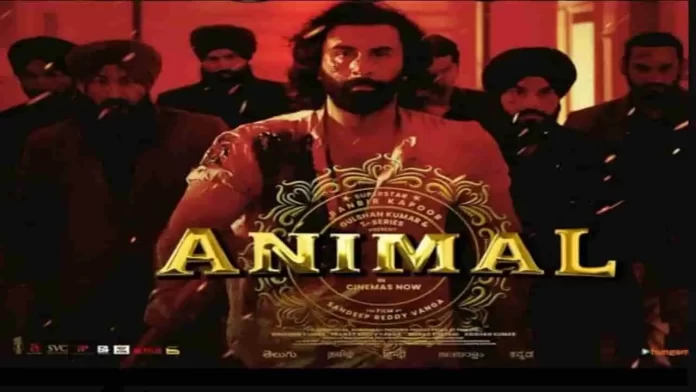

As the Ranbir Kapoor starrer Animal rakes in crores at the box office, questions are being raised about the unbridled violence and misogyny. Has cinematic license become an excuse for wayward filmmaking? How have the courts reacted to such cinematic excess?

By Sanjay Raman Sinha

“Art, morals and law’s manacles on

aesthetics are sensitive subject where

jurisprudence meets other social sciences

and never goes alone to bark and bite…”

—Justice Krishna Iyer

The film Animal is making headlines and money. Sandeep Reddy Vanga’s gory saga has been lapped up by audiences the world over. Within 12 days of its theatrical release, the film has mopped up Rs 750 crore globally with Rs 458 crore coming from its Hindi version in India. A clear sign of the changing taste of cinema audiences. The Ranbir Kapoor starrer is a film that has chosen to push the envelope of cinematic license well beyond the accepted norms of violence and bloodshed. It has also defied hero-stereotypes as well and has indulged in unbridled misogyny, macho masculinity with scant regard for women’s dignity. Does all this make a case for some form of content control? The answer is both yes and no.

Film censorship is a tricky subject. What is acceptable and unacceptable on the silver screen has always been a topic of fiery debate and many court cases have been fought on the issue of film censorship. In India, cinema is regulated by The Cinematograph Act. The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), better known as the censor board, is the nodal regulatory body which was set up by the Act and looks after the certification of films for public exhibition. Though it works under a set of rules much arbitrariness prevails and its “cuts” often escalate in controversies.

Expressing views through films is guaranteed as a fundamental right of expression under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. It states: “All citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression. This implies that all citizens have the right to express their views and opinions freely. This includes not only word of mouth, but also a speech by way of writings, pictures, movies, banners, etc.”

Though movies come under the right to freedom of expression, there are reasonable restrictions enjoined. Film censorship is used to ensure that “public order, health, morality…” is preserved. It is from this provision that film censorship gains its sanction.

In the KA Abbas vs Union of India case of 1970, Chief Justice Hidayatullah, Justices Shelat, Mitter, Vidyialingam and Ray observed that censorship is governed by the standard of reasonable restrictions stipulated in the Article 19(1) of the Constitution.

The film in question was A Tale of Four Cities, or Char Sheher Ek Kahaani which depicted the contrasting lifestyles in four prominent cities—Bombay, Delhi, Calcutta and Madras. Interestingly, the censorship was against scenes depicting snippets of prostitution and the case was brought to the apex court. This underlines the vagaries of morality. The prostitution scene by today’s standard was innocuous, but going by the standards of those times, it was considered a polluting influence on the public. The challenge was against the insufficient guidelines in the Cinematograph Act, 1952, which made decisions arbitrary.

The Court held that guidelines tested against the provisions of Article 19(1) of the Constitution were strong and sufficient. However, the bench held that the fine demarcation between artistic and non-artistic expression in assessing obscenity needs better understanding and clarity. The bench held this cannot be a proper and sufficient reason to annul the provisions of the Act. The bench rejected the petition that challenged the power of censorship.

The bench very strongly and presciently commented in its verdict: “Freedom of expression cannot, and should not, be interpreted as a licence for cinema magnates to make money by pandering to, and thereby propagating, shoddy and vulgar taste.” This observation has relevance even today when box office collections drive the script and treatment of screenplays.

Today, when films are clubbed with other art forms while arguing for artistic license, it is well noting the words of caution which the Justice Hidayatullah bench had added for film-makers: “It is also for this reason that motion pictures must be regarded differently from other forms of speech and expression. A person reading a book or other writing or hearing a speech or viewing a painting or sculpture is not so deeply stirred as by seeing a motion picture. Therefore, the treatment of the latter on a different footing is also a valid classification”.

If gore, violence and misogyny are bandied as cinematic eye candy, the immorality of message shouldn’t be lost either. Films not only mirror social mores, they also create them. Many schools of jurisprudence demand that laws should regulate norms which have a tendency to create schism in society. “The freedom is subject to reasonable restrictions which may be thought necessary in the interest of the general public and one such is the interest of public decency and morality, ” the Justice Hidayatullah bench had said.

However, there is a flip side to the issue as well. In Bobby Art International & Ors vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors (1996) case, an appeal was made against the judgment of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film Bandit Queen and to restrain its exhibition in India. The Supreme Court had set aside the decision of the Delhi High Court and said a film cannot be prohibited merely because it depicts obscene and graphic events. The Court held that the scenes featuring nudity and expletives served the purpose of telling the important story and that the producers’ right to freedom of expression could not be restricted simply because of the content of the scenes.

The bench of Justice SP Bharucha and Justice BN Kirpal had said: “Act clauses requires that human sensibilities are not offended by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity, that scenes degrading or denigrating woman are not presented and scenes of sexual violence against women are avoided, but if such scenes are germane to the theme, they be reduced to a minimum and not particularised”.

The verdict was a landmark of recent times regarding film censorship which gave censor-strung filmmakers reprieve and leeway to make films closer to reality. Post-Bandit Queen, a whole lot of films hit the marquee with inhibited violence and expletives. However, not many had the same social conscience and concern as Shekhar Kapur’s raw film.

In Raj Kapoor & Ors. vs. State & Ors., 1980, the Supreme Court was dealing with pro bono publico prosecution against the producer, actors and others connected with a film called Satyam Shivam Sundaram on the ground of “prurience, moral depravity and shocking erosion of public decency”. In his verdict, Justice Krishna Iyer famously said: “Social scientists and spiritual scientists will broadly agree that man lives not alone by mystic squints, ascetic chants and austere abnegation, but by luscious love of beauty, sensuous joy of companionship and moderate nondenial of normal demands of the flesh. Extremes and excesses boomerang although some crazy artists and film directors do practise Oscar Wilde’s observation: ‘Moderation is a fatal thing. Nothing succeeds like excess’”.

This practice of excess is what is being practised to the hilt now and film Animal is just a point in the case where limits of moderation have been crossed. Such unbridled cinematic treatment puts the onus on CBFC to take corrective action via censor cuts.

The dilemma of censor board had been understood by former Chief Justice SP Bharucha (Bobby Art International case ) who had proposed a test: “In sum, we should recognise the message of a serious film and apply this test to the individual scenes thereof: do they advance the message ? If they do, they should be left alone, with only the caution of an ‘A’ certificate. Adult Indian citizens as a whole may be relied upon to comprehend intelligently the message and react to it, not to the possible titillation of some particular scene.”

All said, it must be acknowledged that cinema as an art form has constantly been evolving in terms of histrionics, themes and techniques. It also mirrors social change. The presence of a censor board should, at best, act as a reminder to filmmakers of the ever-changing laxman rekha of society and impose self restraint instead of being “barked and bitten” by authorities.