By Sujit Bhar

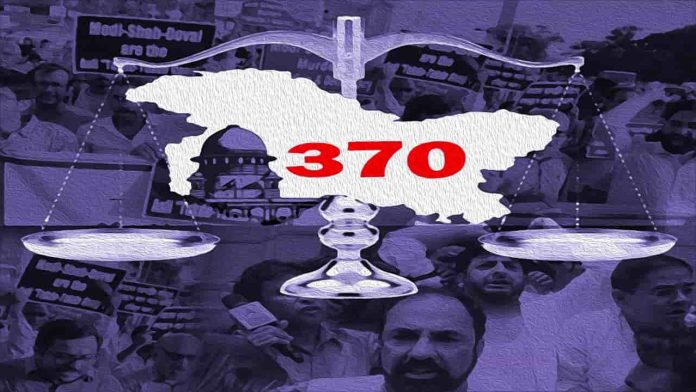

A five-judge Supreme Court Constitution bench led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud is conducting regular hearings of several petitions that have challenged the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir by the government on August 5, 2019. The Court intends to discover the constitutional nuances of the process and decide if what was done was right or wrong or if, as it seems, there exists a middle path.

This step is important, legally. It allows the judiciary to use the Constitution of India to find a “solution” to this vexing issue. The abrogation is either wrong or right, depending on which side you see it from. It has also been indicated that it was part of a natural process. The government has maintained that the process was necessary. Its version is that this “implemented constitutional transformation” was done to pave the way for better administration, good governance and economic development of the region.

Article 370, included in the Constitution in 1949, had given the state certain rights, as a condition for accession to the new Republic of India. It allowed the new state a great deal of autonomy. It allowed it to have its own Constitution, even a separate flag as well freedom to make its own laws. What were kept out of its purview were foreign affairs, defence and communications, which New Delhi retained.

What that meant in simple terms was that Jammu and Kashmir could make its own rules on permanent residency, ownership of property and even fundamental rights. It could also bar Indians from outside the state from purchasing property or settling there. Right there, might be the rights and wrongs, as per social norms. Not all of 370 was bad, not all of it was against development—figures regarding per capita income and health and even education have indicated that over the years J&K earned above average marks on many parameters.

The humanitarian angle

What the Court wants to see is if there is a humanitarian angle to this entire issue, something that impinges on the rights of the people. While the CJI, during hearings, has insisted that there was no question of complete autonomy and that J&K was indeed an integral part of sovereign India, he also wanted to find out why elections are not being held.

Fourteen hearings have been held by the time of going to press and the government has deflected a lot of queries from the bench. When the Court asked directly if the government had any timeline in mind for the “restoration of democracy” in Jammu and Kashmir (read elections), Solicitor General (SG) Tushar Mehta simply informed that elections would be “held soon”. He added that the process of updating the voters’ list was near complete and it was for the state and central election commissions to undertake the poll process. At the same time, he has declined to give a specific time frame.

The SG said that the centre was ready to conduct elections to the three-tier system—the panchayat, municipality and the legislature—in view of the improved law and order, besides overall development of the region following the abrogation of Article 370.

That solved nothing, and the government’s insistence on the “national security” angle still dangled in public view.

The CJI made it clear: “We are conscious of the fact that these are matters of national security. We understand that ultimately, preservation of the nation itself is the overriding concern. But without putting you in a bind, you and the Attorney General may seek instructions at the highest level. Is there a time frame in view?” The SG said he will “take instructions” and come back to the Court.

Status quo or court approval?

The original expectation was that these hearings will definitely determine the fate of the state’s special status. There was talk of cancellation of the controversial presidential order. However, it becomes evident that the government would no more allow the limiting of legislative powers of India’s parliament in this state.

While hearings continue, it seems that the government will give those many inches that will, actually, get it some tacit approval of the abrogation of 370 from the Court. While the Court is intent on not providing that, the arguments are beating around procedure and the finer nuances of law.

The way the government went about abrogating Article 370 was first having the state’s constituent assembly dissolved and President’s rule imposed. Thereafter, notifications were issued and the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Bill, 2019, was passed that effectively bifurcated the state into two Union Territories. The abrogation of Article 370 was executed through the Constitution (Application to Jammu & Kashmir) Order, 2019, and the subsequent Presidential notification on August 5, 2019.

The argument, therefore, was that it was simply an executive order and not a constitutional procedure that abrogated Article 370.

Parliament involved too

How the government prepared for this was evident on day 14 of the arguments, when Senior Advocate Rakesh Dwivedi said in Court that the abrogation was not an executive decision and that the entirety of the Parliament which included Members of Parliament (MPs) of Jammu and Kashmir had been taken into confidence.

For a party with brute majority this, of course, was chicken feed. The clause that any reorganisation has to be first referred to the state assembly was also avoided when the assembly was dissolved and after the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Bill 2019 was passed.

Dwivedi told the bench that, unlike the Constituent Assembly of India, the J&K Constituent Assembly enjoyed limited powers and always abided by the dictats of the Indian Constitution. This is a comment that the top court may look deeper into. As Dwivedi elaborated: “This methodology of the J&K Constituent Assembly is very akin to the juristic concept of devolution of powers. It is not an independent power like the Constituent Assembly of India.”

A steep climb

The challenges to the abrogation face a steep incline. The Court, it may be recalled, has made it clear that it will focus solely on constitutional issues. This gives the Court strength, but also ties it down to processes and formalities.

At this point, the issues at hand seem to primarily include elections in J&K—the centre has made it clear that the UT status of Ladakh will not be changed—and considering the fact that the government has, in principle agreed to that (though no timeline has been given), it all boils down to, again, procedure.

It has to be seen, in the end, if the government is able to pull out a politically-charged “court approved” slogan out of these hearings.