By Inderjit Badhwar

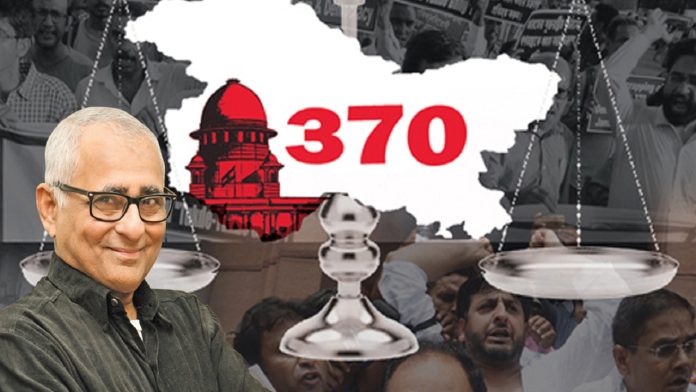

In terms of nationalist dogma, public pledges or agitations by political parties—particularly the BJP—for the abolition of the special status granted to the state of Jammu & Kashmir under Articles 370 and 35A have tremendous emotional appeal. Why, people on the street demand to know, should this Muslim-majority state which seems to want to separate from India and perhaps even join Pakistan, be mollycoddled with provisions like a prohibition on non-state people buying land in territory that is irrevocably India’s.

Actually, the BJP has itself blown hot and cold on this issue. In Modi’s first avatar as prime minister when the party was in partnership with a regional Kashmiri party—the PDP—these issues were put on a backburner. The BJP’s latest manifesto, ushering in Modi 2, has now made the abolition of these Articles a priority. The irony is that many historians argue with considerable conviction that these Articles, far from encouraging separatism, are, indeed, articles of faith which keep J&K within India’s legal and emotional embrace.

The people of Kashmir embraced India and spurned Pakistan well before India embraced Kashmir. How many people recognise this fact as the strongest building block on which to re-establish the trust and camaraderie which made Kashmir an irrevocable part of the Indian Union in 1947?

Very few. Largely because most of us are guided by emotion and political expediency. In today’s climate of instant punditry, few of us want to bother to educate ourselves to make informed judgements. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, much to the consternation of his critics, his support base and Hindu hardliners, appears to have taken an enlightened approach towards trying to calm things down in Kashmir on the basis of historical realpolitik rather than jingoistic suitability during his first term.

His first Independence Day statement was heard with great attention in Jammu and Srinagar: “The problems in Kashmir can’t be resolved through gali (abuse) or goli (bullet), but only by embracing Kashmiris.”

The formula for achieving this, his former home minister, Rajnath Singh, later elucidated, would be a “permanent solution based on five Cs—compassion, communication, co-existence, confidence-building and consistency”. He went even further. He actually debunked leaks springing from his own government that it would support a petition in the Supreme Court seeking the abrogation of Article 35A of the Constitution. This 1954 provision amended the Constitution of India to provide for special safeguards for the permanent residents of the state of Jammu & Kashmir.

“The central government has nowhere initiated anything with regard to this issue (of Article 35A). We have not gone to court. I want to say it clearly—I am not talking only about Article 35A, whatever our government does, we will not do anything against the sentiments and emotions of people here. We will respect them,” Singh said.

This could well have been another manifestation of the hard-side-soft-side approach in dealing with popular insurgencies, but it was still a move that separated dealing with genuine terror with force from seeking to accommodate legitimate differences within a solution-oriented framework. Lumping all Kashmiris into the hardline category of jehadis and pro-Pakistani Islamist separatists and crushing them ruthlessly into submitting to a historical narrative into which they cannot buy is precisely what strengthens Pakistan and its surrogates. Delhi made the mistake once of turning the war against Sikh terrorists into a war against Sikhs in general and paid a terrible price. Similarly, India’s war against armed Kashmiri terrorists often transforms itself into a war against all Kashmiris, leaving them little room to edge back into the space of mainstream politics to achieve their aims. And Pakistan gains by default.

It need not be so. Because in this case, history has been on the side of independent India. Only, India has repeatedly failed to take the historical bull by the horns. Modi’s “five Cs” were a reiteration of that often-used but least understood term “Kashmiriyat”. It does not mean a break-away from the Indian Union. It means “dignity”. This dignity, PDP co-founder and former deputy chief minister Muzaffar Hussain Baig tells me, most Kashmiris, deep within their hearts, would like to have within the Indian Union. But India, instead of accepting their embraces, pushes them away into the arms of others through denying them due process, playing toppling games and rigging the democratic process. And herein lies the irony of this vexatious problem.

Down the ages, the original people of Kashmir have been the victims of foreign masters—Afghan, Mughal, Sikh, Dogra rulers. The crowning indignity was the sale of the whole of the region for Rs 50 lakh, under the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, by the Paramount Power, Great Britain, to Maharaja Gulab Singh because of his loyalty to England. The next 100 years saw Dogra rule, autocratic and repressive, over the Kashmiri people, which they bitterly resented and finally organised the Muslim Conference (later National Conference) as a political organisation to gain azadi from monarchic absolutism and establish democracy. Their tallest leader was Sheikh Abdullah.

Mahatma Gandhi called the ceding of the Kashmir region to Maharaja Gulab Singh a “sale deed”. He made this observation in August 1947, just two weeks before India became an independent country. When much of India was burning and killing with pre-Partition communal hatred, Kashmir, still an independent country which had joined neither India nor Pakistan, was calm. Gandhi, on his first Srinagar visit, called Kashmir “a ray of hope”. The only friction in Kashmir was then between the Kashmir freedom movement and the monarchy backed by the British. The movement, called “Quit Kashmir”, was spearheaded by Abdullah’s National Conference which had rejected the Muslim League and Jinnah’s two-nation theory and was pledged to Hindu-Muslim unity. The mass agitation was directed at replacing the monarchy with a constitutional republic. And it had made common cause with India’s independence movement.

Did you know? Stone-pelting by agitators did not start with the Kashmiri youth in this century. In 1944, when Jinnah visited Kashmir to try and garner support for the Muslim League, his supporters, protected by the state police, were pelted with stones showered on them in Baramulla by National Conference agitators who had also prepared a garland of shoes to put around the neck of Jinnah. The Muslim-led secular forces of Kashmir, the most powerful mass-based group in the Valley, were stone-pelting the future leader of Muslim-majority Islamic state Pakistan!

By August 1947, India’s 561 independent states had acceded to the Indian Union. Maharaja Hari Singh had not yet made up his mind. But he was tilting towards Pakistan or independence. This was largely because the leaders of the Indian independence movement had backed Abdullah’s “Quit India” national movement directed against the Maharaja and his British backers.

Pakistan’s military attempt to annex Kashmir in October 1947 was foiled by the Indian Army after the Maharaja, who had fled his country for India, and Sheikh Abdullah, who had been released from jail and appointed Martial Law Administrator to organise the resistance against Pakistani invaders, agreed to sign the Instrument to accede to India. The Indian Union would henceforth be responsible for Kashmir’s defence, communications and foreign policy. Kashmir would retain its internal autonomy and its people would decide their ultimate fate through balloting under Indian and UN auspices after all Pakistani troops and invaders were withdrawn.

Said Abdullah, with sarcasm in his speech to the UN in February 1948: “Today Pakistan has become the champion of our liberty. I know very well that in 1946, when I raised the cry of ‘Quit Kashmir’, the leader of the Pakistan Government, who is the Governor-General now, Mr Mohammad Ali Jinnah, opposed my Government, declaring that this movement was a movement of a few renegades and that Muslims as such had nothing to do with the movement.

“Why was that so? It was because I and my organisation never believed in the formula that Muslims and Hindus form separate nations. We do not believe in the two-nation theory, nor in communal hatred or communalism itself. We believed that religion had no place in politics. Therefore, when we launched our movement of ‘Quit Kashmir’ it was not only Muslims who suffered, but our Hindu and Sikh comrades as well.”

Despite the UN resolutions, Pakistan refused to withdraw from the occupied areas. No self-determination exercise could be held and the relationship with Kashmir, through a special status provision called Article 370, was enshrined in the Indian Constitution. The provision was later accepted by Kashmir’s Constituent Assembly which converted the once princely state into a democratic republic within the Indian Union.

In his opening remarks to the Kashmir Constituent Assembly, Abdullah reiterated his state’s special relations with India: “You are no doubt aware the scope of our present constitutional ties with India, we are proud to have our bonds with India, the goodwill of whose people and Government are available to us in unstinted and abundant measure. The Constitution of India has provided for a federal Union and in the distribution of sovereign power has treated us differently from other constituent units. With the exception of the items grouped under Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communication in the Instrument of Accession, we have complete freedom to frame our Constitution in the manner we like.

“In order to live and prosper as good partners in a common endeavour for the advancement of our peoples, I would advise that, while safeguarding our autonomy to the fullest extent so as to enable us to have the liberty to build our country according to the best tradition and genius of our people, we may also by suitable constitutional arrangements with the Union establish our right to seek and compel federal co-operation and assistance in this great task as well as offer our fullest co-operation and assistance to the (Indian) Union.”

Article 35A reinforced Article 370. It was a confidence-building measure with the people of Kashmir where a plebiscite was no longer an option. As explained by the leading independent website Jammu-Kashmir.com, the idea that the residents of J&K needed to be protected was not new but had been put into effect by the Dogra Maharaja of Kashmir, who promulgated the 1927 Hereditary State Subject Order.

This distinguished between state and non-state subjects, forbidding the latter from owning land in the state. This separation of powers and a large degree of autonomy for the state was encoded in Article 370 of the Constitution of India and the subsequent Constitutional Order of 1950. The 1954 Presidential order (35A) superseded the 1950 Order and this was accepted by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad of the Jammu and Kashmir National Conference who was the prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir at that time.

On November 17, 1956, the state legislature defined a Permanent Resident (PR) of the state as a person who was a state subject on May 14, 1954, or who had been a resident of the state for 10 years, and had “lawfully acquired immovable property in the state”.

Till recently, several individuals and one NGO have challenged its legal validity. Others have called it discriminatory as thousands of residents of J&K have been denied basic rights such as owning property and sending their children to state schools because of the provisions of Article 35A.

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, has pointed out that the former maharaja of the state had stuck to this, that nobody from outside should acquire land there. And that continues. “So the present Government of Kashmir is very anxious to preserve that right because they are afraid, and I think rightly afraid, that Kashmir would be overrun by people whose sole qualification might be the possession of too much money and nothing else, who might buy up, and get the delectable places,” he said.

That, in short, was the genesis of Article 35A; it was a law meant to protect the people of the state from a huge influx of outsiders. As a result, the state’s constitution, framed in 1956, retained the erstwhile maharaja’s definition of permanent residents, that is: “All persons born or settled within the state before 1911 or after having lawfully acquired immovable property resident in the state for not less than ten years prior to that.”

Small wonder that the Modi government’s pronouncement on Article 35A during its first term drew an enthusiastic response from former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, the grandson of Sheikh Abdullah, the founder and tallest democratic leader of Kashmir. Omar tweeted: “This is a very important statement from the Union Home Minister. His assurance will go a long way towards silencing the noises against 35A.”

Why we lost Kashmir’s embrace after such an auspicious beginning sealed with blood and struggle is another story. Searching once again for that embrace and completely de-legitimising the Pakistani claim is one of the greatest leadership challenges of modern India.

And it will not be achieved through simplistic and emotionally-driven measures such as the abolition of Articles 370 and 35A.