By Mark D Martin

India is the world’s largest aviation market by size and percentage of the travelling public. The galloping speed at which this market is expanding comes with its dark side. As airlines expand and buy more planes, pilots, the work horses of these organisations, are being put under increasing pressure to fly relentlessly. In a profession where there is zero tolerance for error, mental health issues are cropping up among pilots, impairing their ability to work and perform their DGCA mandated tasks. And trivializing this as pilot fatigue would be wrong.

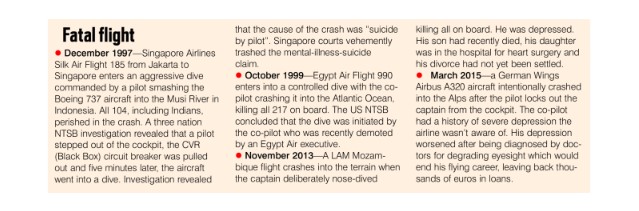

What may seem as a glamorous, flamboyant, stylish and overpaid job hides the fact that it comes with strict rules, be it rigorous medical examinations, tight deadlines and ruthless cycles that push human endurance and proficiency. This is coupled with a carrot and stick policy by airlines, each of which is racing against rivals for more passenger footfalls. This has often led to stress, fatigue and mental health issues among pilots, culminating in suicides in extreme cases (see box).

So how can this grave issue be tackled and by whom? It would be in the fitness of things for the Supreme Court and the government to enact laws and set up an independent committee urgently comprising of the mental health practitioners, psychologists and psychiatrists to screen and resolve crew stress, fatigue and work anxiety issues. Else, an air disaster may be waiting to happen. And let us keep airlines and employers out of this panel; they aren’t the competent authority to decide this considering that in many cases that they themselves are the transgressor and offender.

Articles and YouTube videos by psychologists repeatedly warn us that those with mental illness don’t even know they have it; those who know they have it don’t want to admit it and those that admit they need help, are too scared to seek it. So it is not out of the ordinary to hear the colleagues of such pilots saying: “I saw him before his flight, he seemed fine” or “We flew the night before, he was ok”.

So why is a pilot stressed? Let’s start with the facts. A pilot often has a load of pressure on him. It is an expensive passion to pursue. It costs around Rs 2 crore to be a pilot with 2,000 flight hours to be even considered by the best airlines today. Most pilots who don’t have that kind of money end up signing a five-year bond to cover the training costs. This effectively means that he is enslaved to an airline’s whims, fancies and salary cuts till the point of a burnout.

It doesn’t end there. Almost everything connected with becoming a pilot is openly linked to corruption and kickbacks. This includes getting a radio license (a pre-requisite for getting a commercial pilot’s license) and dubious “pilot-programmes”. And once a job is in hand, the struggle just gets harder—stringent yearly medicals conducted either by air force doctors or private ones, regular simulator sessions, surprise breathalyzer tests before flights and constant proficiency checks. If that wasn’t enough, there are family pressures and loans to pay off and instability in their careers due to airlines bleeding.

In my 29-year-old aviation career, I’ve managed pilots at six airlines (Bangladesh’s GMG Airlines; SkyJets Tanzania; RwandAir; Eastern SkyJets, Dubai; TAROM in Romania and SpiceJet), and it’s not been easy. There is often anxiety, depression and silent screams for help by pilots and cabin crew. This transforms into aggression and violent attacks on airline staff that are difficult to comprehend. This also manifests itself as substance abuse, alcoholism, broken marriages and children going astray.

Staying away for long hours from their homes in hotels adds to the feeling of being alienated. They can’t talk to anyone because there is no one to talk or share these problems with. By the time these aviators get home, it is past everyone’s bedtime. Like the crew bag, they take their problems with them—zipped up. This takes its toll. A Qatar Airways cabin crew killed herself in Doha by jumping off a balcony. She was lonely.

In 2015, I lost a dear American pilot friend who flew with me at Rwanda Air on the CRJ200 to self-harm and suicide during a layover. During his final moments, his ex-girlfriend and a few friends tried to step in with help. It was too late. RIP, Tailwinds Dave.

Starting with World War II, Vietnam War and the Gulf Wars, mental illnesses have been downplayed and dismissed. Soldiers that often went on a killing spree or killed themselves were termed under a condition called “Battle-Fatigue”. Britannica Dictionary’s definition of “Battle Fatigue” is a mental illness caused by the negative (sic) experiences of fighting/work in a war and that causes extreme feelings of nervousness and depression. Any guesses why we’re calling this “Pilot-Fatigue”? But that would be trivializing the problem. It’s widely known that airlines are intentionally downplaying this, but this would eventually hit them hard.

This must be corrected. The world got a taste of reality after three pilots died recently while on duty, including one who collapsed in India just before a flight due to cardiac arrest. Airlines in India today have a sizable amount of crew becoming medically unfit and several reporting sick and unable to operate flights. This is leading to increased duty hours on other rostered line pilots, with some flying into minimum crew rest that includes the two-hour cab ride to the hotel or airport. Instead of looking at this rationally by means of basic human intervention, some airlines are leaving the rostering to software to plan what’s best through an algorithm.

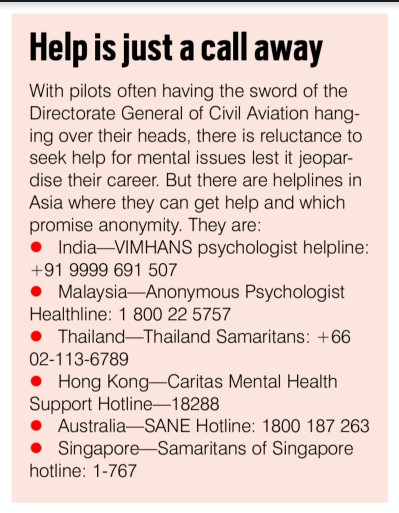

Pilots too should seek help from various helplines such as that of VIMHANS. It’s confidential. They should know that they are not alone in dealing with this. Two COVID lockdowns have led to a rough patch among pilots and airlines. With less flying, pilots and other airline staff had a difficult time.

With things looking up now, all I can do is wish them—Fly Safe and Happy Landings.

—The writer is CEO and Founder of Martin Consulting, an aviation safety & consulting firm based in Gurgaon. He is a member of the Royal Aeronautical Society, United Kingdom. The views expressed are personal.