By Sujit Bhar

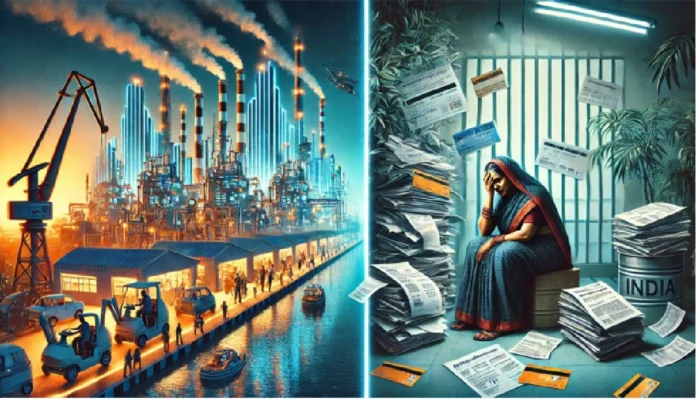

As the world, led by the US, struggles to avoid a looming recession, protectionist trade barriers and major immigrant crises that have been the result of incessant conflicts around the globe, India seems to have completely lost the plot. Not only is India being forced by the US to reduce many tariff barriers that had traditionally given research-adverse Indian companies some breathing space, its own Make in India misadventure is virtually spinning out of control and unbearable debt is choking up to 10 percent of India’s middle class.

The above is a scenario that is playing out, over and above a complete lack of social cohesion around the country where we have become obsessed with unfortunate events dating back to 300 years or even 700 years. Economists and historians alike have pointed out that these were classic methods used by the late Roman emperors to fool the semi-starving public into believing the publicised eternal stature of the grandeur of their empire which in any case was in decline. Finally, the raucous chariot races or the gladiatorial exhibitions failed to feed or clothe the people. When the mask was finally torn off, it was too late.

The Manufacturing Myth

Manufacturing can be measured in its absolute value, a somewhat misleading parameter, or in per capita manufacturing output, that gives a better picture of what the manufacturing strength of a company or country really is. Thus, while India’s manufacturing output shows growth in absolute terms, where India remains a laggard is in the per capita output. India’s distribution of manufacturing units is also poor, according to a market expert, says a report.

The manufacturing unit distribution matrix is important to gauge the social development of a country wanting to transition to a developed economy from a poor Third World system. The report points out that 52 percent of all factories in India crowd just five states: Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Karnataka, within which Tamil Nadu leads the pack with a 16 percent share. This inequitable distribution of manufacturing capacity in the country shows how skewed will social and economic development remain.

A look at the World Bank’s 2024 normalized estimates presents a quizzical picture. If one carelessly studies India’s figures in isolation, one would find that India has been ranked as the sixth-largest manufacturing nation in the world. The value-added capacity of India’s manufacturing is $450 billion. That is a fabulous sales pitch for any government, till one cares to look at the bigger picture. Against India’s manufacturing capacity of $450 billion, topper China’s capacity is at a stratospheric $5.04 trillion! The United States is at number two, at $2.60 trillion. The top five is completed by countries such as Japan, Germany, and South Korea.

Even if that strange sales pitch does work on certain sections of the ignorant population, what will definitely not is the per capita manufacturing output data. According to the report, India’s per capita manufacturing output stands at a measly $318. Where do other countries fare? Germany tops the chart at $10,704, while the US is at $7,834. Forget China’s $3,569, even Brazil’s per capita output is at $1,161.

Becoming “the next China” is a long, long way off, yet. So what has gone wrong? In the early days of the republic, different states showed the capacity to produce certain goods better and at a faster pace than others, mostly because of its geographical advantages. West Bengal, for example, remained the leader in jute production, simply because the jute mills were stationed there and neighbour Bangladesh had the lion share of the jute production.

As technology and mobility advanced, these geographical advantages were diminished. Yet, there remained the necessity to build infrastructure, downstream industries and a support industrial ecosphere that provides sub-contracted items with ease and in quick time. Hence India needs to spread its manufacturing around further, each state taking up items that could complement major production houses in adjacent states. Politics has come as a major dampener in this effort, with opposition ruled states barely managing to get ahead in investment. Tamil Nadu has been an exception, because of its own effort and not because of any central bias.

The Middle Class Trap

Within this skewed manufacturing system, the markets gauged the Indian middle class wrongly. As the country opened up and industries started boosting production, domestic consumption seemed to gain speed. It was assumed that people started to have surplus income, which should lead to further and more conspicuous consumption. Not only that, some marketing agencies began believing that India’s “middle class” was 400-million strong, much larger than the entire population of the US.

Two things happened when this strange and erroneous estimate was publicised by the media. The first was the landing in India of several expensive foreign brands, believing this was going to be another China, and the second was that gullible people believed they had the right to bigger, better and more expensive things, even if their wallets did not allow it. The newly-developed debt ecosphere lent credence to such false beliefs and huge marketing spends made people with steady jobs believe that they could afford more, could take those expensive holidays, buy that car or house.

The Indian value system has never allowed for spending beyond conservative limits. That value system went for a toss. With the availability of a multitude of financial instruments, such as personal loans, credit cards and other easy access to money, personal debt soon climbed beyond proportions.

India has yet to reach anywhere near the personal debt Everest that the US has created, but, at a comparative level, the situation is pretty dire.

As of now, and according to an analysis, between 5 and 10 percent of India’s middle class have entered such a debt cycle, with multiple loans, that they are unlikely to get out of, ever. This virtually imitates what has happened in the US, where subprime people have taken new loans to service older loans. The debt trap is unending.

To make matters worse, this has come about at a time when the manufacturing sector is facing tariff barriers, exports are slipping fast, unemployment is shooting through the roof and for those still in employment, salaries have flat lined.

As of now, credit card and retail loans have gone up from 4 percent to 11 percent of the total banking system credit outstanding. This “growth” has happened in the last decade. The fact that Indian financial institutions rely a lot on the CIBIL score seems a tad erroneous. It has been said that up to 45 percent of India’s borrowers are subprime, and default is a real risk. More importantly, 48 percent of the debt absorbed by these subprime borrowers is for consumption, not asset-building.

The scenario is scarier, when you see that 67 percent of middle class Indians have taken personal loans. Servicing personal loans are scary, because they come with hefty interest rates attached.

What Is The Way Out?

As of now, the scenario is pretty much like what had happened when it was discovered that public sector banks were sitting on billions of dollars of non-performing assets (NPA). However, while the government showed the way out for banks with external funding and by allowing major debt write-offs, the individual citizen does not have such an option. Declaring personal bankruptcy isn’t a thing in India yet, and penal procedures will definitely be the only way out in an atmosphere where even reputable mutual funds are drying out.

Interestingly, the development of the manufacturing sector across the country just might help solve this problem. India may have veered more towards a service economy, but if one considers the inherent strengths of the country, and its general level of education, large manufacturing units will remain the only ones that can absorb the unemployed.

More interestingly, if the government is serious about the MSME sector—for all practical purposes, this has not been the case so far—all downstream activity of these large units can be handled by these small units, providing even more jobs. The MSME base structure still exists, and if this is exploited and the natural Indian zeal of enterprise is given the right boost, then one just might see India cross this hurdle with ease.

Finally, it depends on some good thinking by the government of the day, because the intended change is crucial. This is because, when hunger strikes, even the extravagance of a chariot race or the chilling experience of a gladiatorial show won’t cut the ice.