By Dr Swati Jindal Garg

Does the person filing a First Information Report (FIR) determine the outcome of the case? In a recent study that was conducted in Haryana, the results show that not only gender-based violence, but even skewed complaint redressal is a major consequence of gender inequality. Bukky Shonibare, an activist from Nigeria, has very aptly said: “When girls are valued less than boys, women less than men, they face multiple risks throughout their lives—at home, at work, at school, from their families and from strangers. Gender-based violence is a major consequence of gender inequality.”

The research project in Haryana, “Police Processes and Judicial Outcomes”, traced cases from the initial filing of FIRs to the final outcome in courts and studied over four lakh FIRs in Haryana. It found that male complainants who register cases on behalf of their woman friends or relatives are less likely to “face burdens or exclusions” than if a woman was listed as a primary complainant. Which brings us to the ultimate question: Does the gender of the person filing a FIR determine the outcome of the case?

Going by the shocking results of the study, it apparently does!

The study gathered information from 4,18,190 FIRs filed between January 2015 and November 2018 in Haryana. The cases studied ranged from theft to burglary to violence against women. The study further matched over 2.5 lakh FIRs with judicial records found on e-courts website and found that women’s complaints are less likely to go from the police station to the judiciary, and even when they finally do, there are fewer convictions—5% for women as compared to 17.9% for male complainants.

This huge gap in conviction for cases filed by men and women not only belies the perception that women often misuse protective legislations such as the domestic violence act or rape laws, which have a reverse burden of proof, but also goes to show that the women today are not getting the benefit of the laws that were created, to begin with, for their protection.

A careful analysis of the text of FIRs also found that in the complaints filed by men, the penal provisions invoked primarily relate to theft, rash driving, burglary and public intoxication/bootlegging while those filed by women mainly refer to Section 498-A of the IPC, which deals with cruelty by the husband or relatives of the husband. As if this was not enough, the study also shockingly revealed that women complaining of violence have to wait for an average of two hours longer at a police station before their FIRs can be filed and the cases are infrequently assigned to junior officers, even constables.

Not only this, on an average, a woman’s FIR registration lags almost a month behind the man’s. The situation is almost identical even in the constitutional courts wherein the dismissal of complaints filed by women, allegedly in the “heat of the moment”, is not uncommon.

In fact, the Supreme Court in Preeti Gupta & Anr vs State of Jharkhand & Anr had even stated: “It is a matter of common experience that most of these complaints (of assault and violence against women) are filed in the heat of the moment over trivial issues”. It is important to note that this case was also cited when the apex court held in another case that “misuse of the provision (489-A) is judicially acknowledged.” In Sushil Kumar Sharma vs UOI, the Supreme Court held that domestic violence provisions are “a license for unscrupulous persons to wreck personal vendetta or unleash harassment (against men), and a form of legal terrorism (by women).”

It is important to mention here that the study also found that the median days between crime and its registration is 1, with a mean of 28, but women’s cases and violence against women have means of 69 and 113, respectively. Which means that the waiting period between the day when a complaint is filed and the day on which it gets converted into an FIR is far more in women-related cases than in other cases. This challenges the assumption of the courts that most women-related cases are filed “in the heat of the moment”. The study has finally shown, in the best possible way, the true picture of how bias works against women at every stage of the redressal system—starting from the time at which a complaint is lodged in the police station to the actual final outcome, i.e. the pronouncement of its judgment.

While there is no doubt that a woman is heavily disadvantaged when accessing justice in India, it cannot be denied that it will take a long time when the system actually accepts this fact. This discrimination is even more glaring when these women-related cases that are selected to leave police jurisdiction, enter the courts for the first time. It has been found that women’s cases spend longer in the judiciary by over a month as compared to those that are filed by their male counterparts. Furthermore, cases brought forward by women are significantly more likely to yield a suspect’s acquittal as per the study, much to their disillusionment. It is also disheartening to see that women complainants seeking justice from the State have a lower chance of a suspect that wronged them being sent to prison for any complaint than their male counterparts.

The reasons for this bias are manifold. Research states that the administrators as per the study may be acting rationally, but with incomplete information. They may also hold inaccurate beliefs about women’s tendencies to exaggerate, or further, the female complainants who reach the police stations may be statistically less likely to afford lawyers or cope with in-person follow-ups necessary for trial, thereby precluding judges from making informed decisions. The actual distances from their place of residences to the courts also play a vital role in their non-participation in the trials. Another big issue is that describing certain crimes, especially those that relate to violence against women can be a little difficult for the victims.

All these reasons and more conspire towards a pattern of “multi-stage” discrimination in terms of a more onerous process and unequal outcomes for women at successive stages of seeking redressal of their problems.

Not only are the Indian women disadvantaged in terms of the police delaying the registration of their cases, they also suffer as fewer cases registered by them are sent to courts. While on the one hand they suffer delays in investigation, on the other, their cases have a higher rate of dismissal in courts. Delays in trials combined with higher rate of acquittals and lower convictions of accused all go together in decreasing the faith that these women reposed in the Indian judicial system. In the light of the fact that most of these female victims turn to formal institutions only as a last resort, the lack of help from the system breaks their spirit and alienates them from any other support that they might have been able to garner otherwise.

Most of these women have already faced a pattern of “multi-stage” discrimination in terms of a more onerous process and unequal outcomes for women at successive stages of seeking restitution, and hence, the fact that they also end up suffering immense mental and physical harassment is totally unfair. Being victims themselves, these women end up spending formidable amounts of money and resources to reach that final stage of redressal only to have their complaint dismissed and the accused let out scot free. This breaks their morale and faith in the justice delivery system.

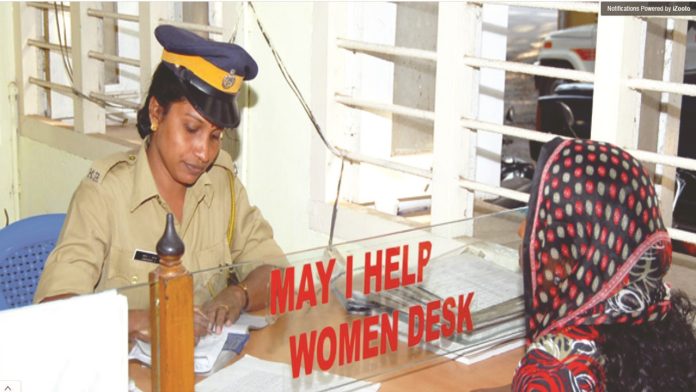

Based on the available data, simply creating more police stations (or mahila thanas) or special women’s courts or even fast-track courts is not the solution to mitigate these jarring disparities. While the legislature is handing out power to all the oppressed women, the system is taking it away from them. This appears to be more a case of ticking all the boxes without filling any of them!

While most of us are not surprised that Indian women face hardships, there are others, including the police, the judges and even the policymakers who maintain that female complainants send men to prison for frivolous offences, that the Indian Penal Code is heavily biased in the favour of women and that it is time for the men to rise for a “men’s rights movement” as an answer to the women’s “legal terrorism”. Going by the results of this latest study, can we truly say that women in India are reaping any benefits or misusing the laws that have been made for their emancipation?

My personal view is that while we are still a far cry from when we can truly say that we have come a long way, power lies in not forgetting that we are the generation of change that can change the world.

—The writer is an Advocate-on-Record practicing in the Supreme Court, Delhi High Court and all district courts and tribunals in Delhi