By Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal

Modern man is anxious by nature, in fact, has always been so. What will unfold in the morrow and is anxious about simple things like exams, hunting for jobs, finding the right life-partner…. Parents of daughters of marriageable age want to know when they will find Mr Right. Therefore, it is no surprise that our society teems with palmists, astrologers, fortune tellers, but charlatans, most of all. This is when reason takes the back seat. It’s difficult to say if answers can be found by visiting holy men or holy places. But many people make a living, feeding on other people’s worries and anxieties.

Greeks consulted their oracles and soothsayers. Zoroastrians spoke to the Magi. And in our own country, great reliance was placed on the priestly classes to guide the destinies of ruling families and their empires. Only a century ago, the Russian Czar and Czarina were under the spell of Rasputin, a Russian monk with an evil streak, and a people’s movement for democratic rights was so badly handled that it gave birth to a revolution and a bloody one at that. It ended in the massacre of the Romanovs, but before that, Rasputin also found a watery grave.

The point which emerges is this—should the present generation and generations to come continue to rely on people with little or no knowledge about modern science, population trends and looming disasters? People who continue to ignore what reason warns us about the future? And as Aubrey Menen put it in “Rama Retold” (1954), truth is only found in God, human folly and laughter. Leaving God aside, are we to continue to laugh at human folly until it’s too late?

Simply put, climate change and global warming are upon us with a vengeance. Extreme climatic events like floods, droughts, storms, high temperature and freezing cold weather are going to keep getting worse and worse. This will lead to crop failures, displacement of populations, water wars, rising prices, declining national economies and unemployment on a scale unknown.

Add to the above, there is threat of wars, conventional or nuclear. Disarmament and pacifism are not on the agenda of world leaders. There is also the danger of countries using biological weapons. Many possess them and are capable of causing huge devastation to enemy populations. This is not to forget the chances of accidental leaks of poisonous substances from laboratories. The Covid-19 pandemic was a mild one compared to pandemics which may yet be unleashed by design or accident. And above all, there is the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) at a furious pace. AI is useful for the betterment of mankind, but there are dangers that things can go wrong with badly programmed robots.

Psychologists, philosophers, scientists and sociologists the world over have been very concerned about the above trends. Research is on-going to find out what exactly is going on and then work out solutions to problems created by the present generation, which may cause immense suffering to future generations. Will our grandchildren and their grandchildren ever forgive our generation which has lived happy, comfortable lives, unconcerned about the ecological damage collectively wrought to the planet?

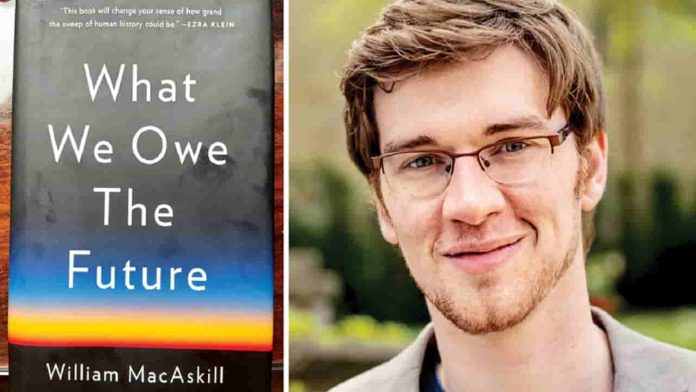

William MacAskill is a young philosopher at Oxford who has devoted a lot of time and energy to examine what the Earth and its people will look like after two hundred, a thousand or two thousand years from now. In other words, what is in store for us in the long term. This school of philosophy is “longtermism” and scholars are diving deep into the moral choices we must make today to ensure that future populations are also as happy and comfortable as we have been. Research has shown that even people who suffer from poverty, hunger and disease are happy. This may not be the case after a few centuries if a wrong direction is set for future development now. This may lead to real unhappiness and suffering.

William MacAskill has written on longtermism because to positively influence the long term future is the key moral priority of our times. He supports effective altruism and advocates using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.

His latest book is “What We Owe The Future”. His basic premise is that at the present moment, we are at a point when governments and decision makers must take some important decisions and lay down tough policies based on ethics and morality which shall help the world and future generations to survive and thrive. Otherwise, our civilisation is doomed to stagnate, decline and die. But before the death of the world, populations shall perish in millions, while the survivors shall continue to live in utter misery and penury. The scenario is bleak, but understanding the problems now can help us leave behind a thriving civilisation. It’s a serious work of moral philosophy, not science fiction. What are the morally correct things to do today to give future generations a fair chance to enjoy a safe and happy future?

MacAskill very deftly handles the subject in his book. He analyses past historical trends like the end of slavery in America which is now considered an abhorrent practice on moral grounds, but was in the 19th century an economic necessity to help plantations and was a part of rural economy. Perhaps one can compare its immorality to the immorality of the caste system in India. It’s possible that in a few generations, this social fragmentation shall see its end and Dr BR Ambedkar’s dream of a casteless society may materialise. It shall be a victory of reason over tradition, though MacSkill is silent about casteism in his book.

One of the most worrying aspects of AI which MacAskill sees, after deep study and analysis, is the likelihood of it taking over all aspects of our daily lives by the end of this century. The present is the time to be very careful to prevent AI from acquiring bad social and moral values. There is every reason for a value lock-in to happen. A lock-in of good values in AI is good because lock-ins are permanent and cannot be undone. Bad values in AI getting locked in shall be devastating. This is the real reason for being watchful of developments in AI.

Animal welfare is another area which worries MacAskill because the extent of physical torture which animals face before their meat reaches the table is morally reprehensible. Every day, millions of chicken, pigs, lamb, cattle and fish are slaughtered for human consumption. These poor animals go through extreme anxiety and suffering to keep humans well fed. He makes out a case for universal vegetarianism as a foremost moral priority. Moreover, fodder and feed for farm animals take up too much farmland, which otherwise would have been under traditional crops. The harmful effect on climate of growing fodder to fatten cows is beginning to be noticed.

An interesting example is given of the Iroquois Confederacy of native Americans. Their centuries-old oral constitution exhorts its chiefs to always keep in view, not only the present, but also future generations. They follow the seventh generation principle, and make every decision relating to the welfare and well being of the seventh generation.

In the Indian context, this means that if the Constitution passed by our leaders in 1950 was the work of our grandfathers, then their seventh generation would probably be born around 2100 and be in leadership positions when the 200th anniversary of the Constitution is celebrated. Do our policies today have the welfare of the 2100 generation in focus? Do we keep social welfare and justice and human rights always in focus, and eschew caste and communal politics? Class, caste, status and religions barriers must be broken down before our future overtakes us. It’s a “now or never” type of situation.

“What We Owe The Future” is a serious philosophical work in simple language which even a lay reader can understand. For the serious researcher, there are detailed references to important studies. The book is divided into five parts, each with two or three chapters, but what is of interest are small articles within each chapter on topics like AI takeover, great power war, fossil fuel depletion and technological progress slowing down.

It is this weaving of different studies into a compact whole which makes the book a valuable addition to one’s library. And for this reason, it will be read by future generations as something some people from our generation tried to achieve for a better future for the world.

—The writer is former judge, Punjab & Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York