By Sanjay Raman Sinha

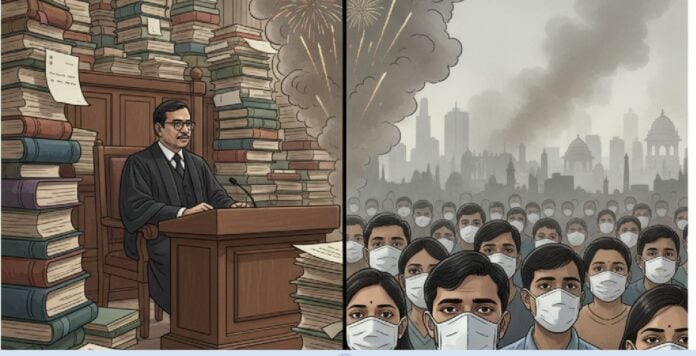

Post-Diwali, as dense smog enveloped the National Capital Region, questions were raised about the Supreme Court’s wisdom in permitting the limited sale and use of green firecrackers. The bench of Chief Justice of India (CJI) BR Gavai and Justice KV Chandran, ruling under the long-running MC Mehta plea, chose a middle path—one that sought balance between festive freedom and environmental protection.

The CJI observed that “firecrackers are an expression of the festive spirit embedded in India’s cultural milieu… however, they must be permitted in moderation without compromising environmental concerns.” His words reflected a nuanced stance—yet critics read the relaxation as judicial leniency in the face of popular sentiment. Some even interpreted it as a reaction to the trolling he faced over a previous remark on Lord Vishnu, arguing that social media pressures had intruded into the courtroom.

A BENCH OF CONTRASTS

Justice Gavai’s judicial approach has often been marked by impatience towards polluters and a strong insistence that the right to clean air must not be confined to Delhi’s “elite citizens”. He has repeatedly emphasized that environmental protection cannot be geographically selective—“We can’t have special treatment for Delhi,” he noted.

The bench’s assertive tone extended to the issue of stubble burning, where the CJI advocated criminal proceedings against erring farmers—a sharp departure from the empathetic approach of Justice NV Ramana’s court, which had refrained from punitive measures. Justice Gavai’s “carrot and stick” philosophy represents a new, enforcement-driven phase of the Supreme Court’s pollution jurisprudence.

THE LONG ARC OF POLLUTION JURISPRUDENCE

The apex court’s involvement with Delhi’s pollution crisis dates back to 1984, when environmentalist MC Mehta first approached the Court over vehicular emissions, the Taj Mahal’s degradation, and the pollution of the Ganga and Yamuna. Over four decades, successive benches have crafted a complex legal framework balancing Article 21 (right to life) with Article 25 (freedom of religion) and Article 19(1)(g) (right to livelihood).

In 2018, the apex court banned firecrackers containing barium and other toxic chemicals, but stopped short of a total prohibition. The decision in Arjun Gopal vs Union of India laid the foundation for the “green firecracker” concept. Later, under Justice Ramana, the Court became more interventionist. His bench demanded accountability, often summoning officials to explain policy lapses, and even considered lockdowns to bring down Delhi’s AQI levels.

Justice Ramana’s humanistic tone was evident when he remarked: “We are wearing masks even at home—the situation is very serious.” His bench also refused to blame farmers alone for stubble burning, arguing that the pollution problem was systemic, not sectional.

FROM PERSUASION TO PROSECUTION

In contrast, the Justice Gavai-led bench has shifted towards deterrence. Where Justice Ramana empathized, Justice Gavai enforces. His courtroom has signalled that persuasion has limits and that accountability must include penalties. The polluter, not the government, is now in the dock.

This change in tone reflects the Supreme Court’s evolving environmental conscience—from emotional urgency to procedural firmness. Yet, it also raises the question of judicial consistency: should every new bench reset the nation’s pollution policy?

FAITH, FIRECRACKERS, AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

The firecracker debate remains one of India’s most complex constitutional dilemmas. It pits the right to religion against the right to life, and the right to livelihood of manufacturers against the right to health of millions. Successive judgments have held that religious freedom cannot override public health. CJI Gavai’s recent observations reinforce this hierarchy, noting that “the right to clean air is universal—not an elite privilege for Delhi.”

However, the partial relaxation for green firecrackers also underscores the Court’s pragmatic turn. By acknowledging both cultural sentiment and environmental necessity, the judiciary may have chosen the most politically sustainable—if not ecologically perfect—path forward.

A COURT IN THE SMOG

From Justice Ramana’s empathy to Justice Gavai’s enforcement, the Supreme Court’s role in shaping India’s environmental policy remains pivotal. Yet, as Delhi continues to gasp each winter, one truth endures—judicial orders can only go so far when governments falter and citizens ignore.

The Court has walked a long, smoky road from MC Mehta to Arjun Gopal. The air remains thick, but so does the Court’s resolve. Whether this year’s green light for green firecrackers will clear the air—or merely cloud it further—remains to be seen.