By Vikram Kilpady

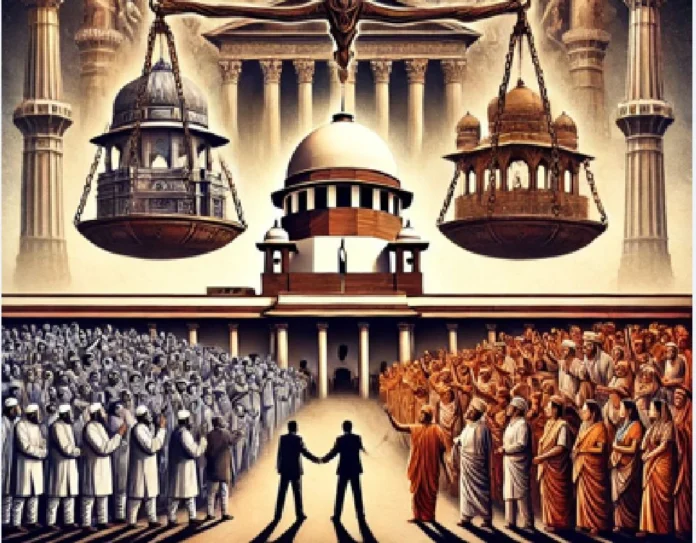

When the Chief Justice of India (CJI) says “enough is enough,” it signals a breaking point. Courts do not typically discourage petitions, for justice cannot be held hostage to an already burdened legal system. But in the case of the Places of Worship Act (Special Provisions) 1991, Chief Justice Sanjiv Khanna had to step in. Hearing fresh challenges and interventions related to the Act, CJI Khanna declared: “Enough is enough. There has to be an end to this.”

The mounting number of petitions and interventions had made the case unwieldy. The bench, originally scheduled to hear the matter in March, pushed it to April and decided it required a three-judge bench instead of the existing two-judge panel (comprising CJI Khanna and Justice Sanjay Kumar).

Adding to the complexity was the absence of an affidavit from the Government of India, despite eight hearings on the matter. The first challenge to the Act emerged soon after the 2019 Ayodhya verdict, and new petitions continued to introduce fresh legal arguments. The Court dismissed pending petitions without notice, but left room for refiling if they raised new legal points.

Now, with the centre given four weeks to file its affidavit, the Supreme Court has scheduled the hearing for the first week of April 2025.

The Places Of Worship Act: A Legal And Communal Flashpoint

The Places of Worship Act, 1991, introduced during Prime Minister Narasimha Rao’s tenure, was designed to prevent further religious conflicts after the Babri Masjid issue. It mandated that the religious character of places of worship remain as they were on August 15, 1947, barring the Ayodhya dispute, which was already in litigation at the time.

Since then, the Act has been at the heart of disputes over mosques allegedly built atop ancient temples. Calls for its repeal gained momentum after the Supreme Court’s 2019 verdict in the Ayodhya case, which granted the site to Hindus. The Ram Temple now stands where Babri Masjid once did.

The primary petition against the Act, filed in October 2020 by advocate Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay, sought to invalidate Sections 2, 3 and 4, arguing they violate:

- Article 14—Equality before law.

- Article 15—Prohibition of discrimination based on religion.

- Article 21—Protection of life and personal liberty.

- Article 25—Freedom of conscience and religion.

- Article 26 – Right to manage religious affairs.

- Article 29 – Protection of minority interests.

Upadhyay’s core argument is that the Act prevents Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs from reclaiming sites of worship unlawfully taken by past invaders, thereby ensuring that historical injustices remain unchallenged. “The Act arbitrarily sets August 15, 1947, as a cut-off date, denying legal remedies for illegal encroachments on places of worship.”

Ironically, Upadhyay was also among those who challenged the inclusion of the words “secular” and “socialist” in the Constitution’s Preamble—a plea rejected by the Supreme Court on November 11, 2024.

The Growing Political And Legal Storm

As the case gained traction, more political parties, religious groups, and intellectuals joined in—both for and against the Act. Among its staunch defenders are:

- Congress

- CPI & CPI (M)

- AIMIM (All India Majlis-e-Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen)

- Legislators from NCP (Sharad Pawar faction), RJD, and VCK

They argue that the Act is a pillar of secularism, national harmony, and constitutional integrity. Supporters also cite the Ayodhya judgment, which described the Act as a “non-derogable obligation to uphold India’s secular fabric”.

On the other hand, right-wing groups see the Act as an obstacle to religious justice, claiming it protects structures established through historical conquest and forced conversions. The illegal acts of past invaders cannot be legitimized forever under the guise of secularism.

A Nationwide Ripple Effect

While the Supreme Court deliberates on the constitutionality of the Act, lower courts have seen a surge in temple reclamation cases. In December 2024, the apex court instructed civil courts not to register fresh petitions related to temple claims, particularly in Uttar Pradesh and other sensitive states.

This move was prompted by a wave of new cases, including:

- The Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvapi Mosque dispute.

- The Mathura Sri Krishna Janmabhoomi-Shahi Idgah Mosque case.

- The Sambhal Shahi Jama Masjid controversy.

Even RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat urged caution, recognizing the potential for communal unrest. “After the construction of the Ram Mandir, some people think they can become leaders of Hindus by raking up similar issues in new places. This is not acceptable.”

The Centre’s Silence: A Political Tightrope

Despite repeated Supreme Court notices, the centre has yet to clarify its stand on the Act. Solicitor General Tushar Mehta has requested more time, citing the need for an exhaustive response. The government’s dilemma is clear:

1. Supporting the petitioners could alienate its allies and contradict its “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas” vision.

2. Defending the Act could provoke backlash from its core Hindu nationalist base, leading to an existential crisis for right-wing politics. Walking this tightrope is like balancing over a lit tinderbox.

The outcome of this case will not only shape India’s legal landscape, but also redefine the nation’s delicate balance between faith, law and secularism.

For now, all eyes are on April 2025, when the Supreme Court will determine the fate of the Places of Worship Act—and perhaps, the future of India’s religious discourse.