By Shaan Katari Libby

“Four things belong to a judge: To hear courteously; to answer wisely, to consider soberly and to decide impartially.”

—Socrates, Circa 400 BC

These words resonate today as the Supreme Court collegium headed by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud reiterates its decision to appoint five advocates as High Court judges. One of them includes Saurabh Kirpal whose sexual orientation and his “foreign-national” partner were sticking issues. How fair is it and what about courts abroad? Do sexual orientations matter there?

Socrates’ words are sacrosanct, and selecting judges is the subject of much disagreement in India. Recent events with the Executive returning the collegium’s recommendations once again owing to sexuality and independent thought appear to have brought things to a head.

As a normal course, the president appoints High Court and Supreme Court judges after consultation with other judges of the Supreme Court and some High Courts. An apex court judge retires at 65 years (62 for High Court judges).

Saurabh Kirpal being denied a berth in the High Court judiciary because of his sexual orientation flies in the face of Article 15 of the Constitution of India which states: “The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or any of them.” Article (16) states: “There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters relating to employment or appointment to any office under the State” and “No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, residence or any of them, be ineligible for, or discriminated against…”

Judges are already in a relative position of weakness—their ultimate paymaster is Parliament. As per the Department of Justice website, salaries, pensions and allowances of Supreme Court judges are charged on the Consolidated Fund of India. All revenues and loans received by the government by way of taxes are credited to the Consolidated Fund under Article 266 (1) of the Constitution and no amount can be withdrawn from the Fund without authorisation from Parliament.

Delving into history, the Three Judges cases are relevant here. The First Judges Case (S.P. Gupta vs President Of India And Ors) held that there was primacy of the central government in deciding on judges: “consultation is different from consentaneity (i.e. consent by all). They may discuss but may disagree; they may confer but may not concur”. It would, therefore, be open to the government to override the opinion: “Where there is a difference of opinion amongst the constitutional functionaries who are consulted, it is for the Central Government to decide whose opinion should be accepted and whether appointment should be made or not.”

The Second Judges case (Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Assn. vs Union of India) finding was “on the question of primacy, the court concludes that the role of the Chief Justice of India in the matter of appointment of the Judges of the Supreme Court is unique, singular and primal, but participatory vis-a-vis the executive on a level of togetherness and mutuality, and neither he nor the executive can push through an appointment in derogation of the wishes of the other”. SP Gupta’s case insofar as the issue of “primacy” is concerned was overruled.

The Third Judges case was more of a reference question than a case. It was opined here that for the appointment of puisne judges of the Supreme Court of India, the opinion of the chief justice has primacy in the consultative process. The collegium should comprise the CJI and four seniormost judges of the Supreme Court. Views of relevant High Court judges should also be consulted. None would be appointed if the CJI dissented. The CJI has the discretion to disclose reasons for non-appointment.

Of late, we have had long waiting periods between when judges are recommended to the government and when they are actually confirmed. Also, names proposed by the collegium are returned for reconsideration. This laborious game has led to a shortage of judges contributing to a system where even the simplest of cases takes years to close.

As far as selection goes, we all know of excellent lawyer candidates who have been passed over. And there are some who are approached who don’t accept the post because they do not relish a stressful period of years of uncertainty before they get elevated as judges. For instance, Kirpal waited four years—luckily he has age on his side—but many don’t.

Purely on the point of appointment of a homosexual judge, a point of comparison might be the appointment of Justice Edwin Cameron of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. Edwin Cameron was born in 1953 in Pretoria. He was a lecturer in Latin and Classical Studies before he left for Oxford in 1976, on a Rhodes scholarship. He began practice as a lawyer at the Johannesburg Bar in 1983, was instrumental in the gay and lesbian movements and appointed on a permanent basis to the High Court in 1995 and in 2000 to the Supreme Court.

To be a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom as per the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, there is a clear application procedure for those interested. Those applying need to have held “high judicial office for at least two years”. “Alternatively, applicants must have been a qualifying practitioner for at least 15 years.”

For other judges, there is the Judicial Appointments Commission (JAC)—an independent commission that selects candidates for judicial office on merit through fair and open competition from the widest range of eligible candidates. JAC is an executive non-departmental public body, sponsored by the Ministry of Justice.

The UK is, in fact, looking to increase judicial diversity. There are currently several programmes that are designed to assist eligible candidates considering a career in judicial office. Representation today in the UK judicial services remains as quite small with the Ministry of Justice’s 2020 statistics report showing that 6% of applicants that year were openly LGBT+ (3).

A few prominent examples include Sir Adrian Fulford who entered the judiciary in 1995 rising as judge for the International Criminal Court. In 2009, Sir Fulford spoke on “Against the Odds: A celebration of equality and diversity” about the problematic attitudes he encountered back in the 1990s and how he felt things had changed.

In his valedictory speech, as the outgoing Master of the Rolls and as Britain’s most senior openly gay judge, Sir Terence Etherton spoke about promising himself that he would never hide his sexuality, what representation in the judiciary meant to him and how he hoped he was leaving the state of access to justice more improved than when he entered the profession.

The first openly trans person to be appointed a High Court judge was Dr Victoria McCloud, a barrister.

Switching now to the US: the president wields great power when it comes to the appointment of judges. Recommendations come from the Department of Justice, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, members of the Congress, sitting judges and Justices and the American Bar Association. Some judicial hopefuls even nominate themselves.

A powerful tradition of senatorial courtesy involves the senators from the state in which the vacancy occurs making the decision. A senator of the same political party as the president sends a nomination to the president, who almost always follows the recommendation.

Despite a strong traditionalist base in America, candidates have not been deprived of allotment on the basis of sexual orientation. The first state with an LGBT Justice was Oregon, where Rives Kistler was named to the bench in 2003. Approximate figures suggest there are now 75 to 100 openly gay judges, most of them in California, New York and Chicago. Gay and lesbian judges do not appear to have had a particular impact on gay-rights issues. However, gay men and lesbians on the bench help diversify the judiciary.

Senior Counsel Sriram Panchu who has written on the matter in the mainstream media, had proposed a compromise consisting of 3:2 collegium (Judiciary: Executive). When asked specifically about the rejection on the basis of sexual preferences, his response was: “How does it (sexuality) matter? It brings diversity to the Bench. One ought not to deny anybody a seat.” He suggested that in the long run, India needs a Judicial Commission which will search wider: “Lawyers at NGOs, Academics…they should pool in the names and then have this process…”

Should lawyers who are interested to be judges simply apply for the post—filling a standard application form—just as they do in lower courts here and at all levels in the UK? After the applications are considered and culled, some could be interviewed and appointed. It would also save time. Panchu agreed that an application process could be put in place so that suitable candidates apply.

Something drastic is needed—and fast—as it is simply not practical for litigants’ lives and those of would-be judges to be kept on hold while names get shuffled back and forth from one department desk to another. India can do better.

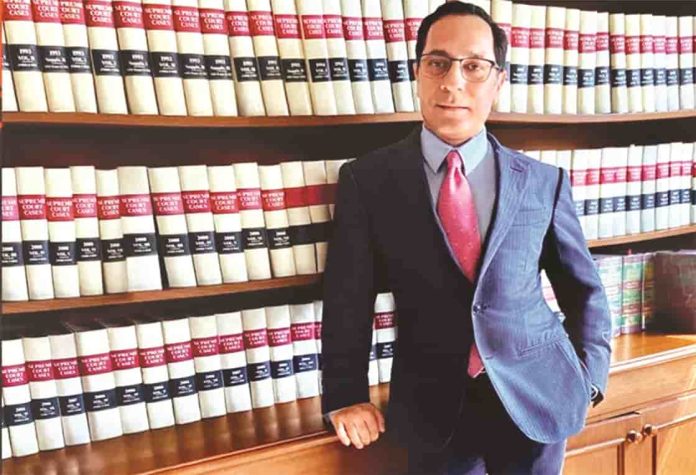

—The writer is a barrister-at-law, Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, UK, and a leading advocate in Chennai. With research inputs from Mahesh P Sudhakaran and Sibani Suresh