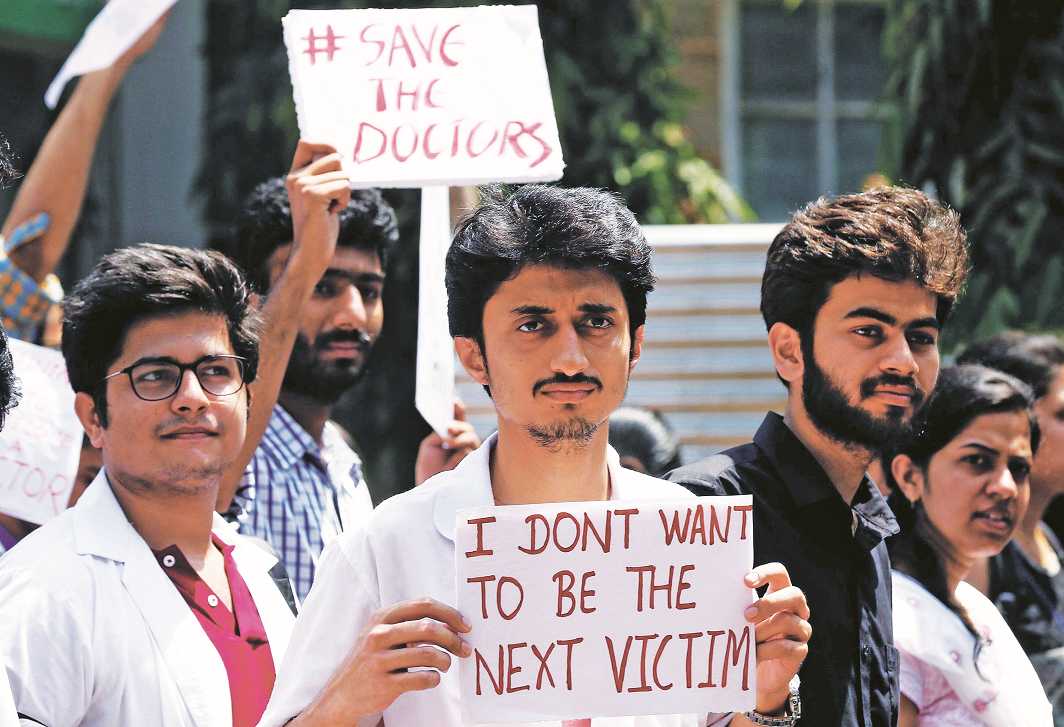

It is no secret, and this is true across the world, that most of the day-to-day work in any public hospital is carried out by junior (resident) doctors and nurses, while faculty members concentrate their efforts on major treatment decisions, technically challenging tasks, education, training and research. But the problem in our state hospitals is unparalleled because of the sheer workload a resident doctor faces. Typically, these doctors are overworked and underpaid, all in the name of so-called training, which itself is severely deficient in many areas and in radical need of reformation. How can you obtain effective education and training when you are simply crumbling under the weight of day-to-day work? These doctors sometimes work inhuman hours in an unsupervised environment and as their careers are directly dependent on the goodwill of the faculty members, they rarely feel empowered to raise their voices about any concerns. Anonymous surveys that developed countries have to understand the plight of junior doctors do not exist in India. And this is where things have reached a tipping point. These overworked, under-rewarded doctors working in ill-managed and badly resourced hospitals simply cannot deliver what patients expect of them. Though this is not the only reason for violence against doctors in India, this is one of the most important ones.

Modern healthcare delivered by qualified, well-trained doctors is not going to come cheap. Though creating more doctors is the necessary first step, we have to do a lot more to train and retain that valuable resource. The government approach to healthcare planning in India seems fragmented at best and almost completely devoid of a coherent strategy.