By Shaan Katari Libby

“Eyes down children!” was a familiar command when watching videos with our parents in our growing up years. The reason was inevitably a passionate scene. Today trying to enforce similar standards feels somewhat superfluous with access to the internet. Still, the desire to keep the young innocent for as long as possible is something most parents harbour—understandably. Films are a similar story—the whole notion of a board of persons who decide what age group should or should not have the opportunity to watch a particular film is, in theory, a responsible thing to do in a society where there are films involving sex, drugs and extreme violence. You would not want a young child exposed to these horrors.

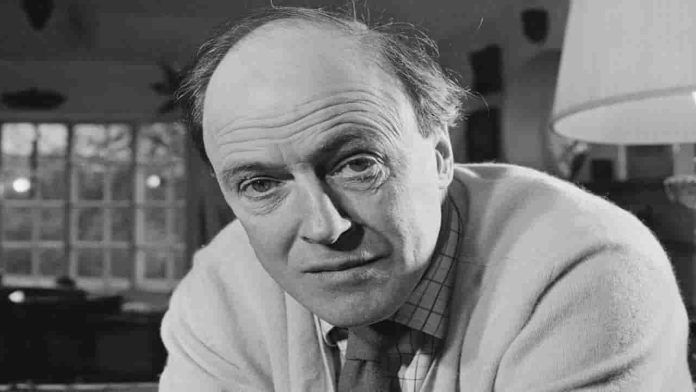

Writing has also often been trimmed of content so as to ensure it is politically correct and acceptable to the intended audience. Recently Roald Dahl’s children’s books published by Puffin Books (a division of Penguin) has been through it—Augustus Gloop is no longer “fat”, just enormous, Fantastic Mr Fox’s frightening tractor is no longer black, and the Oompa Loompas are gender neutral. Instead of teaching children that words (like fat for instance) cannot hurt them, we are sending out the signal that they can indeed hurt and so we will take away those words and protect the children of today.

Having advisory age ranges for films and TV programmes makes sense, and while Enid Blyton removing the racially stereotyped “Gollywog” was definitely needed, the sanitising of Dahl’s books is questionable. Censorship at these tender ages can, however, be understood despite it being an imperfect art. The problems arise when censorship extends to adulthood—often curtailing absolute freedom of speech and expression. Reasoning? To protect a certain class of people—the common man or those in power is the question.

The censorship of films in India is undertaken by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) set up under the Cinematographic Act, 1952. The guidelines call for films to remain responsible and sensitive to values and standards of society while ensuring artistic expression and creative freedom. Anti-social activities are not to be glorified or justified nor is the modus operandi of criminals. Scenes showing children in violence are to be avoided. So also, child abuse, animal cruelty or glorifying drinking/drugs. They seek to avoid offence by vulgarity, obscenity or depravity, avoiding scenes involving sexual violence against women or reducing them to the minimum. “Visuals or words contemptuous of racial, religious or other groups are not presented; visuals or words which promote communal, obscurantist, anti-scientific and anti-national attitude are not presented.” The term anti-national seems to be a catch all, and at the moment, it is often used whenever something is not comfortable.

The law in the Indian Penal Code of 1860, as amended today, makes it an offence to sell/distribute/publicly display or even import/export or profit from obscene books or objects if they “tend to deprave and corrupt”. Being involved in the advertising of such an enterprise is also an offence. As per an amendment, it shall not be considered an offence if it is “in the interest of science, literature, art or learning or for religious purposes”. This wide amendment narrows the scope of censorship.

In Life Insurance Corporation of India vs Prof. Manubhai D. Shah, Doordarshan refused to telecast a documentary film on the Bhopal gas disaster, titled Beyond Genocide, despite winning the Golden Lotus Award 1987. The top court said being critical of the state government or having pending matters is no reason to deny selection and publication of a film. In 2003, the Board banned the film Gulabi Aaina by Sridhar Rangayan. This film on transsexuals was considered vulgar and offensive. The filmmaker appealed unsuccessfully. The film has, however, been screened at festivals all over the world and won awards for its portrayal of marginalised communities.

In 2004, the documentary Final Solution by Rakesh Sharma on the 2002 Gujarat riots was banned as “highly provocative”. The ban was lifted in October 2004 after a sustained campaign. Even a “Pirate-and-Circulate” campaign was conducted in protest against the ban (get-a-free-copy-only-if-you-promise-to-pirate-and-make-5-copies). Over 10,000 free video CDs of the film were distributed. Kamal Haasan’s Vishwaroopam was banned for two weeks in Tamil Nadu. The film was about India’s foreign intelligence service’s participation in America’s war on terror after the 9/11 attacks by Al-Qaeda agents; several Muslim organisations protested. Heeding the requests, controversial scenes were muted or morphed, allowing the film to be released.

In 2015, filmmakers Jharana Jhaveri and Anurag Singh’s Charlie and the Coca Cola Company: Quit India was not certified and the case has been pending since. The film is about two Coca Cola plants in Mehdiganj, Uttar Pradesh, and the protests by the farmers against the over-extraction of groundwater.

In 2016, the film, Udta Punjab, produced by Anurag Kashyap and Ekta Kapoor faced trouble, resulting in a re-examination of the ethics of film censorship in India. The film, which depicted a structural drug problem in Punjab, used expletives and showed drug abuse. The CBFC released a list of 94 cuts and 13 pointers, including the deletion of names of cities in Punjab. However, the film was cleared by the Bombay High Court with one cut and disclaimers. The Court ruled that, contrary to the claims of the CBFC, the film was not meant to “malign” the state of Punjab, and that “it wants to save people”. In 2018, the film, No Fathers in Kashmir, directed by Ashvin Kumar hit a roadblock. His two previous documentaries, Inshallah, Football and Inshallah, Kashmir were first banned and subsequently awarded national awards. Kumar has written an open letter stating that being awarded an A certificate for an independent film is “as good as banning the film”.

Recently, Shah Rukh Khan’s film Pathaan was mired in controversy, due to its song Besharam Rang, for “hurting religious sentiments” of the Hindus. Several right-wing organisations objected to the “saffron costumes” worn by actor Deepika Padukone in the song—although if you watch it, she wears multiple colours throughout the song, and orange is one of them, a colour that all are free to wear. This is not the first time film stars personally have been in the throes of controversy. Padukone had starred opposite Ranveer Singh in Goliyon Ki Rasleela Ram-Leela, an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali. Her role was Leela, a Gujarati girl based on the character of Juliet. Initially titled Ram-Leela, the film’s title was changed after a court case was registered against Bhansali, Padukone and Singh for “offending the religious sentiments” of the Hindu community.

A petition, filed on behalf of one Shaheen Abdullah, said at a recent programme held in Haryana’s Mewat, thousands of Bajrang Dal members took a pledge to use “Trishul” to protect their religion. (The trishula (IAST: triśūla) is a trident, a divine symbol, commonly used as one of the principal symbols in Hinduism). A similar event was organised in Pataudi, around 25 km away. The petition said speeches inciting people against Muslims were delivered at these programmes, which is a threat to the unity and integrity of the country. Despite this, the Haryana Police did not take any action against the speakers and organisers, the petition said.

The apex court said it would also hear a petition by right-wing group Hindu Front for Justice, which wanted action against Muslims and Christians who are allegedly giving hate speeches against the Hindus. All petitions, taken together, will be heard on March 21, 2023. “Our civilisation, our knowledge is eternal and we should not belittle it by indulging in hate speech… The common enemy of all religions is hatred… Remove hate from the mind and you will see the difference,” Justice KM Joseph said. Section 298 CPC makes the uttering of words/ sounds or the making of gestures with deliberate intent to wound religious feelings of any person an offence punishable with imprisonment for up to one year, and/or a fine.

The World Press Freedom (WPF) Index calculates the degree of freedom available to journalists in 180 countries by pooling the responses of experts to a questionnaire devised by RSF and targeted to media professionals, lawyers and sociologists. The criteria are pluralism, media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information. India has slipped to 150th out of 180—we have less freedom than Turkey, Hong Kong, Colombia, Kazakhstan and Qatar, to name but a few of the 149 above us. Worse off than India according to this study are Sudan, Belarus, Pakistan and others—at least we are freer than some.

Coming finally to the recent controversy over the BBC documentary on the current prime minister of India and the concern that the world is maligning Narendra Modi and by extension India, it is fairly standard for the BBC to make these programmes—most major leaders have had two part and four-part series made about them. The good, the bad and the ugly parts. Never before has there been such a furore over it. Ironically, the defensive attitude and the immediate censoring of it made people in India and the whole diaspora across the world more inclined to watch it than if the government had simply shrugged if off and let it pass without any comment…people would have soon lost interest.

Different countries handle their freedoms differently—there are harsh jokes made about British politicians—there was even a poll on Twitter by a tabloid on who would last longer—the embattled Prime Minister Liz Truss or a lettuce? The ability to laugh at oneself, to not take ourselves too seriously, to have the confidence to be aware that we do not know it all. This humility is a strength—not a weakness. Suppressing things, sitting on the media, naming and shaming critics only shows insecurity to face up to realities or to accept another’s point of view. Which is a misuse of the law and authority.

In the words of Justice Chauhan in S. Khushboo vs Kanniammal & Anr (2010): “Even though the constitutional freedom of speech and expression is not absolute and can be subjected to reasonable restrictions on grounds such as ‘decency and morality’ among others, we must lay stress on the need to tolerate unpopular views in the socio-cultural space.” He went on to speak of the framers of our Constitution and how they had recognised the importance of safeguarding this right “…the free flow of opinions and ideas is essential to sustain the collective life of the citizenry.”

—The writer is a barrister-at-law, Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, UK, and a leading advocate in Chennai. With research assistance from Jumanah Kader and Mahesh Sudhakaran