By Binny Yadav

In a major push towards this goal, the Union Ministry of Law and Justice has issued a comprehensive Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) titled, “Directive for the Efficient and Effective Management of Litigation by Government of India.” The SOP lays down guidelines for all central ministries and departments to reduce and better manage litigation involving the government. It’s a long-overdue intervention—but will it be enough?

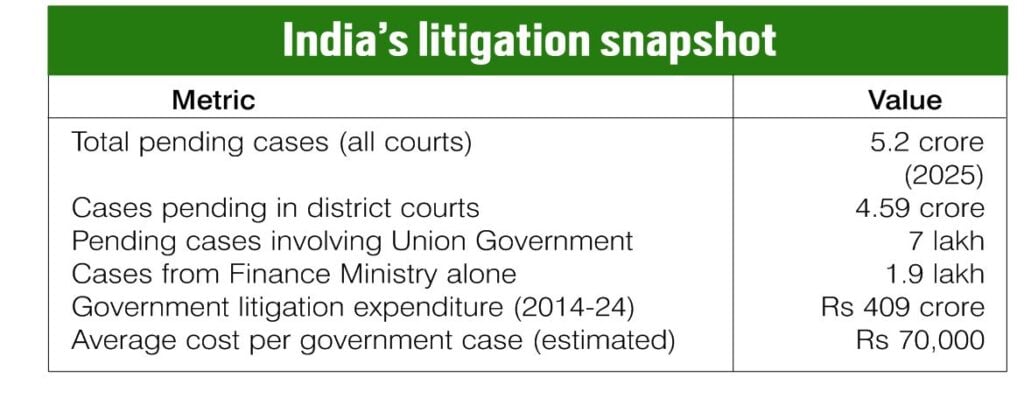

INDIA’S LEGAL BACKLOG: THE NUMBERS TELL A STORY

The judiciary’s burden is staggering:

- 5.2 crore-plus total pending cases (as of mid-2025).

- 4.59 crore cases are stuck in lower and taluk courts.

- The government is party to nearly 50 percent of all litigation.

States like Uttar Pradesh alone have over 1.2 crore pending cases. The government’s role as a habitual litigant—appealing nearly every adverse ruling, regardless of merit—has contributed significantly to the judicial logjam.

This isn’t just a matter of numbers. Every delayed case represents a pension unpaid, a land dispute unresolved, or a taxpayer’s money wasted on repetitive legal filings. Citizens bear the brunt of a government that has often prioritised litigation over resolution.

THE REAL-WORLD FALLOUT: HOW CITIZENS SUFFER

Take the case of retired railway employees, some of whom wait decades for pension disputes to resolve because departments escalate minor clerical issues through multiple appeals. In Maharashtra, over 2,000 land acquisition cases involving farmers remain unresolved years after acquisition—often because of inter-departmental wrangles. Even appeals in tax matters, sometimes involving amounts as low as Rs 500, clog the system simply because departments reflexively challenge every tribunal ruling.

These aren’t isolated cases. They reflect a systemic inertia where government departments prefer litigation over accountability, even when the cost—financial or human—is high.

WHAT THE NEW SOP AIMS TO FIX

The SOP issued by the Law Ministry marks a strategic shift. It aims to curb the government’s instinctive tendency to litigate and instead promote responsible legal conduct. The key highlights include:

1. Early Legal Advice: Departments are instructed to seek legal opinions at the inception of disputes, not after escalation. This could prevent avoidable court cases.

2. Prioritise Alternative Dispute Resolution: The SOP mandates serious consideration of mediation, arbitration, or conciliation—particularly in service and contractual disputes.

3. Strategic Filing and Appeals: No longer can departments automatically file appeals. They must now assess public interest, legal sustainability, and financial cost before pursuing further litigation.

4. Inter-Departmental Coordination: Ministries must avoid conflicting positions in court. A single coordinated legal stance is to be maintained, especially in complex issues involving multiple departments.

5. Officer Accountability: For the first time, officers can be held personally responsible for lapses—including failure to act in time, poor briefing of counsel, or escalation of frivolous cases.

6. Proactive Engagement with Legal Counsel: Departments must ensure timely communication and briefings for government lawyers—avoiding last-minute litigation strategies that often weaken the government’s case.

7. Digital Litigation Monitoring: A unified litigation monitoring platform is being developed to track government cases in real time, analyse trends, and flag wasteful or repetitive filings.

WHAT’S AT STAKE: MONEY, TIME, AND TRUST

According to official data, the central government spent Rs 409 crore on litigation between 2014 and 2015 and 2023 and 2024—including Rs 66 crore in the last year alone. A Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy study estimates that the government spends roughly Rs 70,000 per case, factoring in legal fees, administrative costs, and time. Furthermore, of the seven lakh pending cases involving the Union government, a staggering 1.9 lakh relate to the Ministry of Finance alone.

This is public money—and its diversion towards needless litigation erodes trust and reduces funds available for development.

IMPLEMENTATION HURDLES: CULTURE VS REGULATION

Policy reform, however, isn’t enough. Several challenges remain:

- Fear of audits discourages bureaucrats from settling cases.

- Lack of legal training in administrative services.

- No clear incentives for avoiding litigation.

- Weak enforcement of accountability mechanisms.

Experts argue for training officers in legal decision-making, establishing clear KPIs for dispute resolution, and creating public dashboards to track SOP compliance.

POLICY AT A CROSSROADS

The SOP by the Law Ministry is a progressive and necessary step—but only its implementation will determine whether it becomes transformative or toothless.

If the government begins to litigate less and resolve more, it could dramatically reduce judicial burden, restore faith in governance, and ease the lives of millions of citizens entangled in legal battles.

Justice delayed is justice denied. But with the right reforms—and the will to enforce them—justice can still be delivered.

—The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist, lawyer and trained mediator