India Legal: The law minister’s relentless pressure on the judiciary to change the process of judicial appointment seems pressure politics. Is this a two-way street? How does the judiciary deal with it?

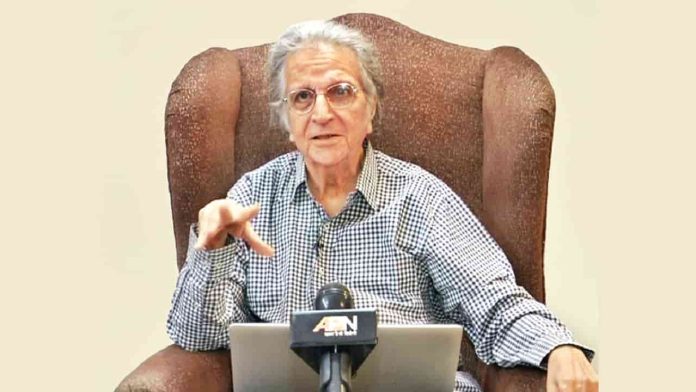

Prof Upendra Baxi: In one of my books, I have distinguished between constitutional politics and power politics. They are two different things. One is interested in the outcome, the other is disinterested in the outcome, but interested in the principles on which matters are decided. Constitutional politics is the politics of principle by which certain words will be interpreted or the text of the Constitution will be interpreted. It is not a competition for political power. I say the Supreme Court does play politics, but plays the politics of interpretation and politics of principles. Not politics understood in the everyday sense of patronage and power. Which is not bad. Democracy needs competitive politics.

Also read: “If the judicial system fails, the whole democratic system fails”

Justice Chandrachud himself said in the Arnab Goswami case that “dissent is the life blood of democracy”. Disagreement is inbuilt in politics. But constitutional politics is a different ball game. It doesn’t need election results. It is interested in democracy, in principles, from which the idea of elections springs forth. The immediate concern is what constitutional principles should be adopted to ensure that the Constitution survives politics.

Also read:“Indian Constitution and Indian democracy are absolutely unshakable”

IL: On many occasions, the collegium was seen as a divided house on judges’ candidature. Internal dissent of appointment adds fuel to the fire against the collegium system. What are the challenges for chief justice Chandrachud in this regard?

PB: Dissent is about disagreement amongst member judges of the collegium on issues like appointment and transfer of judges, memorandum of procedure, etc. These cracks appear all the time. I don’t think anywhere in the world you can make the appointment process transparent. There is no way you can avoid a difference of opinion for appointment in high places. I have experienced it as vice-chancellor of Delhi University.

Also read:“Secrecy essential in Collegium discussions”

Talking of the collegium, I firmly believe that the people of India will never know how judges are appointed, whether by the executive or by the judiciary. Since prime minister Nehru’s time, till the Judges Case, for 40 years, judges were appointed by the executive, by the prime minister, law minister, president. Today, we don’t know how judges are appointed or transferred. There is no risk of democratic knowledge entering judicial appointments. When a chief justice is to retire, he proposes the name of the senior-most judge as his successor. This is the convention. Outside the convention, there is some room for play for both the collegiums and the executive.