By Dilip Bobb

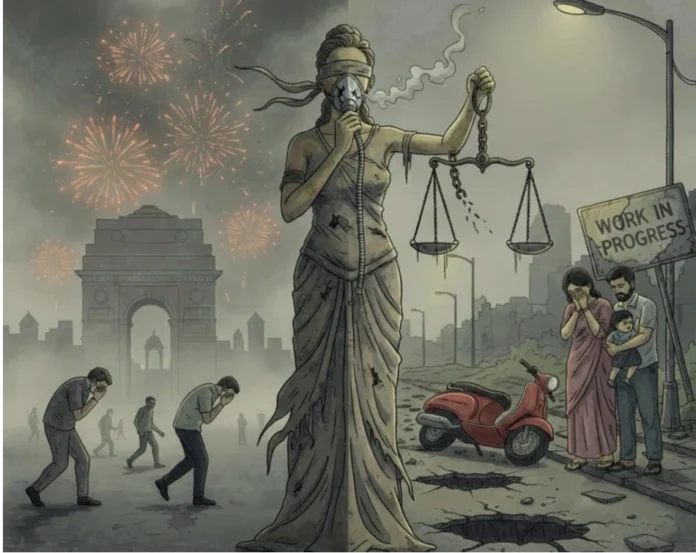

The blatant disregard of the Supreme Court order on firecrackers and timings in the National Capital Region on Diwali was just one of the many civic-related issues that have trapped citizens in a hopeless, even deadly situation. Ahead of the festive season, the Court had relaxed the total ban on the sale and use of firecrackers in the National Capital Region by allowing government-approved “green crackers” on a “test case basis”. The order, passed by a bench of Chief Justice of India BR Gavai and Justice K Vinod Chandran, attempted to strike a balance between the livelihood concerns of the firecracker industry, festive traditions and the public health crisis caused by air pollution in the region every winter.

This temporary relaxation modifies a series of previous orders by the Delhi government and the Supreme Court that had imposed a complete ban on all kinds of firecrackers in the National Capital Region in recent years. That the official timings given for use of crackers was openly violated due to lack of any police or official intervention, as was the use or misuse of “green” crackers, showed that enforcing the apex court’s orders was left hanging in the heavily polluted air. The illegalities that ensued—over 1,000 people, including children, were admitted to hospitals with respiratory problems—comes under the right to life clause of the Constitution. Yet, the civic apathy continues. As former Niti Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant stated: “The Supreme Court prioritised the right to burst crackers over the right to live and breathe.”

Last week, two prominent citizens of Bengaluru criticised the government for the number of potholes and garbage, leading to a messy confrontation with the Congress-led government. Kiran Mazumdar Shaw, founder of Biocon, and Mohandas Pai, former Infosys CFO, were concerned about the civic infrastructure collapse which was harming business, blaming the Greater Bengaluru Authority. Shaw had posted on X that a Chinese client had wondered why India’s exalted IT hub suffered from daily traffic jams, potholed streets and mounds of garbage. As in so many similar cases involving municipal negligence, politicians (Karnataka Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar) intervened, shielding civic authorities for their non-performance.

Indian courts have often held authorities accountable for deaths, injuries, and damages caused by poorly maintained roads and potholes. Instead of imposing direct fines on civic authorities, courts have ordered compensation, and in one case, ordered the suspension of toll collection on a pothole-ridden road.

Recently, in a significant ruling, the Bombay High Court mandated a liability regime for civic authorities and contractors, making them directly responsible for pothole-related deaths and injuries. It ordered compensation of Rs six lakh for fatalities and between Rs 50,000 and Rs 2.5 lakh for injuries. The Court fixed personal liability on senior officials for delays in road repairs and warned that they must bear monetary costs from their own pockets to understand the gravity of the issue. This ruling established the right to safe, pothole-free roads as part of the fundamental right to life under Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court had earlier, upheld a Kerala High Court order affirming that commuters cannot be forced to pay tolls on highways that are riddled with potholes and in poor condition. This decision reinforced that authorities cannot charge citizens for deficient services, prioritizing public welfare over the financial interests of toll operators. In 2020, the apex court dismissed a plea from the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike that challenged a High Court order. The order had directed the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike to compensate victims of accidents caused by poor roads, recognizing that citizens have a right to claim compensation for such negligence.

While there is no specific “pothole law” in India, citizens do have legal options to hold authorities accountable for damages or injuries. Citizens can sue the government or the responsible authority (such as a municipal corporation, state public works department, or National Highways Authority of India) under the law of torts for negligence.

A writ petition can be filed in a High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution, arguing that injuries or death due to potholes violate the fundamental right to life under Article 21. In some cases, consumer forums have admitted claims for damages caused by potholes, treating the matter as a “deficiency in service”.

However, for any such claim to be successful, citizens must gather evidence, including photos of the pothole, police and medical reports, and invoices for repairs. They should also file an official complaint with the relevant authority. This is so time-consuming that it actually acts as a deterrent.

Potholes account for nearly 0.8 percent of road accidents, 1.2 percent of deaths caused by road accidents, and 0.7 percent of injuries, reflecting infrastructural and institutional shortcomings. This is primarily attributable to poor quality road construction material, lack of maintenance and timely repair of roads, and negligence of municipal authorities.

Under Article 300 of the Constitution, the government can be held liable for tortious acts committed by its servants, including negligence in road maintenance. Courts have recognized this liability in several cases, especially where pothole accidents have led to serious injury or death. Given the rising number of accidents due to potholes, this challenge also undermines India’s commitment to road safety. As part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the UN Decade of Action for Road Safety 2021-2030, a target has been set for reducing road deaths by 50 percent by 2030. The State is liable in law for the acts of its officials which makes them susceptible to claim for damages on account of road negligence by municipal authorities which directly contribute to life-threatening conditions for commuters.

The Supreme Court in State of Rajasthan vs Mrs Vidyavati, observed that the State shall be held liable for its tortious acts and that the ambit of Article 300 would not be limited only to the contractual liabilities. Under Article 300 of the Constitution, the State can sue or be sued as a juristic personality. In S Rajaseekaran vs Union of India, the top court acknowledged the serious risk to public safety posed by poorly maintained roads, particularly the prevalence of fatal accidents caused by potholes.

The top court in its order dated July 20, 2018, noted that municipal authorities, entrusted with the duty of maintaining roads under applicable laws, had failed to discharge their responsibilities effectively, leading to unavoidable loss of life on account of pothole accidents. This legal recognition of the State’s accountability lays the groundwork for victims to seek redress in pothole accident cases under Article 300. The Court also referred to newspaper reports indicating that deaths caused by pothole accidents had surpassed those resulting from terrorist attacks, underscoring the gravity of the situation.

Given the alarming reality, the Court emphasized that the legal representatives of victims who had lost their lives due to such pothole accidents were entitled to claim compensation as a tortious claim, reinforcing the principle that the State and its agencies bear responsibility for ensuring safe road conditions and may be held accountable for negligence in fulfilling its duties.

The Bombay High Court in a suo motu public interest litigation had observed that right to have properly maintained roads is a part of fundamental rights guaranteed by Article 21 of the Constitution, and in the event of any loss caused due to its violation, the citizens have a right to seek compensation.

While courts have been taking cognizance of the implications of bad road conditions on human lives, this does not appear to have spurred municipal authorities into action. Poor road conditions and Indian potholes remain a permanent problem across almost all of urban India, causing record accidents each passing year. Further, the unduly long time taken by civil courts or tribunals coupled with unempathetic bureaucratic response in court proceedings, to dispose of claims, acts as a deterrent to affected families who need immediate and adequate relief due to loss of family members. This is particularly tragic in cases involving accidents caused by potholes where immediate compensation is essential if the victim is the sole earner of the affected family.

In Debayan Mitra vs The Municipal Corporation of Delhi, the Court held that general damages of Rs 10,000, special damages of Rs 1,240 and costs of the suit was to be awarded to the plaintiff by the municipal corporation. The plaintiff had fallen into a pothole filled with water while returning home and had sustained severe injuries.

Statutes such as the Fatal Accidents Act, 1855, and the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, provide for compensation to be paid to the family of a person for the loss by death by actionable wrong. Section 136-A of the Motor Vehicles Act provides for provision of electronic monitoring and enforcement of road safety which is to be ensured by respective state governments.

Some municipal corporations have rules or regulations governing the maintenance of roads and compensation to be provided to the victims. However, there no standard rules adopted for engagement of contractors for building, repair and maintenance of roads, their periodicity, the technology or materials to be used having regard to local conditions, and most importantly, the accountability of employees of the municipal authorities responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of roads in the event of any fatality or serious injury.

Earlier this month, a Supreme Court bench of Justices JB Pardiwala and KV Viswanathan, reacting to mounting road fatalities, issued a set of directions aimed at protecting pedestrians, enforcing helmet rules and curbing wrong lane driving, among other common violations and declared that safe and encroachment-free footpaths are vital for pedestrian movement. The ruling said that the National Highway Authority of India, state governments and municipal authorities are “duty-bound” to ensure that footpaths are built properly and remain encroachment-free to allow pedestrians a safe opportunity to walk and cross the streets.

Pedestrians comprise 20 per cent of total fatalities in road accidents, according to the Road Accidents Report in India by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Out of 1,72,890 deaths in road accidents in 2023, 35,221 were pedestrians.

In the United States, the Federal Tort Claims Act, 1946, provides legal means for compensating individuals who have suffered personal injury, death, or property loss or damage caused by the negligent or wrongful act or omission of any employee of the government. Under the Federal Tort Claims Act, the federal government acts as a self-insurer, and recognizes liability for the negligent or wrongful acts or omissions of its employees acting within the scope of their official duties. The Administrative Code of New York City (commonly known as the “Pothole Law”) has played a significant role in governing the accidents resulting from poorly maintained roads. This provision bars civil actions against the city for property damage, personal injury, or death caused by defective, unsafe, dangerous, or obstructed streets, highways, bridges, wharves, culverts, sidewalks, or crosswalks, including any attachments or encumbrances, unless one of the following requirements is met. New York’s approach places the onus of reporting road potholes on citizens while ensuring state action—a model India can emulate.

The right to life and one’s personal liberty is one of the most fundamental rights. Any grievous hurt to an individual or loss of life due to negligence falls within the realm of a criminal act under Indian laws. Accidents due to potholes must be seen not just as infrastructure failures, but as breaches of public trust and safety. However, the negligence of the responsible officers or employees of municipal authorities causing death or injury due to potholes, are hidden under the guard of institutional failure, without any recourse. Naturally, the lack of accountability of any specific person results in the general lack of institutional empathy towards such negligent approach.

While the Constitution permits actions against the State for tortious liability under Article 300, and judicial precedents have upheld the duty of municipal and state authorities to maintain roads, there is no legislation that explicitly governs the accountability of government bodies for such accidents. This lack of a uniform legal framework results in uncertainty and inconsistent enforcement with respect to determination of liability as well as grant of compensation.

Victims of accidents caused by potholes can pursue tort claims in civil courts, file writ petitions for violation of fundamental rights under Article 21, or seek compensation under statutes such as the Fatal Accidents Act, 1855, and the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988. These remedies provide both constitutional and statutory routes to hold authorities accountable for potholes in Indian roads. India does not currently have a standalone law addressing pothole accidents. Courts evaluate these claims based on facts, precedents, and judicial discretion, often resulting in varying outcomes. The absence of codified standards contributes to inconsistent enforcement, leaving families of victims in uncertainty and prolonged legal battles.

India needs a codified legal framework that clearly defines the road maintenance duties of public authorities and establishes a time-bound compensation process for pothole accidents. There should be standardized contractor protocols, regular audits, and accountability measures. Only stricter penalties for negligence and an efficient grievance redressal system can ensure faster relief and greater public safety.

Legal precedent clearly holds relevant governments and authorities responsible for maintaining roads/highways or, to quote the latest case of official indifference, the blatant violations of the green cracker directions by the Supreme Court in the National Capital Region. Tragically, the onus falls on the victim to pursue a tortuous case in the courts for compensation, while civic authorities hide behind the convenient and impenetrable cloak of their political masters, or mistresses, as the case may be.

—The writer is former Senior Managing Editor, India Legal magazine