By Sanjay Raman Sinha

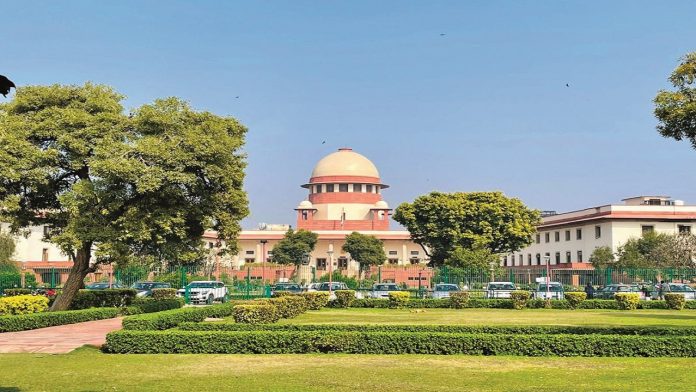

Caesar’s wife should be above suspicion. Similarly, when a judge, soon after retirement, takes up a government-offered post, eyebrows are raised and fingers pointed.

The appointment of former Supreme Court judge S Abdul Nazeer as the governor of Andhra Pradesh within 40 days of his retirement was one such instance. Justice Nazeer was part of the five-judge bench that heard the disputed Ram Janmabhoomi case and had passed a verdict in favour of the Hindu litigant party. Also, just before retirement, he had headed the bench that upheld the demonetisation policy of November 2016. Both were pro-government verdicts and his acceptance of the gubernatorial post was seen with suspicion.

Earlier, Justice Ranjan Gogoi, former chief justice of India, had accepted a nominated post in the Rajya Sabha. He had given two landmark judgments which were in favour of the government. These were the Ayodhya verdict and the Rafael one.

It has been reported that 21% of Supreme Court judges who retired in the last five years had taken up post-retirement posts. The issue of accepting such posts without a sufficient cooling off period has roiled the judiciary. The 14th Law Commission Report had proposed that judges should not take up post-retirement jobs from the government.

The core idea behind this is based on the principle of separation of powers. The independence of the judiciary is an in-built mechanism which creates a shield against abuse of power by the executive and the legislature. The judiciary is the proverbial white knight of the democratic system.

Though the concept of separation of powers is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, it has been developed as an element of the basic structure—sacrosanct and inviolable. In the Kesavananda Bharati vs State of Kerala case and later in the Indira Nehru Gandhi vs Raj Narain case, the Supreme Court had held: “Separation of Powers is a part of the basic structure of the Indian Constitution.”

The whole principle of an independent judiciary is based on the principle of separation of powers. For example, the appointment of judges through the collegium system and minimising the role of the executive is based on the necessity of maintaining the independence of the judiciary. This also explains why judicial independence became one of the most important elements of modern constitutionalism. Judges are expected to adhere to constitutional morality.

The Supreme Court has held: “Constitutional morality is the founding faith upon which the Constitution is based, it must have a value of permanence which is not subject to the fleeting fancies of time and age.” Constitutional morality means adhering to the norms of the Constitution and not act in a manner which is violative of the Rule of Law or reflects arbitrary actions.

Ronald Dworkin, professor of jurisprudence, had proposed that judicial independence and judicial morality are two wheels of a chariot. So if we expect judicial morality from judges, would it entail a life of enforced quietude and unemployment?

Interestingly, appointees to the post of Comptroller and Auditor General and chairman of the Union Public Service Commission have been constitutionally debarred from holding government posts after serving in their respective jobs. As per Article 148 (4): “The Comptroller and Auditor General shall not be eligible for further office either under the Government of India or under the Government of any State after he has ceased to hold his office.” Similarly, Article 319 (A & B) states: “The Chairman of the Union/State Public Service Commission shall be ineligible for further employment either under the Government of India or under the Government of a State.”

Studies of American courts have shown that job-retention prospects may influence the decisions of judges who are close to retirement. Incentive effects imply that judges will decide cases in ways that increase their chances of being re-employed. If judges expect to be screened based on their judicial decisions, they may consider this when rendering judgments.

It is relevant to remember the Charter called “Restatement of Values of Judicial Life” which was adopted by the Supreme Court on May 7, 1997. It is a code of judicial morals and supposed to be a guide for an independent and fair judiciary. The code comprises 16 points. The recommendations propound ethics which destroy the presence of “biasness” in judicial work.

However, implicit in the charter is the judicial purity of judges who are supposed to not only deliver unbiased justice, but should make sure the justice process and its practitioners are impartial. So is the act of declining a government-offered post by judges one such assertion of morality? The answer is not straight.

Linked with the issue of taking up posts after retirement is the retirement age of judges. The retirement age for Supreme Court judges is 65 and that of High Court judges, 62. This is often considered too early for retirement, more so because judges can ably hold tribunal and other posts effectively. Their wisdom has matured over the years and they have attained an expertise which is not easy to come by. Raising their retirement age may be one of the answers to this intractable problem.

The retirement age of judges has also been a point of concern for the government. The previous UPA government had brought a bill in 2010 where there was a proposal to increase the retirement age of High Court judges from 62 to 65 years. But this bill lapsed after the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha in 2014. This bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha, but was never discussed. Former Attorney General KK Venugopal had argued during his tenure that when lawyers who are 70-75 years can argue cases, why should Supreme Court judges retire at 65?

Justice Bhanwar Singh, former judge of the Allahabad High Court, told India Legal: “The posts of chairman and members of tribunals and commissions or equivalent judicial or semi judicial posts with any nomenclature must be filled by retiree judges of the Supreme Court and High Courts of high integrity and super merit. Judges during their long tenure learn to impart justice in accordance with law and prescribed procedure. This judicious aptitude is generally not available in personnel from other walks of life. There should be a national commission for the appointment of former judges for judicial or quasi judicial posts.”

Speaking to India Legal in one of its TV shows, Justice Narendra Chapalgaonkar, former judge of the Bombay High Court, said: “If some retired judges are willing, capable and efficient, then the chief justice of the High Court should recommend their appointment as ad hoc judges.”

Most judges support the extension of retirement age. Naturally. This can, to an extent, offset the allure of plum post retirement posts. Nonetheless, those who take up government offered jobs should not be seen with suspicion. After all, in the absence of any code of ethics, it is an individual decision and should be seen entirely in isolation and merit.