By Binny Yadav

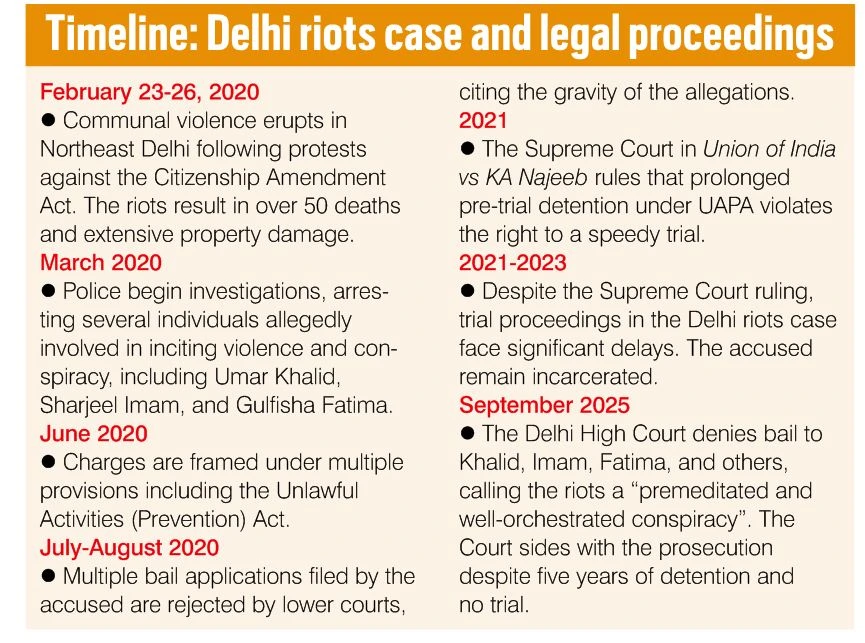

“Justice delayed is justice denied.” This timeless maxim rings painfully true in the ongoing saga surrounding Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, Gulfisha Fatima, and others, accused in the February 2020 Delhi riots case. More than five years have elapsed since their arrests, yet the trial remains a distant prospect. The Delhi High Court’s recent decision to deny bail to these individuals, many of whom have spent over half a decade behind bars, is not just a ruling on bail—it is a chilling testament to the erosion of due process, presumption of innocence, and the very essence of liberty in contemporary India.

This case encapsulates a disturbing trend: the normalisation of prolonged pre-trial incarceration under the draconian provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The ruling does more than just uphold the prosecution’s narrative of a “premeditated and well-orchestrated conspiracy”—it sends a disquieting message about the diminished role of the judiciary as a guardian of constitutional freedoms in the face of executive overreach.

THE UAPA: AN OVERBROAD WEAPON

To understand the gravity of this judgment, one must first comprehend the nature of the UAPA itself. Enacted with the legitimate aim of combating terrorism and preserving national security, the UAPA is marked by its broad, vague, and often subjective definitions of “terrorism” and “unlawful activity”. The law’s expansive reach empowers the state to file charges on flimsy and circumstantial evidence, often targeting individuals for their associations, speeches, or ideologies rather than any concrete violent acts.

The accused in this case face serious allegations—claims of conspiracy and incitement to violence during the 2020 Delhi riots, a tragedy that left many dead and property destroyed. Yet the evidence presented—based on WhatsApp chats, social media posts, and political speeches—raises critical questions about what the law deems sufficient to brand someone a “terrorist” or conspirator. This ambiguity, far from being a mere technicality, strikes at the heart of civil liberties and the democratic right to dissent.

THE BAIL DILEMMA UNDER UAPA: A LEGAL LABYRINTH

Bail jurisprudence under the UAPA is a notoriously difficult terrain for the accused. Unlike regular criminal laws, where bail is the rule and custody the exception, the UAPA reverses this presumption. Section 43D(5) of the Act effectively bars bail unless the court is convinced that the accusation is “not prima facie true” or the accused is unlikely to commit a terrorist act if released. This flips the constitutional safeguard of “innocent until proven guilty,” turning bail hearings into trials by inference.

In the Delhi High Court’s ruling, this principle is painfully evident. Despite the trial yet to begin and the accused languishing in jail for years, the Court gives the prosecution the benefit of every doubt, dismissing the liberty interests of the accused with scant attention to the evidence’s quality or the systemic delay in trial proceedings.

SPEEDY TRIAL: THE FORGOTTEN RIGHT

The most glaring injustice in this saga is the slow march of justice itself. Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, which the Supreme Court has repeatedly interpreted to include the right to a speedy trial. In the 2021 decision of Union of India vs KA Najeeb, the apex court underscored that prolonged pre-trial detention under special laws like the UAPA, without progress in trial, violates fundamental rights.

Yet, this precedent seems ignored in the Delhi High Court’s ruling. The accused remain in jail, not because of any proven guilt, but because the wheels of justice turn at a glacial pace—an indictment of systemic failures ranging from overburdened courts to deliberate procedural delays. The result is what many legal experts term “pre-trial punishment”: incarceration before conviction, a punishment in itself that violates principles of justice. The judicial acquiescence to this reality effectively grants the state a tool to silence dissent through indefinite detention.

JUDICIAL DEFERENCE AND ITS DANGEROUS CONSEQUENCES

The judiciary’s role in such cases cannot be overstated. Courts serve as the final bulwark against the misuse of laws and the arbitrary exercise of state power. However, there is an emerging pattern where courts—perhaps influenced by national security imperatives—grant the prosecution wide latitude, often at the cost of the accused’s rights.

In this case, the Court’s uncritical acceptance of the state’s conspiracy narrative, without rigorous scrutiny of the evidence, signals a troubling shift towards judicial deference over judicial oversight. This approach undermines the separation of powers, eroding trust in the justice system and weakening democratic checks on executive excesses.

THE BROADER SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT: CRIMINALISING DISSENT

Beyond the courtroom, the case sits at the volatile intersection of politics, identity, and dissent in India today. Many of the accused are prominent activists and intellectuals known for their outspoken criticism of government policies and social injustices. The use of the UAPA and other anti-terror laws in this context raises the spectre of selective prosecution aimed at stifling dissenting voices.

The Delhi riots themselves remain politically charged, with narratives contested fiercely in the public domain. In such a climate, the justice system’s impartiality is critical. Yet, when due process is sacrificed, and prolonged incarceration becomes a norm, the risk is not merely individual injustice, but the gradual shrinking of democratic space itself.

RECLAIMING THE CONSTITUTIONAL PROMISE

The Delhi High Court’s refusal to grant bail to Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam, and others is emblematic of a legal and moral crisis—a crisis that challenges the foundations of justice in India. It compels us to ask difficult questions: How can a democracy reconcile national security with individual liberty? What safeguards must exist to prevent the misuse of laws meant to protect us? And critically, what role must the judiciary play to uphold constitutional guarantees amid political turbulence?

The answer lies not in harsher laws or punitive delays, but in recommitting to the rule of law, where every individual—regardless of political views—is entitled to the presumption of innocence, fair trial, and timely justice.

In this struggle, the courts must reclaim their role as protectors of liberty, ensuring that laws like the UAPA do not become instruments of repression. Until then, the ongoing incarceration of the accused serves as a stark reminder that justice, when delayed or denied, ceases to be justice at all.

The case has since been appealed in the Supreme Court with a pending hearing, and the hope that timely and just adjudication will finally deliver justice.

—The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist, lawyer and trained mediator