By Prof Upendra Baxi

Forum shopping in defamation cases has become widely known as “libel tourism”—a term coined by human rights barrister Geoffrey Robertson. The veteran human rights defender launched the libel law reform campaign, which in 2009 attacked the British Press Complaints Council, a self-regulatory body, as merely a “confidence trick” that had failed in its basic tasks of acting as “a poor person’s libel court”. Robertson was unsparing in adding the observation that UK’s “archaic laws—which date back to Victorian times”—amounted to a principle of “very expensive speech” rather than “free speech”.

And the chilling effects on freedom of individual speech and media freedom of expression have been well documented. For example, the UN Special Rapporteur in her 2013 report expressed grave concern about the prevalence of defamation laws and the consolidation of “sophisticated forms of impeding the work of human rights defenders”. And in the EU, an anti-SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation—a corporate governance tactic) movement has urged legislation to protect investigative journalists, independent media and human rights and human rights activists.

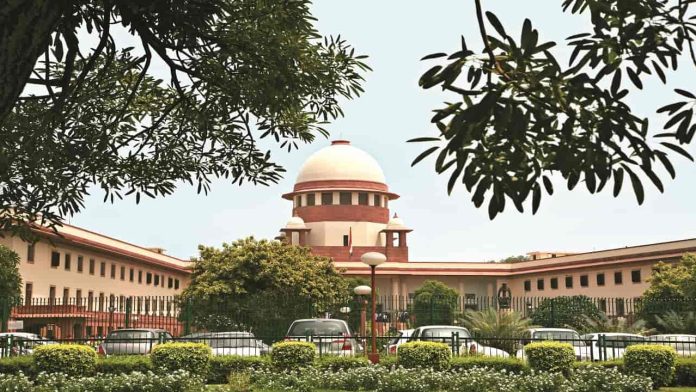

The Supreme Court of India has now its own golden opportunity to heal the wounds of libel tourism. Justice Surya Kant and Justice Dipankar Datta have issued a “notice” while hearing an appeal (on August 13, 2023) decided by Justices SS Sundar and PB Balaji of the Madras High Court in Advantage Strategic Consulting Singapore Private Limited vs Dr. Subramanian Swamy [(2023)4 Madras Law Journal Vol 355 at 206-226]. This decision reversed a single bench decision which allowed Dr Swamy an anti-suit injunction. An anti-suit injunction, simply put, orders a party either not to commence or not to take any further steps in proceedings in another jurisdiction.

The Singapore Company was admittedly a company which was operating in Singapore and it was alleged by them that in the expose of the alleged illegalities in the Aircel-Maxis’ deal, “several defamatory allegations and remarks were made by the plaintiff against the appellant/Company and its operations in Singapore to impress that the appellant is a completely illegal Company with the sole intention of defaming the appellant”. Alleging substantial damage to its reputation and loss of business in Singapore, a suit was filed by the appellant before the High Court of Singapore.

Some two decades earlier, the Supreme Court propounded that an anti-suit injunction was to be granted “sparingly” and only when three conditions were met. First, the defendant, against whom the injunction is sought, is amenable to the personal jurisdiction of the court; second, if the injunction is declined, the ends of justice will be defeated and injustice will be perpetuated; and third, the principle of comity—respect for the court in which the commencement or continuance of action/proceeding is so sought (to be restrained—must be borne in mind. [See, Modi International Case, cited in Para 16 of the MLR].

While the first criterion is a matter of evidence, the same cannot be said of the second and third criterion, which, while clear enough in the abstract, lead to immense value judgments in the concrete contexts, as the differences among the learned single justice and Division Bench in this case show. How are, in the instant case, we to reconcile the conflicted values—those of duties of justice on the one hand, and state or international comity on the other? Are the ends of justice well served by lifting the corporate veil so as to give an anti-suit injunction (as was done by the learned single justice) or by letting a foreign court decide on a libel suit (as accomplished by the Division Bench)? What ends of “justice” are served, we may ask, by the “comity” of nations in a digital era?

An essential requirement for libel is proof of publication now stands complicated by publication in foreign jurisdiction by way of social media news and views. What happens when the comments are originally published in one place via a press conference, but stand excerpted or copied and published in social media sites which may be accessible worldwide? Ought the human rights standard of “informed consent” be transposed to the digital world of social media?

It is, of course, for the concerned courts to decide whether the publication occurred at home or overseas or across the globe! But does not any decision concerning an anti-suit injunction require some prima facie substantive jurisdictional connection and higher thresholds of harm caused by the publication? Should disclosure by social media by persons not connected at all with the original place of publication enable choice of any foreign forum? May we covert the doctrine of anti-suit jurisdiction into a roaming global venture of libel tourism?

Perhaps, freedom of speech may be strengthened by some new age laws such as passed by England and Wales by the 2013 Defamation Act, which incorporates steps to avoid the chilling effect on free speech. It entails now the requirement of “serious harm threshold”, protection for scientists and academics for publishing peer-reviewed material in learned journals; defense of reasonable belief that speech is in the public interest; a new process to help potential victims of defamation online and “single-publication rule” to prevent multiple claims in different jurisdictions on the same matter.

Space does not allow any review of Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita Bill, 2023 (“BNS”), now being considered by a parliamentary committee, but it is interesting to note that BNS (in its very penultimate sections) retains the robust regime of defamation provided in Chapter 21of the “colonial” IPC that includes both libel and slander. The BNS here forgoes the opportunity of reconsidering criminal defamation (which has been judicially or legislatively abolished in many countries). How the three “codes” seeking to replace the IPC, the Criminal Procedure Code, or the Indian Evidence Act impact on judicial power relating to anti-suit injunctions remains to be seen.

In any event, the Indian Supreme Court has never in the past hesitated in providing via suggestive jurisprudence fresh legislative starts and some normative illumination on proposed reforms (for example, the law relating to sexual harassment, gender justice, sustainable environment, and the right to information). Whether it will seek to do so now for situations of libel tourism remains an agonizingly open question.

—The author is an internationally-renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer