Above: The Udaipur mandi stocked with forest produce

With forest produce being notified as a tradable commodity and restrictions being removed, Rajasthan’s tribals can finally get benefits from flowers, nuts and berries nurtured by them

~By Vivian Fernandes

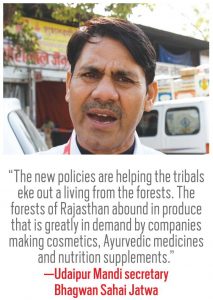

A visit to the new market yard of Udaipur mandi yields some gems. There is a heap of wild Indian gooseberry (amla) selling for Rs 90 a kg. The wholesale price of cultivated amla in Delhi during that week was around Rs 15. Nearby is a heap of puhad or wild senna, which fetches around Rs 10 a kg. It is said to be an immunity booster and has export markets in China, Vietnam, South Korea and Germany. Mandi secretary Bhagwan Sahai Jatwa said its price had shot up to Rs 65 a kg last year because of hoarding, which made the importers turn to Africa.

There are other heaps of the fruits and flowers of India—butter tree (mahua), wild soapnut (ritha) and jatropha (rattanjot).

At the old mandi, a trader had safed musli, a sex stimulant retailing for Rs 2,500 a kg. Meanwhile, the owner of Metro Trading Company displayed a handful of seeds of black oil plant (mal kangni) which fetches Rs 250 a kg.

Collectively called minor forest produce or non-timber forest produce, these had gone under-harvested, depriving tribals of employment and income.

New policies are helping the tribals eke out a living from the forests. Jatwa says the forests of Rajasthan abound in such produce which is greatly in demand by companies making cosmetics, Ayurvedic medicines and nutrition supplements. The government’s policies have helped too. For example, the policy of coating urea fertiliser with neem oil for slow release to plants and to prevent misuse has brought companies like Gujarat Narmada Fertiliser Corporation to the mandi with an order of 5,000 tonnes.

TRADABLE COMMODITY

In October 2015, these forest products were made tradable in Rajasthan’s regulated mandis. But they still needed transit permits from the forest department to be transported and traded. These were rarely issued. Though they cost just Re 1 each, the process of obtaining them was tedious. Even to move a small quantity of wild produce from the forests, one had to apply to the ranger who would send a guard to the location to physically verify the stuff. The district forest officer would then issue the permit.

Jatwa said violation of the permit resulted in confiscation of the seized material, a stiff penalty and even a jail term of six months. Tribals were thus deprived of endowments, which was theirs by right. Instead, the state would sell the right to procure and sell the produce.

Jatwa showed an annual contract of 2012 which gave the contractor the right over the produce of the forests in Saira village panchayat in Udaipur’s Gogunda tehsil. It was for Rs 12,500. Contractors, he said, had no obligation to buy at all, but tribals could only sell to them at a price they fixed. It was unfair.

With forest produce being notified as a tradable commodity, wild produce worth Rs 189 cr has been sold at the mandi in the past two years. The mandi provides meals to sellers at Rs 5 each.

But things have changed now. Transit permits have been abolished in Rajasthan’s forest districts but there are still complaints about police and forest officials extorting money from tribals and drivers who did not have them. Even now, tribals come at break of day to avoid harassment by officials, Jatwa said. Not many are aware that there is no need for transit permits.

TRIBAL POWER

The new market yard is yet to be operational. The space for shops will be allotted in a month. There will be 71 of them. A few will be reserved for tribals, some for industries processing wild produce, others for big exporters and a few for state-level tribal cooperatives.

There was resentment among the traders, some of whom accused the officials of being corrupt. The officials, in turn, said they were angry at not being allowed to apply for multiple shops for themselves and their kin.

There was resentment among the traders, some of whom accused the officials of being corrupt. The officials, in turn, said they were angry at not being allowed to apply for multiple shops for themselves and their kin.

Jatwa’s enthusiasm was palpable. It was obvious that it was at his initiative that forest produce had been notified as a tradable commodity. In two years, wild produce worth Rs 189 crore had been sold at the mandi, he said. Commission agents can charge 2 percent of the value from buyers. The mandi levies a tax of 1.6 percent. It provides meals to sellers at Rs 5 each. To the kin of tribals and farmers who die in accidents on the way to or from the mandi or from snake bites, a compensation of Rs 2 lakh is given. In three years, the mandi has distributed Rs 3.80 crore in death relief.

The removal of restrictions on trading has brought more produce to the market. With more players, there will be better price discovery. Newer uses will also be found.

At a camp in Devla recently, tribals met officials of the Rajasthan Medicinal Plants Board. They showed fruit, flowers, nuts, berries and roots that had varied uses such as boosting milk in lactating mothers, curing snakebite or bringing down fever.

Unchecked commerce can be corrosive but for now, it is giving tribals a stake in conservation by putting money in their hands.