By Sanjay Raman Sinha

The issue of frivolous PILs has plagued courts time and again. Despite warnings, these continue to crowd various courts. Recently, the Delhi High Court took matter into its own hands and imposed a fine of Rs 1 lakh on a woman for filing a PIL against a relative when she had claimed no personal interest in the matter.

Courts have come down heavily on petitioners who masqueraded their “personal interest litigation” as public interest litigation. The Supreme Court has, over the years, dismissed various PILs for their frivolousness.

On July 4, 2023, a bench led by Chief Justice DY Chandrachud dismissed four consecutive PILs and condemned the “abuse of process” before the apex court. On June 3, 2022, a PIL petitioner was fined by the apex court for indulging in “luxury litigation” by questioning the Odisha government’s construction activity around Jagannath temple in Puri. These have continued despite Solicitor General Tushar Mehta on April 3, 2020, saying that “professional PIL shops” must be locked down. On February 10, 2017, the Supreme Court fined RJD MLA Ravindra Singh Rs 10 lakh for wasting “precious judicial time” through a frivolous PIL.

PIL was originally conceived as a means for socially conscious individuals and organisations to bring matters of public concern to the court’s attention. It was meant to serve as a tool for the underprivileged and marginalised to access justice.

The People’s Union for Democratic Rights & Others vs Union of India & Others verdict said: “Public interest litigation is a cooperative or collaborative effort by the petitioner, the State of public authority and the judiciary to secure observance of constitutional or basic human rights, benefits and privileges upon poor, downtrodden and vulnerable sections of the society.”

With the passage of time, the noble aim of PIL has been used for narrow personal gains, making the judiciary sit up and pass strictures. Frivolous petitions not only eat into the precious time of the judiciary, but they subterfuge the judicial system as well.

In Tehseen Poonawalla vs Union of India case of 2018 in which the petitioners sought an inquiry into the circumstances of the death of Brijgopal Harikishan Loya (Justice Loya), Justice DY Chandrachud wrote scathingly: “The misuse of public interest litigation is a serious matter of concern for the judicial process. Both this court and the High Courts are flooded with litigation and are burdened by arrears. Frivolous or motivated petitions, ostensibly invoking the public interest detract from the time and attention which courts must devote to genuine causes. It is a travesty of justice for the resources of the legal system to be consumed by an avalanche of misdirected petitions purportedly filed in the public interest which, upon due scrutiny, are found to promote a personal, business or political agenda. This has spawned an industry of vested interests in litigation. There is a grave danger if this state of affairs is allowed to continue…”

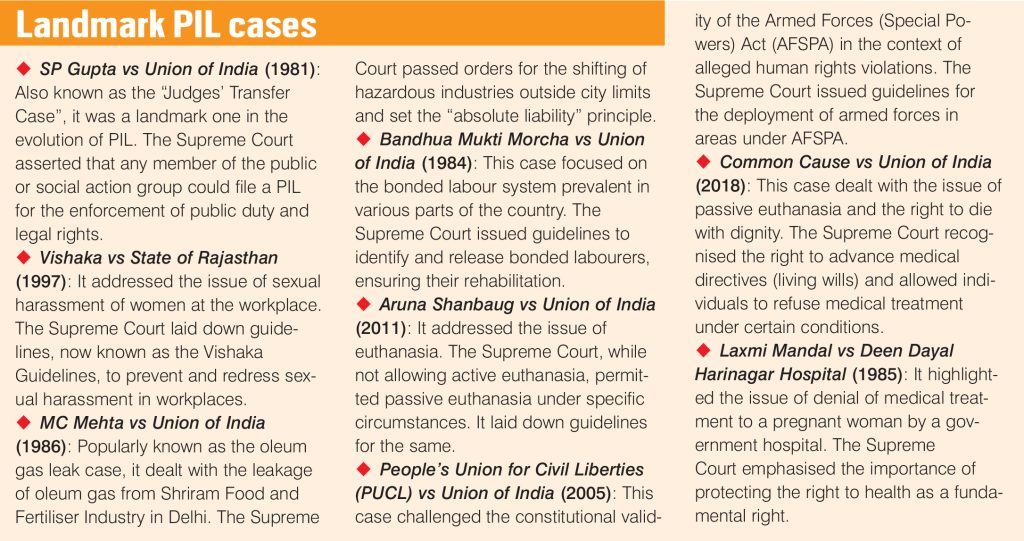

The seeds of the PIL movement were sown way back in 1979 in the Hussainara Khatoon case wherein a writ of habeas was filed for the release of a large number of men, women and children who were in jails for years awaiting trial. Their period of incarceration far exceeded their presumed punishment of a few months. The bench had ordered the release of the hapless masses on bail and Justice PN Bhagwati had then written: “It would not be enough merely to establish more courts… but to make it an effective instrument for reaching justice to the large masses.”

A few years later in 1981 in SP Gupta vs President of India And Ors case, Justice Bhagwati developed the concept of PIL. Justice Bhagwati wrote: “We would, therefore, hold that any member of the public having sufficient interest can maintain an action for judicial redress for public injury arising from breach of public duty or from violation of some provision of the Constitution or the law and seek enforcement of such public duty.”

Raising the issue of justice for a class or mass of people by someone else was then a departure from the established norms of then-extant jurisprudence. Initially, it was seen akin to class action suit of the West wherein legal action is filed by one or more individuals on behalf of a larger group of people who have similar legal claims. However, the social aim of PIL separated it from the class action suit paradigm of the West. PIL is not in the nature of adversary litigation, but essentially a tool to help deprived and vulnerable sections access social and economic justice.

In 1981, in Akhil Bharatiya Soshit Karamchari Sangh (Railway) vs Union of India case, the Supreme Court underlined the changing matrix of jurisprudence. It said: “We have no hesitation in holding that the narrow concepts of ‘cause of action’, ‘person aggrieved’ and individual litigation are becoming obsolescent in some jurisdictions.”

The PIL movement essentially evolved through three phases. In the first phase, the protection of the fundamental rights of marginalised groups who can’t approach courts gained precedence. In the second phase, cases relating to protection, preservation of ecology and environment were dealt with prominently. In the third phase, directions were issued by courts for good governance.

Along with the development of PIL, the concept of locus standi also changed. Locus standi refers to the legal right or standing of a party to bring a lawsuit or participate in legal proceedings. Locus standi is crucial because it helps ensure that only those with a direct interest to a legal dispute are allowed to bring a case before the court.

The decisions of the Supreme Court in the 1970s relaxed the strict locus standi requirements to permit filing of petitions on behalf of marginalised and deprived sections of the society by non related individuals. In the process, High Courts and the Supreme Court exercised wide powers given to them under Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution. This made judicial activism more pronounced and courts actively intervened in dispensing justice.

Alongside, suo motu proceedings got a fillip. The spirited judiciary, enthused by the new found tool for social justice, initiated PIL actions and revived petitions through suo motu proceedings.

However, the misuse of PIL never abated. Whether it was to settle business or political scores or for personal vendetta, PIL was an often used method. The vigilant judiciary continuously separated the wheat from the chaff and reprimanded the opportunity seeker. Justice Chandrachud said in the Tehseen Poonawalla case: “This will happen when the agency of the court is utilised to settle extra-judicial scores. Business rivalries have to be resolved in a competitive market for goods and services. Political rivalries have to be resolved in the great hall of democracy when the electorate votes its representatives in and out of office.”

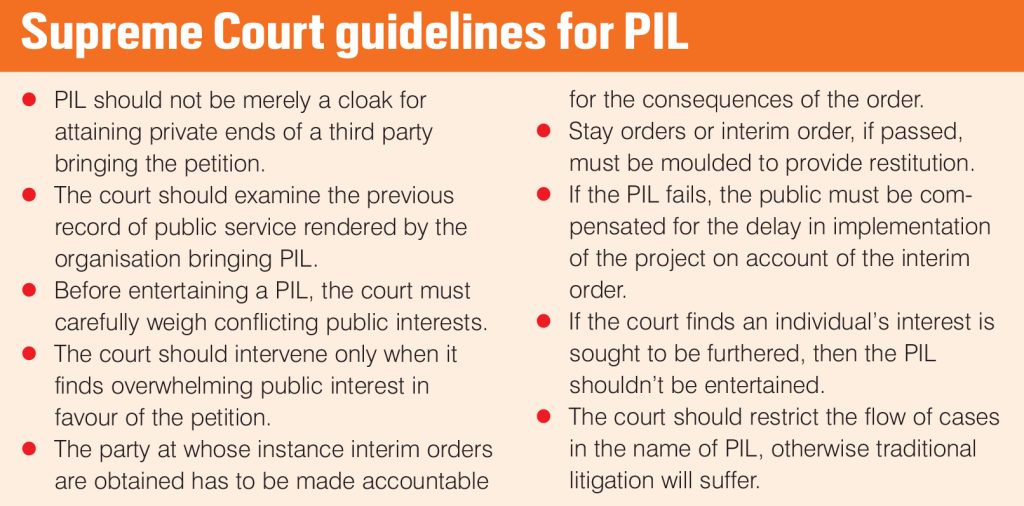

Way back in 2002, the Supreme Court in the Balwant Singh Chaufal case had felt the need for a judicial policy on frivolous PILs. It had stated: “Instead of every individual judge devising his own procedure for dealing with the public interest litigation, it would be appropriate for each High Court to properly formulate rules for encouraging the genuine PIL and discouraging the PIL filed with oblique motives. Consequently, we request that the High Courts who have not yet framed the rules, should frame the rules within three months.”

Later on, detailed remedial measures were suggested by the apex court with the aim of curbing frivolous PILs. In Raunaq International Ltd vs IVR Construction Ltd and Malik Brothers vs Narendra Dadhich case of 1999, the apex court laid down guidelines to prevent misuse of PIL. The measures were exhaustive and included checking the motive of PIL and antecedents of the petitioner. It also made it incumbent for the court to not entertain the petition if an ulterior motive was seen to serve the interests of an individual or organisation.

Legal scholar Professor Upendra Baxi, while speaking to India Legal on the problem of vexatious litigation and misuse of PIL, said: “The Supreme Court in a number of decisions frowned on ‘misuse’ of public interest litigation, which I distinguish from social action litigation. The directions, and action taken under these, are quite adequate. There has been no evidence of systemic misuse. And the Court has wisely devised a doctrine which says that ‘misuse’ of any power, process, or provision is no ground for not conferring these in the first place.”

The touchstone of preventive action against spurious PILs is strong and over the years, it has been observed that courts have been very circumspect in dealing with them. Stray deviant cases which creep up to the unsuspecting judge are nipped in the bud.

PILs should be supportive to the cause of justice to the masses and not weapons in the hands of those with vested interests.