Above: The third gender need to be recognised as a separate category at the workplace. Photo: Kh Manglembi Devi

The centre has moved to derecognise transgenders in the labour law framework despite a Supreme Court judgment saying they need to be given equal opportunities

~By Venkatasubramanian

In a controversial decision likely to harm the right to privacy of transgender persons, the centre on September 4, decided to drop plans to recognise them as the third gender in the labour law framework. This is according to a recent story which appeared in The Hindu.

That the move flies in the face of a recent Supreme Court landmark judgment elevating the right to privacy as a fundamental right would be of concern to civil society. That the government could take an action violating the express rulings of the Supreme Court in another case, directly dealing with the rights of transgenders, could make it guilty of contempt.

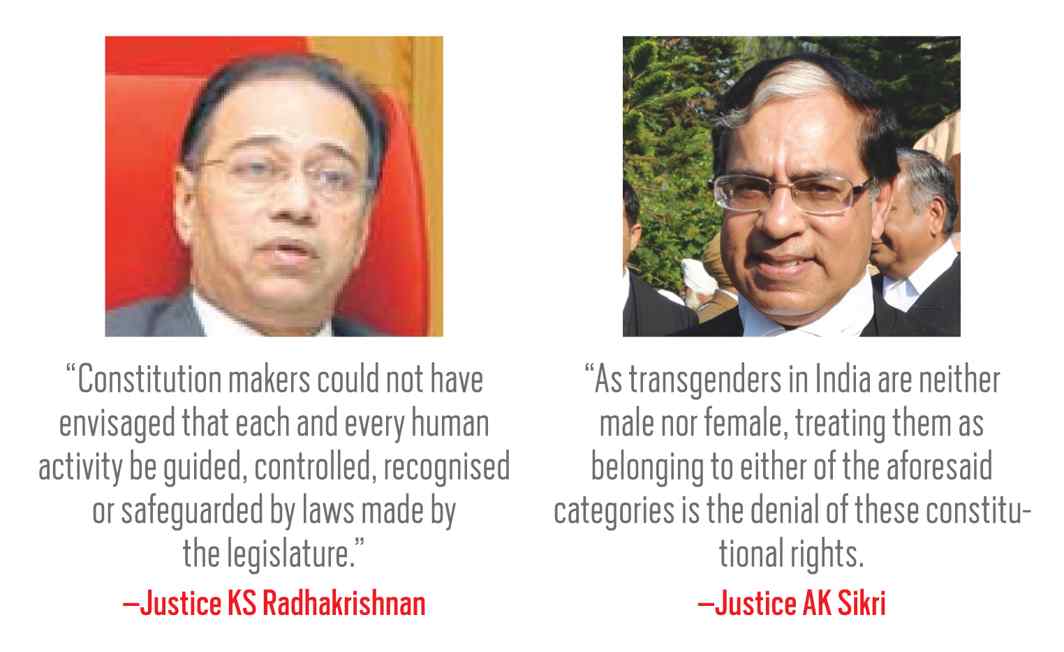

The government’s decision not to recognise transgender persons as the third gender stems from the Union law ministry’s reservations over the General Clauses Act of 1897, according to which “transgenders” fall within the definition of “person”. The labour and employment ministry seems to have accepted the advice of the law ministry to withdraw recognition of transgender persons as third gender without a murmur. This, despite it going against the Supreme Court’s clear judgment in National Legal Services Authority v Union of India, delivered by Justices KS Radhakrishnan and AK Sikri of the Supreme Court, in two separate, but concurring opinions, on April 15, 2014.

While Justice Radhakrishnan has retired, Justice Sikri is still on the bench. Not only does this issue seem to have gone beyond the authority of individual judges who wrote the judgment, it seems to have gone beyond that of the entire court as an institution, whose rulings must be complied with. If the government has any grievance with a decision, the right course for it is to approach the Court and seek clarifications or modifications, rather than unilaterally deciding not to comply with it.

In Paragraph 129 of the judgment, both Justices Radhakrishnan and Sikri declared that hijras, eunuchs be treated as “third gender” for the purpose of safeguarding their rights under Part III of the constitution and the laws made by parliament and the state legislature. The bench, in the same paragraph, upheld the right of transgender persons to decide their self-identified gender and directed the centre and state governments to grant legal recognition of their gender identity such as male, female or third gender.

The bench also held that the centre and state governments should seriously address the problems being faced by hijras/transgenders such as fear, shame, gender dysphoria, social pressure, depression, suicidal tendencies, social stigma, etc. and any insistence for SRS (Sex Reassignment Surgery) for declaring one’s gender is immoral and illegal.  As a consequence of this judgment, the centre initially proposed inserting clauses for recognising the rights of transgender workers in all the four labour codes—wages, industrial relations, social security and occupational safety, health and working conditions—being framed to rationalise the 38 Labour Acts. The codification of labour laws is aimed to remove the multiplicity of definitions and authorities leading to ease of compliance without compromising wage security and social security to workers.

As a consequence of this judgment, the centre initially proposed inserting clauses for recognising the rights of transgender workers in all the four labour codes—wages, industrial relations, social security and occupational safety, health and working conditions—being framed to rationalise the 38 Labour Acts. The codification of labour laws is aimed to remove the multiplicity of definitions and authorities leading to ease of compliance without compromising wage security and social security to workers.

Following the reservations of the law ministry, the labour ministry has now decided not to mention the term “transgender” while stating the entitlements related to gender in any of the labour laws. The draft Labour Code on Wages Bill, prepared by the ministry in 2015, had provisions prohibiting discrimination against transgender persons in the payment of wages.

The report in The Hindu pointed out that the government had proposed special protections for transgender workers in the Factories Act, 1948, too. Equal right to work opportunities in a factory, ensuring respect for inherent dignity, non-discrimination, full and effective participation and inclusion in society, respect for difference and acceptance of transgender persons as part of human diversity and humanity are facets of this special protection. Unfortunately, the law ministry’s advice meant that even this reform of the Factories Act had to yield to the compulsions of technicality, resulting from the purported non-compliance with the General Clauses Act.

With 48 percent of transgenders either working or available for work (as against 23.7 percent females and 75 percent males), their quest against non-discrimination at the work place needs to be given legal recognition in terms of the Supreme Court’s judgments in NALSA and privacy cases.

Transgender activists are of the view that subsuming transgender persons in “persons” is not the remedy which could fulfill their aspirations. Recognition of the third gender as a separate category, they point out, is more than mere symbolism. It helps to recognise discrimination which transgender people face in the job market. Transgender persons at work have certain distinct rights such as the right to undergo a gender affirmation surgery by taking leave if they need to. But job insecurity limits their options to do so, it is claimed.

In his NALSA judgment, Justice Radhakrishnan emphasised the need to take a position on the legal recognition of gender identity of hijras/transgenders in consultation with them and other key stakeholders. Getting legal recognition and avoiding ambiguities in the current procedures that issue identity documents to hijras/transgenders are required as they are connected to basic civil rights such as access to health and public services, right to vote, right to contest elections, right to education, inheritance rights, and marriage and child adoption, he wrote. He also underlined the need to reduce the stigma towards them through mass media awareness, focused training and sensitization for police and healthcare providers.

It is difficult to believe that the Supreme Court in the NALSA judgment could have been unaware of the silence of the General Clauses Act on transgender persons as a third gender. Justice Radhakrishnan explained: “Constitution makers could not have envisaged that each and every human activity be guided, controlled, recognised or safeguarded by laws made by the legislature. Article 21 has been incorporated to safeguard those rights and a constitutional court cannot be a mute spectator when those rights are violated, but is expected to safeguard those rights knowing the pulse and feeling of that community, though a minority, especially when their rights have gained universal recognition and acceptance.”

Justice Radhakrishnan made it clear that the state cannot prohibit, restrict or interfere with a transgender’s expression of personality. The denial of recognition as a third gender to transgender persons is therefore a serious violation of the Supreme Court’s judgment.

Recognition of one’s gender identity lies at the heart of the fundamental right to dignity, and legal recognition of this is part of the right to dignity and freedom guaranteed under our constitution, the Supreme Court held in NALSA. The Court added that non-recognition of their identity in various legislations denies them equal protection of law and they face widespread discrimination.

Justice Sikri was more emphatic, in his separate judgment: “As TGs in India are neither male nor female, treating them as belonging to either of the aforesaid categories, is the denial of these constitutional rights. It is the denial of social justice which, in turn, has the effect of denying political and economic justice.”

By recognising transgenders as third gender, the Court is not only upholding the rule of law, but also advancing justice to the class so far deprived of their legitimate natural and constitutional rights, Justice Sikri wrote.