By Vickram Kilpady

The linguistic reorganisation of states has been a necessary and inevitable chapter in India’s political evolution. It cannot now be dismissed as a historical mistake simply because “faith” or its euphemism “culture” might be imagined as a more cohesive national adhesive, as Tamil Nadu Governor RN Ravi recently suggested.

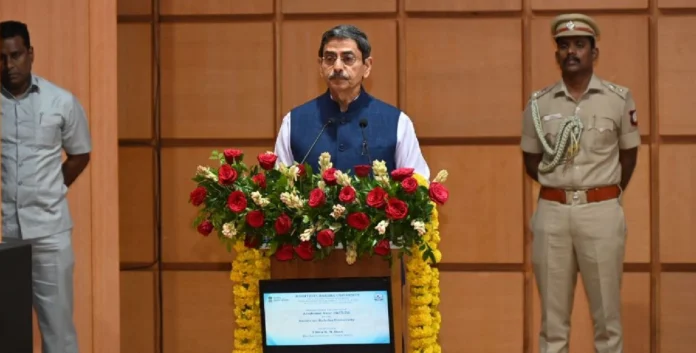

Being an IPS officer at heart, Governor Ravi is not one to mince words, even after spending nearly four years amid the quietude of Chennai’s Raj Bhavan. While most governors adopt a careful, calibrated tone—never sounding too contrarian—Ravi wears his bluntness like a badge of honour. It may also be that the constituency he speaks to prefers its messaging unvarnished.

Speaking recently at the Rashtriya Raksha University (RRU) in Gandhinagar, Gujarat, the governor declared that linguistic reorganisation was a “bad idea” that had led to the creation of “second-class citizens”. He recalled the protests that accompanied the reorganisation of states in the 1950s, suggesting that people had “refused to live with each other,” and that the fallout from these decisions fractured the collective consciousness of a 5,000-year-old “Bharat rashtra”.

Referring specifically to Tamil Nadu, Ravi claimed that people who once lived together—Marathi, Gujarati, Kannada, Telugu, Tamil and Hindi speakers—were now divided, with one-third of the population relegated to second-class status. He did add, in a rare nod to even-handedness, that this had occurred in other parts of India as well.

According to Ravi, dividing India along linguistic or ethnic lines was an assault on the nation’s spiritual unity. The implication was clear: the India that emerged after 1947 was not a new republic, but a reincarnation of an ancient, indivisible civilisational entity. And this entity, he believes, has been eroded by modern political compromises like linguistic states.

Aside from the many assumptions embedded in his argument—delivered, notably, at a university founded by Prime Minister Narendra Modi—Ravi’s speech reflects a certain flair for selective history. Because what he delivered was less a scholarly critique and more a political diatribe.

That context matters. Ravi has had several public run-ins with Tamil Nadu’s elected government, led by Chief Minister MK Stalin and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK). The DMK, part of the Opposition INDIA bloc, has consistently challenged the BJP-led centre on issues, ranging from federalism to cultural autonomy. Its latest battle has been over the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, which the DMK sees as enforcing Hindi at the cost of Tamil and English—the two-language formula Tamil Nadu has historically followed. In protest, the centre has withheld education funding.

The DMK, of course, rose to power in the 1960s precisely by opposing Hindi imposition. With state assembly elections on the horizon, Ravi’s broadside against linguistic federalism seems more than coincidental. The delimitation exercise and fears over seat redistribution may also be feeding anxieties in Tamil Nadu, further fuelling the DMK’s resistance to the centre’s centralising tendencies.

Now consider the history Ravi glosses over. The first demand for linguistic reorganisation came from Telugu speakers seeking a separate Andhra state. Potti Sreeramulu’s death after a 57-day fast in 1952 led to its creation—without the originally desired capital of Madras (now Chennai). Kurnool became the capital instead. In Bombay State, two mass movements demanded separate states for Marathi and Gujarati speakers. Yes, violence occurred. Buses were burnt. Lives were lost. But it pales in comparison to the seismic communal rupture of the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992—a wound from which India still bleeds.

The governor’s claim of “second-class citizens” doesn’t hold under scrutiny. Gujaratis in Maharashtra, or Telugus, Kannadigas, and Malayalis in Tamil Nadu have rarely, if ever, raised such a charge. Chennai remains a hub for linguistic plurality, just as Mumbai does for ethnic diversity. Cosmopolitan cities like Bengaluru and Gurugram are thriving precisely because of multi-lingual, multi-ethnic coexistence—the kind that flies in the face of Ravi’s argument.

India, born amid the trauma of Partition, was always destined to be a complex federation. What held it together wasn’t linguistic uniformity or religious homogeneity, but an honest reckoning with its breathtaking diversity. “Unity in diversity” wasn’t a hollow slogan—it was a national survival strategy. It still is.

What threatens that unity is not federalism, but a majoritarian nationalism that frames difference as deviance. The real anxieties over “outsiders” have surfaced not in linguistically drawn states, but in economic zones of migration: Goans unsettled by North Indian influx, Maharashtrians wary of Bihari and UP migrant workers. These tensions are economic and cultural, not linguistic.

Governor Ravi also took aim at ethnicity-based statehood in the Northeast, a region he knows well from his IPS years and his role in the Naga peace negotiations. Surely he must recognise that ethnic anxieties and demands for statehood were part of the Northeast’s complex post-colonial integration into the Indian Union. Meeting those demands was not a weakening of India—it was the only way to keep it whole.

Or maybe there’s another layer. As the government’s interlocutor for the Naga Peace Accord signed in 2015, Ravi may be disillusioned with its recent unravelling. The NSCN (IM) has publicly disowned the agreement, calling it a sham. Perhaps, then, the governor’s Gandhinagar speech was more personal than political—a public venting of professional frustration.

Or maybe, after years in Adyar’s leafy quiet, Governor Ravi simply longs for something more stirring than the Raj Bhavan’s stillness.