Above: Suu Kyi’s stilted response to the tragedy has hit her image. Photo: UNI

Though there was global condemnation of Aung San Suu Kyi’s stilted response to the Rohingya refugee crisis, many forget that she has to work within the constraints of the constitution which gives the army a powerful role to play

~By Colonel R Hariharan

A recent article in The New Yorker titled “What Happened to Myanmar’s Human Rights Icon?” reflects the question haunting admirers of Aung San Suu Kyi. She was seen as the global upholder of universal human rights, but as Myanmar’s de facto president (officially state counsellor) she has failed to live up to their expectations over the Rohingya issue. More than half a million of these ethnic Muslims fled from Rakhine state in Myanmar to seek refuge in Bangladesh to escape military persecution. However, Suu Kyi not only took a month to make an official statement, but it lacked remorse at the horrendous human tragedy being enacted under her watch.

The exodus of Rohingyas started when the army launched large-scale operations after 150 Rohingya insurgents attacked 24 police posts and a military base, killing 12 security personnel on August 25, 2017. In the military operations that followed, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army lost 59 insurgents, over 1,000 Rohingyas were reported killed and many women raped. Human Rights Watch, citing satellite images, said 214 Rohingya villages were completely destroyed.

Bangladesh’s foreign minister AH Mahmood Ali called it a “genocide” waged by Myanmarese troops, while UN Human Rights Commissioner Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein called it “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

DECADES OF CONFLICT

Even if the alleged army atrocities fail to fall under the UN’s definition of genocide, the army probably carried out “ethnic cleansing”. The Rohingyas, considered illegal Bengali settlers, are concentrated in the northern Rakhine state. They have been involved in armed ethnic conflict since Myanmar’s independence in 1948. So the army probably hit upon ethnic cleansing as a “final solution” to rid the country of the unwanted minority.

There is no doubt that Suu Kyi’s stilted response to the human tragedy has affected her image globally. Her charm and personal sacrifices during her long struggle to restore democracy against a ruthless military dictatorship drew admiration the world over. The western world which has been selectively waging “wars” for regime change in many authoritarian countries made her the poster girl for their “cause”. They put her on a pedestal and showered her with honours, including the Nobel Peace Prize. And Suu Kyi was modest to remind her admirers that “she was no saint of any kind”, but only a politician. She added, “politicians are politicians, but I do believe there are honest politicians and I aspire to do that”.

So it is no wonder that when she became the de facto ruler of Myanmar, there were high expectations from her admirers both at home and abroad. They seemed to forget that in addition to being the head of a troubled state, she had a difficult role to play as leader of the ruling National League for Democracy and needed to retain her popular support.

CONSTITUTIONAL LIMITATIONS

However, Asian powers who had their ears to the ground were probably more realistic because Suu Kyi faces multiple problems in functioning as head of state. When the army decided to end its 50-year hold on power, it ensured that the constitution was rewritten by 2008 to give it a legitimate presence in legislature and a role in governance. One-fourth of the seats in parliament are reserved for the army. Also, the army calls the shots on internal and external security issues as the constitution has reserved the posts of three ministers—home, defence and border affairs—for the army.

So Suu Kyi has some deft political tightrope walking to do and functions within the constitutional straitjacket. According to the constitution, she is not eligible to be elected president because she is married to a foreigner. So the position of state counsellor (above the president) was created extra-constitutionally to keep her at the top of the power structure.

So Suu Kyi has some deft political tightrope walking to do and functions within the constitutional straitjacket. According to the constitution, she is not eligible to be elected president because she is married to a foreigner. So the position of state counsellor (above the president) was created extra-constitutionally to keep her at the top of the power structure.

Myanmar has been facing an existential struggle against approximately 16 ethnic insurgencies since independence. This has justified the army’s tight grip over three vital ministries dealing with national security. Unless the insurgency groups give up arms and join the political mainstream, the army cannot be weaned away from its stranglehold on power. So Suu Kyi’s top priority has been to negotiate permanent peace with the insurgent groups. She had organised the 21st Century Panglong Conference, a peace meet, with insurgent groups in August 2016. During the second meeting in May 2017, there was some breakthrough. However, four insurgent groups, particularly the Kachin Independence Army and Arakan Army (a Rakhine-based group), did not join the process. So, it continues to be a work in progress.

Suu Kyi probably knows the Rohingya issue will be a test of her leadership skills. However, her actions will always be conditioned by the army’s control over the three vital ministries. Of course, the army still retains the option to slap martial law and seize power again. So she cannot take any action that could be construed as a provocation by the army, which is watching her with a wary eye.

ROHINGYA IDENTITY CRISIS

Though Suu Kyi is immensely popular at home, she has to watch out for any popular backlash in handling the Rohingya crisis. Most of the majority population, which is Buddhist, including those who condemn the army’s atrocities against the Rohingyas, do not accept them as part of the national mainstream. Unlike the majority Bamar community, Rohingyas are Muslims and racially different from the people of Myanmar—they are dark and speak a dialect similar to the Bengali spoken in Chittagong.

Officially, the term “Rohingya” does not exist; they are referred to as Bengalis, indicating their illegal immigrant status. They are not listed among the eight officially recognised indigenous ethnic groups, though their presence was tolerated till the army enacted the Burma Citizenship Law in 1982. It laid down 1823 (before the Anglo-Burmese war) as the cut-off year for recognition of eligibility for citizenship. This rendered a million-plus Rohingyas stateless. Unless the citizenship law is suitably amended, it will be difficult to absorb them in the national mainstream.

Suu Kyi’s actions are constrained by the army which has control over three vital ministries and retains the option to slap martial law and seize power again.

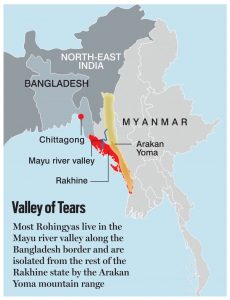

Geographically, their concentrations are in the Mayu river valley along the Bangladesh border and isolated from the rest of Rakhine state by the Arakan Yoma mountain range. So Rohingya habitations have remained backward, untouched by what little development has taken place in the state. Ethnic and religious differences periodically spark Rohingya-Buddhist riots. In 2012 and 2013, these degenerated into anti-Muslim riots and spread to the rest of the country.

TERROR LINKS

After partition of Myanmar, Rohingyas conscious of their distinct identity, wanted their areas of habitation to be merged with East Pakistan. With Pakistan’s support, Rohingya Mujahideen extremists carried out sporadic attacks for the cause for about 10 years from 1950, without much success. In 1970-80, a number of Islamist movements came up. However, the army ruthlessly crushed them. Among them, the Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, which was formed in 1982, developed contacts with Islamist extremist groups linked to the Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

These terrorist links added virulence to the Rohingya insurgency in 2016-17. On October 9, 2016, Rohingya terrorists in large numbers attacked three Myanmar police posts located along the Bangladesh border. They killed nine officials and looted firearms from the posts. Two days later, they again attacked and killed three soldiers. International Crisis Group (ICG), a well-known think-tank, in a report on Rohingya militancy last December said it had interviewed members of Harakah al-Yakin (Faith Movement), a Rohingya militant group in Bangladesh, and they had taken responsibility for the attacks. According to the ICG report, the group had links with Rohingya expatriates in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. It also added that Afghan and Pakistani fighters had secretly trained groups of Rohingya villagers in Rakhine state. Indian intelligence agencies have also accessed similar information, identifying different groups and their leaders.

The Rohingya issue had always been a source of friction between Myanmar and Bangladesh. However, Sheikh Hasina Wajed’s Awami League government has been carrying out intense operations to eradicate jihadi terrorism infesting the country. So Bangladesh is extremely wary of giving asylum to Rohingya refugees flooding the country lest jihadi groups also infiltrate the country. However, due to popular sympathy for the plight of fellow Muslims, Bangladesh is accommodating them within its limited resources with help from international agencies.

INDIA’S ROLE

India also does not want to allow the Rohingyas to cross over, fearing infiltration by terror groups in the sensitive North-east region. Politically, it is untenable for New Delhi to give refuge to them because the ruling BJP won the Assam elections with a promise to cleanse the state of lakhs of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants.

However, as a humanitarian gesture, India is assisting Bangladesh in taking care of over eight lakh Rohingyas there and has allocated Rs 500 crore to Dhaka for this purpose. India also organised 7,000 tons of foodgrain and other basic essentials such as oil and salt for the refugees. The EU, along with Kuwait, is convening a donor conference to collect donations for them. The Pope will also be visiting Bangladesh and Myanmar in November to provide relief to them.

Meanwhile, Suu Kyi had appointed an 11-member advisory commission headed by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan in August 2016 to help resolve the Rohingya issue. The commission’s recommendations for rapprochement include adopting a holistic approach rather than just a military one, dialogue between both communities and creating a solution for citizenship for the Rohingyas.

However, Suu Kyi has to create a climate of confidence for the refugees to return home. To begin with, a credible investigation of the alleged atrocities by the army has to be carried out. Rohingyas living in IDP (internally displaced person) camps in Myanmar have to be extended all assistance to rebuild their shattered lives in their villages. This is the minimum that can be done to trigger the peace process.

Can Suu Kyi pass this acid test? One thing is clear—it will be a long haul before this tragedy is over.

—The writer is a military intelligence specialist on South Asia, associated with the

Chennai Centre for China Studies and the International Law and Strategic Studies Institute.