By Subramanyam Sridharan

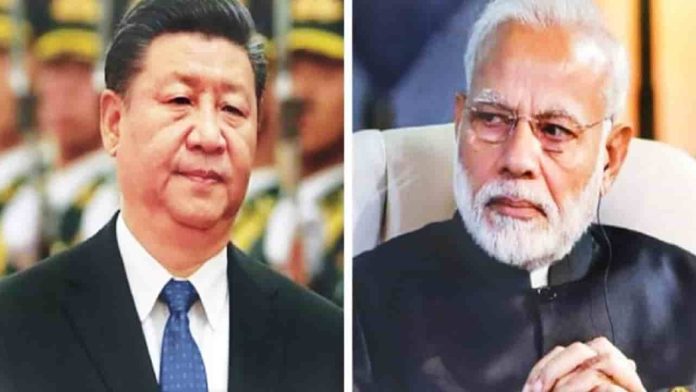

The recent fleeting engagement between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping at the BRICS meeting in Johannesburg has raised speculation whether a solution to the military confrontation in Ladakh is likely in the remaining two crucial areas of Depsang in the North and Charding Ninglung Nallah, Demchok in the South.

As India has consistently said in the last three years, the relationship would not be restored to the pre-May 2020 level so long as “status-quo ante” was not restored by China along the LAC. On the other hand, China has been trying to trivialise the border issue by claiming that Ladakh was just one aspect of the whole relationship and it should be “compartmentalized” so that the rest of the ties can grow. This line has been repeated by the then Chinese Ambassador to India Sun Wei Dong, Foreign Ministers Wang Yi and Qin Gang and Defence Minister Li Shangfu. The latter claimed that the border situation was “stable” as if no Chinese aggression ever happened and India has de-facto accepted the current position.

However, the truth today is that the political relationship between the two countries stands derailed, trade link remains restricted by India and an abnormal military situation persists with China continuing to build infrastructure and upgrading military installations along the LAC, making India respond appropriately. It is in this context that the question arises whether the meeting at Johannesburg would result in any positive movement along the LAC that could lead to a thaw in relationship eventually.

The short answer to these questions is that while China may resort to some minor tactical “concession” for some immediate reasons, the long-term prospects are just as bleak as they always have been.

Any expectation of a tactical adjustment necessitates looking into the reasons for China’s unexpected attack beginning May 2020. China’s opaqueness means that we might never know, but there can be the following few inferences. China sent a warning shot across the bow that the US and the QUAD would not come to India’s help if it decided to attack; it needed to show who the real hegemon in Asia was; it used Covid as an opportunity to do its usual salami-slicing; it wanted to settle the border issue from a position of strength; Xi Jinping wanted to divert domestic attention from an emerging pandemic catastrophe; it wanted to show India its place or “teach a lesson” etc. China pursues an “immediate punishment” regime whenever it perceives threats or slights from other nations.

Some say that there are increasingly lesser chances of the PLA being able to wage a war, at least in the near future, due to the huge economic headwinds that China is facing, its relentless demographic decline and the experiences from Galwan and Pangong Tso where kinetic action was seen as disastrous to PLA soldiers who could not match their Indian Army counterparts.

There is another school of thought which suggests that these could be all the more reasons for some kinetic action along the LAC. PLA top brass might think that in its overall scheme of things, the order of attack would have to be India and/ or Japan first, which would train its inexperienced recruits from single-child families and test the Chinese platforms, ammunition, mettle, tactics, etc., before taking on Taiwan. It might be Xi Jinping’s conclusion that a weary and hesitant US would not decisively intervene in Ladakh/Arunachal Pradesh or Senkaku issues apart from providing moral, diplomatic and a minimal military support which would not amount to much. He may feel that the Chinese campaign could be concluded quickly when the resulting fait-accompli would settle the issue and prevent a larger conflagration. China feels that diplomatically and militarily it could hold on to the gains. This is the tactic that it seems to be trying out in Depsang and Demchok and that is why the Chinese are constantly advising us to separate the border issue from other state-to-state dealings.

Taiwan and Indo-China Sea (ICS, also called South China Sea) would be an entirely different matter altogether because of the involvement of the US, Japan, South Korea, Australia, NATO et al. The Indian Navy too could seal the various choke points in the Indian Ocean Region.

Essentially, therefore, none of the Chinese reasons for the post-May 2020 attacks in Ladakh have disappeared. In fact, some of the issues since then have accentuated its worries like its steep economic downturn with no end in sight, tighter technology bans by the West, much stronger alliances emerging against China, a teetering Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a clumsy Ukraine war in which China supports its faltering “no limits” friend, Russia, etc. It is for these reasons that China wants access to the Indian market. It is China’s inability to participate in large Indian infrastructure projects that is hurting it badly. In the last three years, all Chinese ministers have almost pleaded with India at every opportunity to loosen its regulations for China’s participation in its growth. Since nothing has worked, Xi Jinping would have been left with no alternative but to offer some innocuous concessions, hoping that India would clutch them, expecting greater things to come, the usual Imperial hubris, while at the same time continuing with coercion in Ladakh.

Besides, China would like India to formulate the joint statement to its liking at the upcoming 18th Heads of State Summit of G20 in early September. This meeting is expected to see personal attendance by US President Joe Biden and Xi Jinping. In the G20 Foreign Ministers’ meeting, our foreign minister pointedly cited China and Russia as the reason for the lack of consensus for a joint statement. The Chair’s Summary had a footnote that said the two paragraphs (Paragraphs 3 and 4) in the summary about the war “were agreed to by all member countries except Russia and China”. Similarly, the finance and health ministers’ meetings also ended without joint statements for the same reason. Even G20 meetings at the bureaucratic level have ended without a joint statement.

Such a confrontational position, failing India’s conciliatory stance in the meetings, helps China in two ways. One is that it nullifies India’s efforts to create a consensus, which was possible less than ten months back at Jakarta, but not now, and therefore dents India’s role in the Global South. The second reason is that it helps in its relentless effort to displace the US from its high perch in every endeavour.

India cannot allow China to exceptionally dictate terms at the G20 meet. China’s attempts at G20 and BRICS have been to create an anti-West or at a minimum, a neutral grouping, similar to the now defunct Non-alignment Movement. These are but a continuation of Xi’s four initiatives namely, BRI, Global Security Initiative, Global Development Initiative and Global Civilizational Initiative to assume a Global South leadership role with Chinese characteristics, similar to its angling for the Asian hegemon status.

We do not know if Xi Jinping really showed any inclination in resolving the border issue during his informal meeting with Modi at Johannesburg. If he had, then the above could be the tactical reasons for that. But China is well known for playing with words, doublespeak and even lying as it did in the closed-door UNSC meeting on August 16, 2019, over the Abrogation of Article 370. Its Permanent Representative had tried to portray his country’s position as “the will of the UNSC” by taking advantage of the fact that deliberations at such meetings are not openly reported, whereas it transpired that its proposal had been rejected 14 to 1. Therefore, India has to proceed with great caution on the assumption that Xi Jinping showed a genuine intention.

On the strategic front, China is still pursuing its “China Dream” which has two components, domestic and international, with both being intertwined. Domestically, the idea is to attain the status of “fuqiang” (wealthy and powerful nation). Geopolitically, it is to attain the status of world’s sole hegemon, the Middle Kingdom mandated by Heaven, by toppling a seemingly declining US. Asia is most crucial for China’s latter ambition not only because China is geographically located here, but also because of the need to establish itself as a regional hegemon, before attempting the more difficult task.

It has not only got into many disputes, land and maritime, with several countries of the region, but is also facing resistance in its own backyard from both regional and extra-regional players. Japan, Vietnam, South Korea and the Philippines have long-term disputes with China, with Japan and Vietnam having a civilisational fear of China extending nearly two millennia. However, it is India that China fears the most because of its size and potential. In a reversal of the Thucydides Trap, the more-powerful revisionist China considers the less-powerful status-quoist India as its challenger and has been trying to contain it to the quagmire of South Asia.

Unless China abandons its ambition to be the sole global pole, an abandonment which is inconceivable because yearning for such an exalted status is culturally ingrained in the Han DNA for centuries, its enmity with its long-term strategic competitor, India, will not dissipate, but only grow and boil over eventually.

—The writer is a distinguished member of the Chennai Center for China Studies. His book Space Situation Awareness and China is in print