By Sanjay Raman Sinha

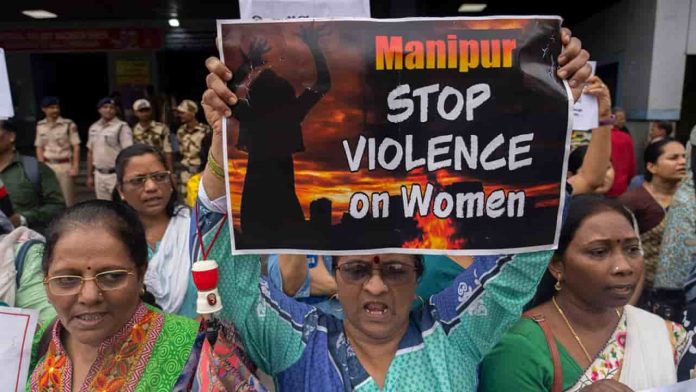

As inter-tribal violence seared the beautiful state of Manipur, the shocking video of two women paraded naked on the streets by a frenzied mob shook the conscience of the nation. Amid the nationwide uproar, questions were raised about the National Commission for Women (NCW) and what it did to mollify matters.

According to media reports, incidents of sexual violence against women in Manipur were reported to the NCW by two women activists and a civil society organisation called the North American Manipur Tribal Association in June, a month before the troubling video became public. NCW chief Rekha Sharma said that before the video surfaced, they were informed by several groups about such heinous crimes happening in the state. There was not one specific complaint, but many, both from the state and outside the state.

Later on, the NCW condemned the Manipur incident. Taking suo motu cognizance, the DGP of Manipur has been asked to promptly take appropriate action. The NCW also directed Twitter India’s Head of Public Policy to remove the objectionable video as it compromises the identities of the women and is a punishable offense.

Despite Manipur being a matrilineal society which prides women as the head of the social unit, crimes against them continue unabated. A Women Action Development report recorded a total of 191 cases of crime against women in 2022. The report indicates a rise in rape and missing cases in the same year. The Manipur State Commission for Women also registered as many as 78 cases of crime against women in 2022. It also received the highest number of domestic violence cases in the same period.

In 2014, a delegation of NCW led by Mamta Sharma, then chairperson, visited Manipur to apprise the state commission’s performance. The delegation was told by the state unit that they were unable to do productive and meaningful work as per the mandate because of problems faced by them. Some of the problems enumerated by them were: SCWs have very small budgets which are not sufficient to cater to the needs of women in the area. Funds were also grossly insufficient for holding legal awareness.

Police sensitisation is needed to ensure cooperation from their personnel. More fast track courts are needed to provide justice to women. Compulsory self defense training for girls should be introduced so that girls can protect themselves. More shelter homes for girls are required. Gender budgeting should be introduced in the state’s budget to ensure funds for women-related issues and programmes.

The setting up of NCW was a result of years of lobbying by women’s groups and a follow-up of the National Perspective Plan for Women. Increased participation of women in the national arena came as a result of the women’s movement and the need to expand constituencies by political parties. But even as women were mobilised, their genuine demands were ignored. Their political participation suffered and women’s cause became more a symbol than substance.

The “parent ministry” of the Commission is the Ministry of Women and Child Development, but the Commission interacts closely with other ministries too. The Commission’s mandate is “to review the Constitutional and legal safeguards for women, recommend remedial legislative measures, facilitate redressal of grievances and advise the government on all policy matters affecting women”. As per law, the Commission consists of: “A Chairperson, committed to the cause of women, to be nominated by the central government and five members to be nominated by the government from amongst persons of ability, integrity…’’ As the chairperson and members are government nominees, it becomes difficult for them to voice concerns which go against the government. It can’t be over-critical of the government either.

Ironically, Manipur is one of the India’s last matrilineal societies where women control property and inheritance and have a presence in public spaces. There have been women-led social movements in Manipur such as the Nupi Lan of 1976, the historic Kangla fort protest and the protest of Irom Chanu Sharmila against the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. These have strengthened the view that Manipur is a robust feminist society where empowered women rule the roost. However, sociological studies have shown the contrary. Matrilineal structures have women as centre points, but there is a subtle male dominance that runs unseen beneath all social norms. This hidden male dominance has been termed as “benevolent patriarchy” which wields “pastoral power and disciplinary power over women”.

There are certain customs in the Meitei society that promote a preference for sons. Women who bear sons are held in higher regard in their immediate families and locality. Continuation of bloodline via a male heir is deemed important. As elsewhere, working womenfolk are expected to do household chores as well as their professional work. The male can easily shrug off household chores. Though there are multiple responsibilities for Manipuri women, male dominance persists. Incidents of Manipuri women exploitation could spring from these hidden male dominance founts.

In this sociological framework, the role of women commissions gains importance as they can hand-hold women to lead them towards an equitable society. Though the Commission lacks penal power, it can advise government on policy matters—“Investigate and examine all matters relating to the safeguards provided for women under the Constitution and other laws. Look into complaints and take suo motu notice of matters relating to deprivation of women’s rights….”

Recently, the Manipur High Court held that the state women’s commission is empowered to issue arrest warrant at the stage of inquiry and the commission has the power of a civil court to summon and ensure attendance of any person from any part of India. The commission is mandated to propose policy changes as it impacts women.

The Commission has been proactive on the issue of child marriage, Dowry Prohibition Act, PNDT Act, the Indian Penal Code and the National Commission for Women Act, 1990. However, in Manipur, there has been a complete breakdown of law and order. Apart from the tribal conflict, there is the issue of Rohingya influx, leading to allegations of a foreign hand to explain the lawlessness in the state.

These matters need state intervention. The Women’s Commission can at best work at the grassroots level to nurture traditional social norms, increase awareness of women’s rights, take up exploitation matters and coordinate with the government to facilitate protection of women’s rights. But even that is not happening, allege critics.