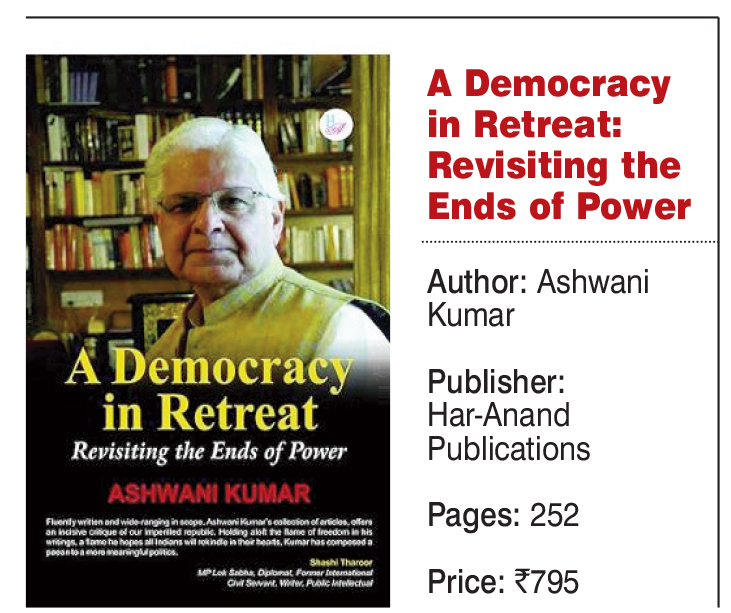

Eminent lawyer and former parliamentarian Dr Ashwani Kumar’s book, calling for democratic renaissance in an India that is resounding with partisan voices, should be read by all for its fine balance and searching style

By Prof Upendra Baxi

Dr Ashwani Kumar, with his poignant accent on dignity, has secured for all (what Indian Express editor Raj Kamal Jha writes in a fond blurb) a “space for conversation” for democratic renaissance (to borrow a memorable notion made vibrant by former Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra). He brings to mind, economic historian Joseph Schumpeter’s distinction between “government by election” and “government by discussion”. Both are essential to a well-functioning democratic order but that very space is endangered by shrill, partisan voices on all sides, leaving very little scope for debate, far from the epochal eras of classical Indian debates (called shastartha).

Not contention or assertion for its own sake, nor prejudice or partisanship, but reasoned (and dispassionate) exploration of key themes, issues and discourse furnish passports to achieve “dignity” in discourse of governance, development, rights, and justice agenda of the Indian Constitution; this, Ashwani Kumar insists, provides almost the sole justification for democratic discourse and ordering.

This critical anthology most giftedly brings to us the wisdom of his being. Dr Ashwani Kumar thus brings in the distillation of a life-long experience of wise lawyering, an insider perspective of disciplined loyalty of a national party for four decades, a ringside experience of national and global governance, a love for poesy that beings joy, and a richly sustained reasoned discourse. In this last cadence, he brings to life so much of Percy B Shelly’s wisdom when he wrote that “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world”.

There are many abiding messages in this wise collection. I instance a few, giving a flavour of these essays. “The nation needs an accommodative democratic politics based on conciliation and consensus, anchored in a constructive contest of ideas as a part of an ongoing national…conversation.” Note that the learned author does not begrudge “democratic triumphalism” for winners at the hustings (who can?), but constantly urges “bipartisan commitment” on the “non-severability of justice, freedom, and dignity in the service of democracy” (pages 83-84 ). Is this not relevant also to democratic governance all over the globe, just as it is indispensable for India?

Stressing limits of competitive politics and populisms is not to gainsay the capture and maximisation of political powers and processes of governance and development, but to commend the constitutional framework within which competitive politics must be waged. Power, to somewhat extend the wise words of the learned author, is not an “invitation” to “transgress” the protocols of a decent and just society. Dr Ashwani Kumar’s notion of dignity comes closest to that of Professor Avishai Margalit who builds a “foundation” for a decent society, or a civilised society, as one whose “institutions do not humiliate the people under their authority, and whose citizens do not humiliate one another. What political philosophy needs urgently is a way that will permit us to live together without humiliation and with dignity”.11 Dr Ambedkar sought to achieve precisely a decent constitutionally desired social order, particularly through the abolition of all forms of “untouchability” through Article 17, as a right to equality and dignity of all human beings.

The “fraying of Indian democracy” (page 101) is certainly due to ships passing by the night—a state of non-conversation with the suffering other and the lack of an abiding concern for a just amelioration of human and social suffering. No “fatal cocktail of power” but only the languages of “constitutional principles” (page 101) may secure and serve the logics, and paralogics, of accountability This may primarily be attained by “ennobling leadership” (ibid). But is the best way to follow the spirit of Confucius, articulated by the “wisdom of Meniscus”, that a “great fortune of a people would be to keep ignorant persons from public power and secure their wise men to rule them”? (page 102, emphasis removed). However, the ideal of the “wise men” (and I necessarily add “women” and other genders) to realise the constitutional framework in response to a Covid pandemic is superbly narrated in Chapter 17 and 18, and at many other sites in this critical anthology.

One hopes that in the near future the learned author will revisit the perils posed to democratic ordering and functioning by epistocracy and meritocracy. He already does this in the superb chapter 26 of the book where he discusses, in some detail, “constitutional rights, judicial review, and fundamental rights” (incidentally the only chapter with proper footnotes, whose absence elsewhere teasingly invites research participation by the readers)!

Dr Ashwani Kumar refreshingly highlights Justice Anthony Barak’s insight that the “judgement of a voter is not a substitute for the judgment of a court”. I must also add that I have always maintained a distinction between social action litigation (SAL) and public interest litigation (PIL) because I believe that while labels can be borrowed (like PIL), histories cannot be! In any event, the bulleted checklist of many questions listed in pages 163-166 is indeed quite helpful. And I quite fancy, instead of the category of judicial restaintivism, Blaise Pascal’s expression “self-research and self-reproach” (page 167). This is because I have always believed that the highest power is at the same time a source for vulnerability, even as presenting in Justice PK Goswami’s memorable words the hope that the “Supreme Court of India is the last resort for the bewildered and the oppressed”.2

I endorse fully the view that in a democratic society the emphasis on the “recognition of the boundaries of power” and the “fulsome acceptance of judicial fallibility” (page 160) are the bulwarks of constitutional judicial review processes and power. How I wish that the learned author had also recognised some leading Indian academic writing saying much the same on this, and allied subjects, if only in a spirit of camaraderie combating academic colonialism!

Of course, when all is said, “invented” injuries and “imagined scandals” almost “coalesce in perpetuating falsehood”, rendering “justice an optical illusion” (page 121). But is one certain that such a situation is brought about only when “wise” people are not in positions of power?

One must accept the conclusion of the learned author that we all are collectively responsible for the “diminished Indian democracy” (page 126), but that should not prevent us from saying also that great institutions of constitutional governance—both Parliament and the Supreme Court—have been, across 75 years of the registers of the Republic, incapable of preventing “democratic erosion” occurring through the “tyranny” of majority” (Chapter 20). There is clearly an “institutional deficit” in “advancement of constitutional goals”. All the same, he writes, we need not succumb to despair “because we know that our dignity, like our destiny, lies within ourselves” and we may not be deterred” from pursuing “the dignitarian agenda as a purpose in perpetuity” (page 132).

One may only say “Amen” to this last quoted observation, while expressing a wish that many senior lawyers and retired Justices, in their writings, will share the wise balance and the searching style of Dr Ashwani Kumar.

—The author is an internationally-renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer

————-