While expressing deep concern over the increasing number of deaths due to manual cleaning of sewers in India, the Supreme Court said that “the unforgettable annals of our history not only have charted the numerous sacrifices of the people who fought for independence from the foreign imperial ruler but also a lesser-known freedom that for millennia eluded a large mass of people, who were nearly invisible. They were trapped in the thralldom of a solitude from which there was no liberation. That was centuries old stigmatising social practices that led to their deprivation, to such levels that they were not even recognised as human beings. Among these practices was one which generations of people were made to perform the meanest task of manual scavenging…”

The bench of Justices S Ravindra Bhat and Justice Aravind Kumar made this observation in its order while hearing a public interest litigation filed by one Balram Singh, who objected to the employment of manual scavengers.

The bench further said that “it was to address this kind of social practice and with the resolve to completely out light and emancipate those trapped in it from the thralldom of bondage, that the constitution framers ensured three important provisions, which stare at us like beacons, assuring not only equality but fraternity amongst all people: the prohibition of untouchability; the outlawing of forced or involuntary labour and the freedom against exploitation.”

The bench further said that “to flesh out and give shape to the objects of these provisions, Parliament intervened and enacted several legislations. The first was the Civil Rights Act 1955; its provisions were amended in 1976 to outlaw the practice of untouchability. The penalization of these severe forms with stringent punishment was sought to be achieved by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, which was further strengthened by later amendments. In that ensuring full economic freedom and true emancipation were two enactments, the ‘Employment of Manual Scavengers and Construction of Dry Latrines (Prohibition) Act, 1993’ and the ‘Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013’.”

The bench observed that “in 1993, a special Commission for Safai Karamchari was established under the provisions of National Commission for Safai Karamchari Act, 1993… to give its recommendations to the Government regarding specific programmes for the welfare of Safai Karamcharis. In the same year, India took another significant step by prohibiting the employment of manual scavengers responsible for the daily manual emptying of certain types of dry toilets. Subsequently, the Parliament enacted the Act of 2013 which extended and clarified its scope to include insanitary latrines, ditches and pits. However, the petitioner claims that the respondents have not implemented essential provisions of these statutes. Regrettably, manual scavenging persists despite these legislations…”

The Court said “the petitioner prayed that the Act of 1993 and 2013 should be implemented in letter and spirit and to do so, it is necessary to impose a blanket ban on manual scavenging, while simultaneously ensuring adequate rehabilitation and employment opportunities for those currently engaged in these practices.”

The Court observed that the 2013 Act not only criminalizes manual scavenging, but also provides for rehabilitation mechanisms to ensure that manual scavengers are emancipated. Chapter IV of the Act, titled, “Identification of Manual Scavengers in Urban and Rural Areas and their Rehabilitation” spans from Sections 11 to 16 and is an entire code in so far as rehabilitation is concerned. The first step towards rehabilitation that the 2013 Act makes, is the identification of manual scavengers through a survey. This survey is under Section 11 for municipalities and Section 14 for panchayats. Rule 3 of the 2013 Rules begins with the words, “no person shall be allowed to clean a sewer manually with the protective gear and safety devices under these rules except …” A scrutiny of the exceptions under the rule reveals that the situations are only where mechanical equipment cannot be put into operation or when the sewer is not yet operational. In other words, the 2013 Act and rules intends that no person should have to come in direct contact with human excreta and that protective gear and cleaning devices must be provided to ensure this. The protective gear and cleaning devices required to be prescribed under the rules would also be required to be in furtherance with this purpose. That is to say, the prescribing authority must keep in mind that the protective gear and cleaning devices given to a hazardous cleaner ensure that he does not come into contact with human excreta.

The apex court observed that the liberative nature of the statute coupled with the objectives of Articles 17 and 23 require entitlements to be given to the families of those persons who died while working in sewers or septic tanks. This is also because the entire family would be rendered without a bread-winner. The economic and social status of the already downtrodden and oppressed family would dwindle further. The dignity of the individual, guaranteed by law under Article, must be ensured through rehabilitative processes. However, mere economic measures would not suffice in the upliftment of the family. Rehabilitation would require elements of long-term and short-term socio-economic measures such as scholarships, etc.

To this end, the Court found that the entitlements which are akin to those given to manual scavengers must be granted to families of hazardous workers who had died in sewers and septic tanks. In addition to the families of the hazardous workers, endeavours must be made to rehabilitate such persons who continue to be employed as hazardous workers without any protective gear or cleaning devices. States must suitably frame policies to ensure that all hazardous workers are given access to rehabilitative entitlements, the Court said.

The Court, therefore, directed the Union, the states and the Union territories to ensure that full rehabilitation (including employment to the next of kin, education to the wards and skill training) measures are taken in respect of sewage workers and those who die. It further directed the Union and the states to ensure that the compensation for sewer deaths is increased (given that the previous amount fixed, i.e, Rs 10 lakh), and made applicable from 1993. The bench said that the current equivalent of that amount is Rs 30 lakh and this shall be the amount paid by the concerned agency—the Union, the Union territory or the states as the case may be. In other words, the compensation for sewer deaths shall be Rs 30 lakh. The bench further said that in the event, dependents of any victim have not been paid such amount, the above amount shall be payable to them. Furthermore, this shall be the amount to be hereafter paid, as compensation.

Likewise, the Court also directed that in the case of sewer victims suffering from disabilities, depending upon the severity of disabilities, the compensation shall be disbursed. However, the minimum compensation shall not be less than Rs 10 lakh. If the disability is permanent, and renders the victim economically helpless, the compensation shall not be less than Rs 20 lakh, the bench said.

The bench stated in its order that “if we are to be truly equal, in all respects the commitment that the constitution makers gave to all sections of the society, by entrenching emancipatory provisions, such as Articles 15 (2), 17, 23 and 24, each of us must live up to its promise. The Union and the States are duty bound to ensure that the practice of manual scavenging is completely eradicated. Each of us owe it to this large segment of our population, who have remained unseen, unheard and muted, in bondage, systematically trapped in inhumane conditions. The conferment of entitlements and placement of obligations upon the Union and the states, through express prohibitions in the constitution, and provisions of the 2013 Act, mean that they are obliged to give real meaning to them, and implement the provisions in the letter and spirit. Upon all of us citizens lie, the duty of realizing true fraternity, which is at the root of these injunctions.”

The bench further stated that “not without reason does our Constitution place great emphasis on the value of dignity and fraternity, for without these two all other liberties are chimera, a promise of unreality. It is all of us who today proudly bask in the achievements of our republic, who have to awake and arise, so that the darkness which has been the fate of generations of our people is dispelled, and they enjoy all those freedoms, and justice (social, economic and political) that we take for granted.”

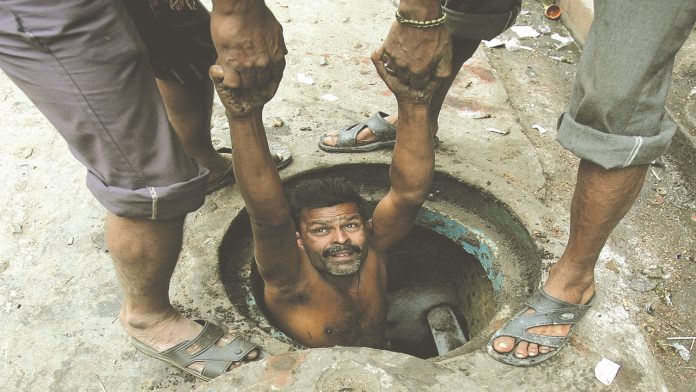

Regrettably, manual scavenging persists despite court orders and legislations.

—By Adarsh Kumar and India Legal Bureau