“I am at a loss to understand as to how the activity of the children in helping their parents in selling pens and other small articles would amount to child labour…” observed Justice VG Arun of the Kerala High Court on January 6, while directing the release of two children from Delhi who were sent to a shelter home on the grounds that they were being forced into child labour by selling articles on the streets. The parents of both the children are natives of Rajasthan and had migrated to Delhi in search of livelihood. Compelled by impecunious circumstances and inclement weather, they move to Kerala for a few months every year and eke out a living by selling pens, chains, bangles, rings, etc. The children accompany the elders in selling their wares on the streets. On November 29, 2022, the children were taken from their parents by the SHO, Central Police Station, alleging that they were being forced to do child labour by selling articles on the streets. The children were produced before the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) and sent to a shelter at Palluruthy, Kochi in Kerala.

The innocent children have been languishing in the shelter since then, away from the care and safety of their parents and the company of their siblings. The petition was filed by their parents seeking a direction to the respondents to release both children to the custody of the petitioners (parents of both the children).

On December 30, 2022, the CWC was directed by the High Court to file a statement explaining as to why the custody of the children cannot be given to the petitioners. Accordingly, a statement was filed which said that while conducting a search operation on November 29, 2022, the police saw both the children involved in selling pens and other articles in the Marine Drive area. The children were taken before the CWC. On finding that both would come under the category of children in need of care and protection as stipulated in Section 2(14) (i)(ii) of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, the CWC ordered the children to be placed under the care and protection of the shelter home.

Thereafter, an inquiry was conducted, which revealed that the petitioners and the children are permanent residents of South Delhi and are presently residing in a single room dwelling in City Lodge in Iyyattu Junction in Ernakulam. It was also stated that, being of the opinion that, for their benefit and holistic development, the children should live and grow in their own culture, the CWC passed an order under Section 95 of the Act, to send the children to CWC, District South East, New Delhi for rehabilitation.

While considering the matter, the single judge bench of Justice Arun observed: “No doubt, the children ought to be educated, rather than being allowed to loiter on the streets along with their parents. On interaction with the petitioners, they undertook not to let the children on to the streets for selling articles and to take measures for educating them. I wonder as to how the children can be provided proper education while their parents are leading a nomadic life. Even then, the police or the CWC cannot take the children into custody and keep them away from their parents. To be poor is not a crime and to quote the father of our nation, poverty is the worst form of violence.”

As per the general principles to be followed in the administration of the Juvenile Justice Act, the best interest principle requires all decisions regarding children to be based on the primary consideration that they are in the best interest of the child and to help the child develop to full potential. Thus, under the principle of family responsibility, the primary responsibility of care, nurture and protection of the child is that of the biological family. Therefore, the holistic development of both children cannot be attained by separating them from their biological family. On the contrary, the attempt of the State should be to provide the children with proper education, opportunity and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity, said the High Court.

In another recent judgment of January 5, the Telangana High Court noted that where a juvenile who works voluntarily, Sections 75 and 79 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2005, did not apply. A single judge bench of Justice K Surender quashed the proceedings for the offences under Sections 75 and 79 of the Act.

Section 75 of the Act says: “Whoever, having the actual charge of, or control over a child, assaults, abandons, abuses, exposes or willfully neglects the child or causes or procures the child to be assaulted, abandoned, abused, exposed or neglected in a manner likely to cause such child unnecessary mental or physical suffering, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to three years or with fine of one lakh rupees or with both:

Provided that in case it is found that such abandonment of the child by the biological parents is due to circumstances beyond their control, it shall be presumed that such abandonment is not willful and the penal provisions of this Section shall not apply in such cases:

Further, if such offence is committed by any person employed by or managing an organisation which is entrusted with the care and protection of the child, they shall be punished with rigorous imprisonment which may extend up to five years, and fine which may extend up to five lakh rupees:

Provided also that on account of the aforesaid cruelty, if the child is physically incapacitated or develops a mental illness or is rendered mentally unfit to perform regular tasks or has risk to life or limb, such person shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment, not less than three years but which may be extended up to ten years and shall also be liable to fine of five lakhs rupees.”

Section 79 deals with exploitation of a child employee. It says that….whoever ostensibly engages a child and keeps him in bondage for the purpose of employment or withholds his earnings or uses such earning for his own purposes shall be punishable with rigorous imprisonment for a term which may extend to five years and shall also be liable to fine of one lakh rupees. Explanation—for the purposes of this Section, the term “employment” shall also include selling goods and services, and entertainment in public places for economic gain.”

To sustain prosecution under Section 26 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, the prosecution must have a definite allegation that a minor boy or girl was subjected to hazardous employment with the object of exploitation. The essential elements to constitute the offence under Section 26 of the Act, are that a minor child was subjected to some hazardous employment, without paying any wages, or without making payment of proper and adequate wages. Besides the element of being subjected to hazardous employment, there must also be the other important essential element of exploitation to attract the prosecution under Section 26, the Kerala High Court observed in the case of Ramla Chalil vs Sub Inspector of Police.

The Delhi High Court on November 22, 2022, directed the Delhi government to de-seal a property which was sealed last year after it was found that the tenant had engaged children for his tailoring business while observing that the landlord cannot be made to suffer indefinitely due to misconduct of the tenant. It is pertinent to note that in 2020, a civil judge in Uttarakhand was dismissed from service for allegedly torturing a minor girl who worked as a domestic help at her residence.

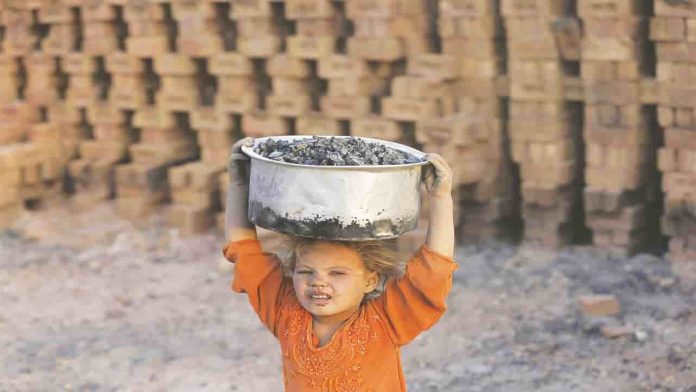

A significant proportion of children in India are engaged in child labour. Bonded child labour is a system of forced labour under which the child or child’s parents enter into an agreement with a creditor. In 1977, the Union government passed a legislation that prohibits solicitation or use of bonded labour, including children.

As the Kerala High Court decision indicates, interpretation of various aspects of the law regarding child labour tends to vary and can have unfortunate outcomes.

—By Shivam Sharma and India Legal Bureau