By Justice Kamaljit Singh Garewal

Charles-Edouard Jeanneret (1887-1965), also known as Monsieur Le Corbusier, was a Swiss-French architect, painter, designer and urban planner. He was born in Switzerland and moved to Paris for work in 1921 where he set up his design studio and practice and became a French citizen in 1930.

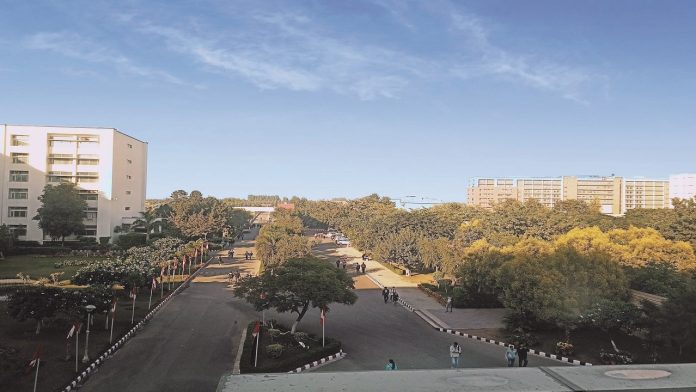

In 1950, after long years in design and modern art, Corbusier took up planning the capital of Punjab. Corbusier came from Paris where sunny days were few compared to India. Here he had sun, space and verdure on his mind when he began work on designing the city. Sun was free and plentiful. Space needed careful planning for all the needs of the government and residents. And verdure required extensive planting of avenue trees and laying of parks. From these elements, Corbusier created for a world-class garden city. The city must be saved before it is destroyed by bureaucratic shortsightedness, deviations and defiance.

A recent judgment of the Supreme Court in Residents Welfare Association vs Union Territory of Chandigarh has come at the right time. It shall stand as a landmark of urban development jurisprudence. The opinion is in three parts. After recounting the planning and architectural rules governing Chandigarh, the Court came to the conclusion that it was necessary to preserve the heritage of the city. Fragmentation of a housing site in Phase I of Chandigarh was not permissible under the Chandigarh Master Plan, but construction of three floors was allowed. But the Court failed to realise that while permitting construction of three storeys, the apartment should be allowed to be validly transferred if it has covered all other norms. Such a transaction did not amount to fragmentation. Secondly, the Court converted the Heritage Committee into a powerful body to clear all construction activities in Chandigarh. And lastly, the Court recommended making environmental assessment mandatory for urban development and appealed to the Legislature, the Executive and policy makers at the centre as well as at the state levels to make necessary provisions for carrying out Environmental Impact Assessment studies before permitting urban development. With such a sweeping direction, the judgment seems to acknowledge that environment has a crucial effect on our cities.

The Frenchman’s involvement in the boondocks of Punjab’s foothills to build a city is itself a fascinating tale. When the planning began, after Partition, it was thought that the capital city of East Punjab shall be a fitting replacement for the old city by the river Ravi, named after Lord Rama’s son Lava. Lahore had always been the capital of the Punjab, whose provincial boundaries in 1947 had stretched from the left bank of the Indus to the right bank of the Jamuna and even included Delhi, the capital of India. After Lahore was awarded to West Punjab, the government of East Punjab became homeless. It moved temporarily to its old summer capital in the mountains, and resolved to build a modern, brand new, spanking city in the foothills where the mountains meet the plains.

The site for the Capital Project was a sparsely populated, rocky, windswept plateau where nothing grew, but the place had a stunning mountainous backdrop of the lower Shivaliks. Beyond the foothills was the Kasauli range and still further, the snow-capped Dhauladhar and Churdhar added their majesty to the landscape.

The capital city was named after “Chandi (the Fierce)”, the demon-destroying form of the Hindu goddess Shakti or Durga, whose ancient temple was nearby. In India, mythology is always close at hand. The site was bang in the centre of Punjab and proved to be excellent in most respects, but not all. It lacked water, rail and road connectivity, but these problems were not insurmountable. No one imagined that 70 years later Chandigarh would not remain a pretty little island in Monsieur Le Corbusier’s sophisticated urban plan. The City was destined to grow and even earn the inelegant epithet—Tricity. When Chandigarh came up, it was part of one state.

In 2023, Chandigarh is surrounded by three states—Punjab, Haryana and Himachal, all of whom had been a part of the Punjab. Chandigarh is a modern, stylish, and sophisticated lady being wooed by at least two, if not three, suitors. It is zealously guarded by its parent sitting in the nation’s capital, New Delhi.

Other cities of India are much bigger and many centuries old. They speak to us of the days gone by, of their glory through their buildings, architecture, forts, palaces and temples. For those who care, there is much of heritage value to explore and experience, to get a feel of the gaiety and splendour of the Sultanate and the Raj, of the days gone by. These cities have real heritage which lie well preserved.

Chandigarh is modern and at 70, still growing culturally. This was to be expected because the City was designed by a famous French architect and urban planner, a pioneer of modern architecture. Corbusier (Corbu or crow) was to architecture what Picasso was to modern art. Corbusier expected people to give full expression to their thoughts through music, theatre, art, sculpture and photography, and the people of Chandigarh have done this in good measure. Unfortunately, nothing of rural Chandigarh has been preserved. Not even a Persian wheel, an artesian well, a mud hut, household items, old village furniture, handicrafts….Nothing remains of heritage value; it all got destroyed by the Corbusian vision. Owners of land received a few hundred rupees per acre as compensation and left without demur. Nowadays the price of land is mind boggling.

There are many other large cities which have grown to humungous size in the past 30 years. Delhi is 1,480 sqkm on the banks of the Jamuna and within it is New Delhi, a mere 42 sqkm, the latest of its seven cities. Unfortunately, New Delhi has got surrounded by Gurgaon, Faridabad and Ghaziabad. The other great cities are on the Oceanside—Mumbai is 600 sqkm, its island only 68 sqkm; Chennai is 426 sqkm; Kolkata is 206 sqkm on the Hooghly. Bengaluru or Bangalore was at one time a hill station and cantonment. Pune or Poona was the centre of the Marathas and later developed into a military base and centre of education. Hyderabad, Lucknow and Jaipur were princely cities, while Varanasi was one of the oldest cities of the world, a place of religion and pilgrimage. All of them are heritage-rich, but running these cities must be challenging.

Within Chandigarh itself, the original concept was of a planned, orderly, modern city of 29 sectors, each about a square kilometre, making the original city just 30 sqkm. Western superstition forbade sector 13; therefore, the sectors were numbered 1 to 12 and 14 to 30. Here an interesting twist occurred. The sum of any two sectors opposite to each other would be 13 or divisible by 13. For example, opposite sector 2 is sector 11 and then come sectors 15 and 24. Simple addition gives us: 2 + 11 = 13, 11 + 15 = 26, 15 + 24 = 39. The number 13 doesn’t really leave us. Was Corbusier’s Chandigarh jinxed from the start? Perhaps he was not aware that the number 13 is a lucky number in our mythology. The jinx, if any, was broken by the Swastika sculpted on a wall of the Martyrs’ Memorial, near the plaza between the High Court and the Secretariat. Corbusier defeated superstition. The Capitol Complex was named in the list UNESCO World Heritage sites in 2016.

In a few decades, the original phase I got overwhelmed by the need to accommodate an ever increasing population and its concomitant, multifarious demands. The city was extended to phase II in 1974, within the capital project spread over 114 sqkm. But that is not all. The city was actually suffocated by Mohali, Panchkula and the Western Command. Punjab, not being content with Mohali, planned New Chandigarh in 2008 and another urban development project in 2012, near the Chandigarh International Airport. Himachal, not to be left behind, has set up the Baddi-Barotiwala-Nalagarh Development Authority as an industrial and a world class pharmaceutical hub to capitalise on its proximity to Corbusier’s dream city. We are now headed skywards, with multi-storey behemoths coming up everywhere in nearby Punjab and Haryana.

It may already be too late to impose restrictions on projects which are nearing completion. The judgment of the Supreme Court shall give a direction to urban planners and put an end to urban chaos and confusion seen everywhere. This must happen before decay sets in and cities begin to decline.

—The writer is former judge, Punjab & Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York