By Binny Yadav

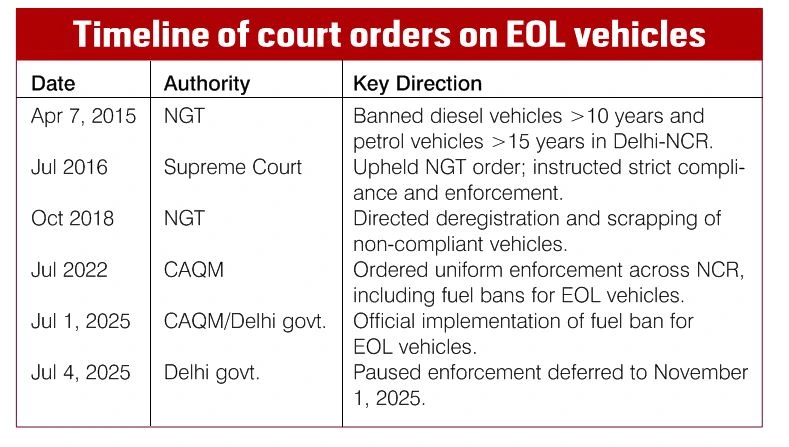

On July 1, a long-awaited ban on refuelling End-of-Life (EOL) vehicles in the capital came into effect—only to be paused within three days. In those 72 hours, the city was given a fleeting glimpse of what strict vehicular regulation might look like. But just as quickly, that window was slammed shut by the BJP-led Delhi government, citing “practical difficulties”.

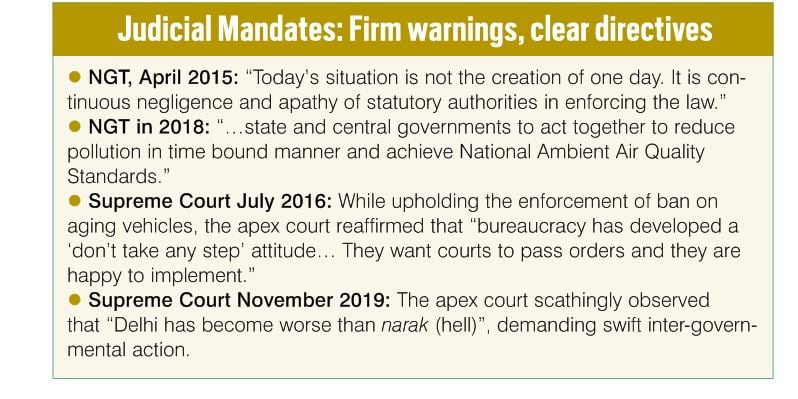

This isn’t a governance hiccup. It is part of a decades-long pattern in which successive governments—Congress, BJP, AAP, and now BJP again—have chosen to retreat from environmental mandates, no matter how severe the public health toll. While Delhi reels year after year under life-threatening air pollution, each administration has found new justifications to delay or dilute hard decisions, ignoring court orders, scientific evidence, and the suffering of its people.

TWO LEADERS, ONE REVERSAL—BUT DIFFERENT EXCUSES

The official reasoning behind this U-turn by the current government reveals that it is scrambling to defend the indefensible. Chief Minister Rekha Gupta framed the rollback as a measure to protect common citizens from undue hardship. Her statement emphasised that the policy was implemented without adequate notice or support mechanisms for those dependent on older vehicles. “Thousands of Delhiites… have not received adequate notice or alternatives. Immediate enforcement without support mechanisms would be unfair,” clarified Gupta.

Delhi’s Environment Minister Manjinder Singh Sirsa justified the pause on administrative grounds—pointing to the lack of readiness at fuel pumps, absence of a functional tracking mechanism for banned vehicles, and confusion over enforcement responsibilities. “Operational and technological systems—including ANPR (automatic number plate recognition) integration at fuel pumps—are incomplete. Without these, enforcement would be chaotic and counterproductive,” he maintained.

Arguments differ in tone—one empathetic, the other procedural—but lead to the same conclusion—the policy failed not because it was flawed in principle, but because the government lacked the planning, coordination, and political courage to implement it.

HOW MANY WINTERS MUST DELHI ENDURE?

The stakes are not abstract. EOL vehicles—those past their legal lifespan—emit pollutants at exponentially higher rates than newer models. A 15-year-old petrol car or a 10-year-old diesel vehicle can emit up to five times more particulate matter than a BS-VI compliant counterpart. When these vehicles continue to ply on Delhi’s roads, they transform the city’s air into a slow-moving public health disaster.

Despite this, governments have consistently resorted to stop-gap measures: odd-even schemes, smog towers, dust suppression trials, and construction bans, all while avoiding the structural reforms that judicial bodies have repeatedly demanded. The latest reversal is simply another entry in this long record of evasion.

A FAILURE OF BOTH POLITICAL COURAGE AND INSTITUTIONAL MUSCLE

While the Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM)—a statutory authority created precisely to enforce such measures—has directed compliance, it lacks the legal teeth to hold governments accountable for non-compliance. Delhi’s environment department, the transport ministry, fuel station operators, and law enforcement are often out of sync, making even basic enforcement unworkable.

And it’s not just Delhi. Other NCR (National Capital Region) states have followed suit in pushing implementation dates further into the future. CAQM’s revised timeline now sets Delhi’s deadline at November 1, 2025, and April 1, 2026, for surrounding regions. This slow-rolling of enforcement sends a dangerous message: environmental court orders are negotiable.

THE UNSEEN COST: LIVES AND LUNGS

Scientific studies have consistently shown that vehicular emissions contribute 20 to 30 percent of Delhi’s PM2.5 pollution. Exposure to such pollution increases the risk of asthma, stroke, lung cancer, and premature death. Children growing up in Delhi are said to have “weaker lungs” than those in other Indian cities, and the elderly face constant health threats.

Yet the political establishment continues to treat this as a navigable nuisance, not a public health emergency. The Supreme Court and NGT (National Green Tribunal) orders were meant to be non-negotiable safeguards for public health, not optional policies at the mercy of electoral cycles.

DELHI’S TOXIC AIR IS NO ACCIDENT

This policy reversal is not a case of premature roll out—it is a reflection of long-standing institutional dysfunction. The Delhi government had three years since the CAQM’s initial directive to prepare enforcement mechanisms, coordinate across departments, and raise public awareness. That time was squandered.

Meanwhile, Delhi’s citizens, especially its poorest and most vulnerable, continue to breathe toxic air because every government—past and present—chooses expediency over environment, politics over people, and postponement over accountability.

Unless there is political courage to match judicial clarity, Delhi will remain trapped in this endless cycle of pollution, postponement, and policy paralysis. And its residents will continue paying the price—with their lungs, their health, and their future.

—The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist, lawyer and trained mediator