By Shaan Katari Libby

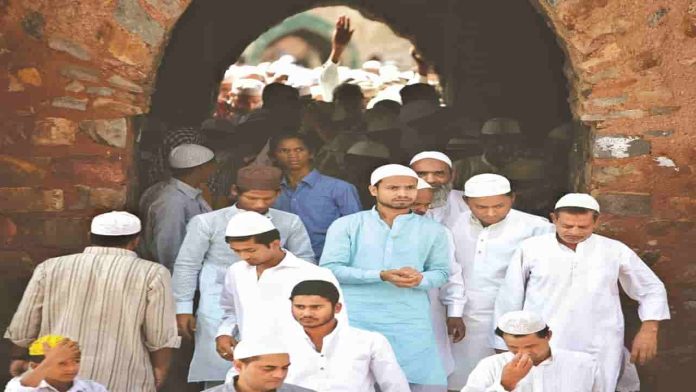

As we continue to see clashes between states and Wakf Boards, and temples wanting access to traditionally Muslim zones, religion is being increasingly used as tool. Is this what India was meant to be and how should faith-based disputes be resolved?

The World Population Review 2022 reveals that Hinduism is the most common religion in India, accounting for about 80% of the population. Islam is the second-largest religion at 13%, followed by Christians (2.3%), Sikhs (1.9%), Buddhists (0.8%) and Jains (0.4%). If the majority religion votes in a certain way for a party, it will surely come to power. Hence, using religion as a tool for votes—whether by way of endowments to religious charities or trusts or by creating hatred for others—works effectively. There will be relatively few so-called liberals who will see through such tactics and want to see more from politicians—genuine progress, vision, integrity and hard work. Even some educated people are completely taken up by the idea of a majoritarian state and politicians have cottoned onto this.

Recently, the Supreme Court ordered status quo to be maintained in the Bengaluru Idgah maidan case and said that in keeping with years past, Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations would not be held at the ground. “For 200 years it was not done, you also admit, so why not status quo, for 200 years whatever was not held, let it be,” the bench comprising Justices Indira Banerjee, AS Oka and MM Sundresh remarked. Senior Advocate Dushyant Dave appearing for the Idgah made an urgent mentioning before Chief Justice of India UU Lalit that under Section 3 of the Places of Worship Act, there was an absolute bar against conversion of use of religious land for any other religion.

In a similar, but contrasting case, the Karnataka High Court upheld permission granted by the Dharwad Municipal Commissioner to Hindu organisations for performing Ganesh Chaturthi rituals at the Idgah ground Hubbali-Dharwad. The Court stated the title of the property belonged to the Dharwad Municipality and the petitioner was only a licensee of the plot having permission to offer namaz only on Ramzan and Bakri Id. The Court further noted that there was no evidence offered for the argument proffered that the property was covered under the Places of Worship Act 1991, as the ground was also used for activities like vehicle parking and vending. The Court distinguished the Idgah ground at Chamrajpet in Bengaluru as there was a title dispute there, whereas in the Hubbali case, the Municipality held the title. The logic on the face of it seems acceptable, but there is a deeper question at play here.

What did our founding fathers intend? Tahir Mahmood rightly said in a recent article entitled “Religion, Law, and Judiciary in Modern India”: “Constitutionally, India is a secular nation, but any ‘wall of separation’ between religion and State exists neither in law nor in practice—the two can, and often do, interact and intervene in each other.” Interestingly, he makes the point that of all the SAARC countries, India is the only one without a declared official religion.

The American concept of secularism requires a complete separation of church and State, as also the French ideal of laïcité; religion is relegated entirely to the private sphere and has no place in public life. In India, our founding fathers incorporated all the basic principles of secularism into provisions of the Constitution without having the word secular in the Preamble. It was just a Sovereign Democratic Republic. According to Mahmood, this was intentional so that India did not have to adopt the afore-mentioned western notions of a secular state. Twenty-five years later, the word “secular” and “socialist” were inserted.

Indian secularism requires equal treatment of all religions without any discrimination. Article 14 states: “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.” This was coupled with Article 15 which read: “The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth, or any of them.” Article 16 says: “No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion…be ineligible for, or discriminated against, in respect of any employment or office under the State.” Article 25 states: All persons are equally entitled to “freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practice and propagate religion”. Article 26 states that every “religious denomination or any section thereof” shall have the right (a) to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes; (b) to manage its own affairs in matters of religion; (c) to own and acquire movable and immovable property; and (d) to administer such property in accordance with law.

Teaching religion is banned in wholly-funded schools. No religious instruction is to be provided in the schools wholly maintained by State funding (Article 28). Those attending any State recognised or State-aided school cannot be required to take part in any religious instruction or services without consent. Religious minorities have the right to maintain schools giving minority instruction, but no institution receiving State aid has the right to deny someone admission solely due to their religion. (Articles 29 and 30).

It is, therefore, more than apparent what our founding fathers intended for India—a truly multicultural country that was a beautiful conglomerate of multiple faiths that had respect for each other’s beliefs whilst interacting.

The British did try to protect those who converted to Christianity by introducing the Caste Disabilities Removal Act in 1850. After Independence, several states introduced laws imposing restrictions on missionary activities—examples being the Orissa Freedom of Religion Act of 1967, the Madhya Pradesh Freedom of Religion Act, 1968, and the Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Indigenous Faith Act, 1978. Recently, anti-conversion laws were enacted in various states, including Gujarat and Rajasthan.

So how should faith-based disputes be resolved? In a multi-faith country with a large mass of uneducated people, politicians are bound to use something as personal as religion to win votes.

So, what is the solution? Should politicians be making decisions or courts? The Constitution is meant to be upheld by all. It is supreme, and lawmakers should abide by it at all times, else face the threat of dismissal. Yet, Muslims seem to be at odds with the centre at every step.

The US State Department’s Religious Freedom Report 2020 spoke of the 2019 Citizenship Amendment Act which excludes Muslims from expedited naturalisation provisions granted to migrants of other faiths and how these became violent in Delhi. Bias has often been alleged against the police, who are by their very nature, creatures of the State. The report goes on to say: “Political party leaders made inflammatory public remarks or social media posts about religious minorities. Attacks on members of religious minority communities, based on allegations of cow slaughter or trade in beef, occurred throughout the year. Such ‘cow vigilantism’ included killings, assaults, and intimidation.”

Speaking to Muslim friends, one hears how some of our best and brightest are feeling unwanted, threatened and are leaving India at the earliest opportunity. They are closing their companies and letting go of employees at a time when people need employment more than anything. One hopes that the centre and courts work to end short term thinking, thus securing a future that is bright for all Indians, regardless of their faith.

—The writer is a barrister-at-law, Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, UK, and a leading advocate in Chennai. With inputs from Jumanah Kader