By Sanjay Raman Sinha

In a landmark judgment, the Supreme Court ruled that a Muslim woman can seek maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Mohd. Abdul Samad vs The State of Telangana).

The two-judge bench of Justice BV Nagarathna and Justice Augustine George Masih held that the provision applied to all married women irrespective of their religion. The verdict was a reaffirmation of the Court’s stand on the historical Shah Bano case judgment on alimony to Muslim women.

However, the crucial legal question here is: With the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986 in place, can Muslim women seek maintenance under the Code of Criminal Procedure? In this case, the wife had filed a criminal FIR against her husband, who then proceeded with talaq, resulting in their divorce. The husband claimed to have sent a lump sum for maintenance during the iddat period, which the wife refused. The wife sought interim maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC, which the Family Court granted. The High Court reduced the amount, but did not quash the order, leading the husband to seek relief from the Supreme Court.

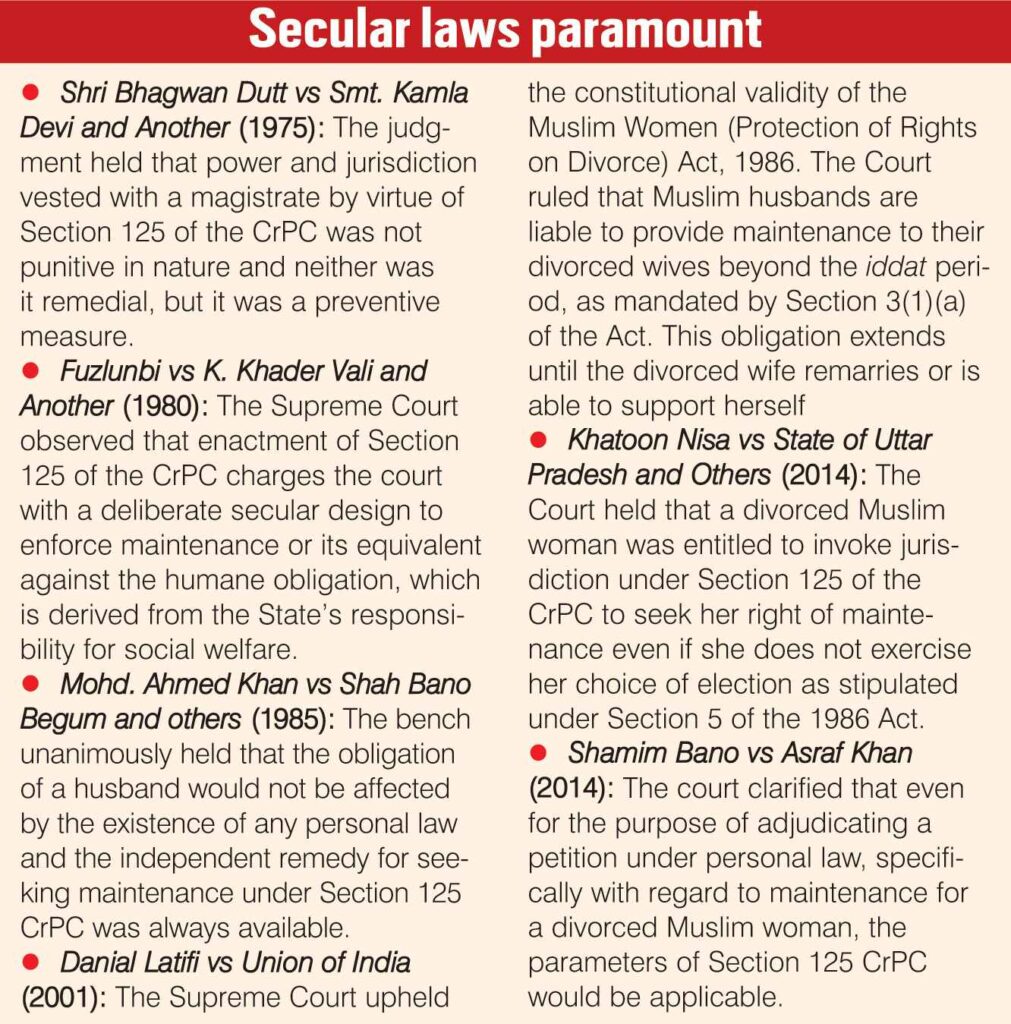

The Supreme Court unequivocally stated that a divorced Muslim woman can seek maintenance under the secular provisions of the CrPC, despite the 1986 law provisions. This decision addressed an important question about the interplay between secular law and Muslim personal law. It also highlighted the fact that a jurisprudence exists which grants Muslim women an additional right or recourse to maintenance in Section 125 of the CrPC, independent of the Muslim law provisions as defined in Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986.

In India, maintenance is governed by both civil law and personal laws of different religious communities. The laws intersect each other and there have often been legal conflicts over complexities of these two laws pertaining to the issue of maintenance.

Criminal Procedure Code Section 125 provides for speedy, effective and just remedy against persons who neglect or refuse to maintain their wives, children and parents. The Section applies to wives belonging to any religion. It has no relationship with personal laws of the parties.

Earlier, the matter of maintenance was dealt with Section 488 CrPC, which was designed to maintain wife and children and prevent their vagrancy and willful neglect. But this provision didn’t apply after divorce as maintenance was not provided for by the Muslim law. A Muslim husband could avoid law simply by divorcing his wife, who was left in most cases, penniless.

In the 1970s when the old Criminal Procedure Code 1898 was to be refurbished, women’s organisations brought representation to change Section 488 of the Criminal Procedure Code 1898 to provide protection and relief to divorced women.

An amendment was brought as Section 125 (which is equivalent to Section 488 of the 1898 code) added a new definitional clause defining the word “wife” in the context of maintenance. Here, “wife includes a woman who has been divorced by or has obtained a divorce from her husband and has not remarried”. Under this provision, the magistrate would be authorised to order an ex-husband to pay maintenance to his impoverished ex-wife who was unable to maintain herself and the extra-judicial and unilateral talaq would no longer suffice to exonerate a Muslim husband from his responsibilities.

As per Muslim law, after divorce, the wife is entitled to maintenance during the period of iddat. On the expiration of the iddat after talaq, the wife’s right to maintenance ceases.

Under Section 125 of the 1974 code, a historic case for rights of Muslim women divorced by talaq reached the Supreme Court (Mohd. Ahmed Khan vs Shah Bano Begum and others.) This was an appeal by the husband from the verdict of the Madhya Pradesh High Court directing him to pay his divorced wife Rs 179 per month as maintenance. The 62-year-old Muslim woman, Shah Bano, was disowned by her husband who had taken a younger wife. When Bano asked for maintenance from her husband, he instantly divorced her through triple talaq. Bano subsequently filed a petition for maintenance under Section 125 of the CrPC. Her petition was upheld by the family court of Indore and also by the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

The local court ordered Rs 25 per month; this was later increased to Rs 179.20 by the High Court. The husband had then appealed to the Supreme Court where he contended that he had fulfilled his responsibilities of maintenance as per the Muslim law and now as she was divorced, she was not his responsibility.

The matter was heard by a five-judge bench of then Chief Justice YV Chandrachud and Justices Rangnath Misra, DA Desai, O Chinnappa Reddy and ES Venkataramiah. The Supreme Court in a unanimous decision dismissed the appeal and upheld the verdict of the High Court. The bench held that “there is no conflict between the provisions of Section 125 and those of the Muslim Personal Law on the question of the Muslim husband’s obligation to provide maintenance for a divorced wife who is unable to maintain herself”.

The bench held that even assuming there was a conflict between the secular and personal law provisions with regard to maintenance being sought by a divorced wife, secular laws would override personal laws. Justice YV Chandrachud wrote in his verdict: “It is also a matter of regret that Article 44 of our Constitution has remained a dead letter. There is no evidence of any official activity for framing a common civil code for the country. A common civil code will help the cause of national integration by removing disparate loyalties to laws which have conflicting ideologies.”

The verdict was protested by a section of Muslims, and the ruling Congress Party was forced to nullify the judgment by an act of Parliament. In 1986, Parliament passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986, which diluted the Shah Bano judgment. The Act allowed maintenance to a divorced Muslim woman only during the period of iddat, or till 90 days after the divorce, as per the provisions of Islamic law.

The constitutional validity of this Act was challenged before the Supreme Court in Danial Latifi & Anr vs Union Of India by Daniel Latifi in 2001. The Supreme Court upheld the validity of the Act and held that a husband is under legal obligation to provide reasonable provision to the divorced wife within the iddat period and also for her entire lifetime or until she remarries.

This interpretation ensured that the Act was not in contravention of Article 14 (equality before law) and Article 21 (protection of life and personal liberty) of the Constitution. Various verdicts have underlined the fact that Section 125 of the CrPC is an instrument for social justice to protect the weaker sections, irrespective of personal laws of the concerned parties.

The complexities of Muslim law spring from the fact that it is based on the Holy Quran. The Quran is at once a religious

text and a guide for social living for the Muslim community. Islamic law as described by the Holy Quran envisages universal social and spiritual principles. The injunctions in the Holy Quran can only to an extent be interpreted by the judiciary. The judges have to depend on the interpretation of Quranic verses as provided by scholars. This is one handicap the judiciary faces while reinterpreting Muslim law and defining legal codes.

However, the touchstone on which religious laws needs to be tested is whether they are in consonance with the secular principles of justice and equality as envisaged by the Constitution. Regarding maintenance, courts have unequivocally affirmed that civil law overrides the religious code.