By Sujit Bhar

The Delhi High Court’s recent and significant order protecting the personality and publicity rights of Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev, the founder of the Isha Foundation, opens up multiple avenues of debate regarding the legal aspects of such acts in a country where unique personalities have rarely, if ever, been protected.

If anything, this order, in the absence of existing legislation in the field, marks a watershed moment in the evolving dialogue between technology, law and individual identity in India. In a way, the order also reflects a judicial awakening to the realities of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven impersonation, deepfakes, and unauthorised commercial exploitation of public figures.

To be precise, this order and allied paraphernalia, signals the urgent need for India to formulate clear legal provisions safeguarding personality rights—especially in the digital and AI age.

THE SADHGURU CASE AND A LEGAL VACUUM

Jaggi Vasudev had approached the Delhi High Court seeking protection of his personality rights from infringement by rogue websites and unknown entities that had misused his image, name, voice and likeness using advanced AI tools. These platforms, often operating with anonymity and impunity, created and disseminated manipulated content that distorted his public image, potentially harming both his personal brand and the trust reposed by millions of his followers.

Justice Sanjeev Narula, in his detailed order, restrained the infringing parties from exploiting Sadhguru’s persona and ordered the suspension and takedown of specific YouTube channels and social media accounts, directing platforms to disclose subscriber and ownership details. Notably, the Court emphasised that if such misuse is not checked, “it will soon spread like a pandemic…with hardly any water left to douse it”.

India, as of now, does not have a codified statute specifically safeguarding personality or publicity rights—the rights of a person to protect their image, name, likeness and other distinguishing traits from unauthorized commercial exploitation.

While these rights are often derived from Article 21 of the Constitution (Right to Privacy and Personal Liberty), and from tort law concepts such as “passing off” or defamation, they remain scattered, ambiguous, and inconsistently enforced.

Courts have intermittently recognized personality rights in high-profile cases:

- Titan Industries vs M/s Ramkumar Jewellers (2012): The Delhi High Court restrained the defendant from using a print advertisement featuring Bollywood actors Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan without authorization. The Court held that even if the image was publicly available, its use for commercial benefit without consent was unlawful.

In this, the Court observed that by virtue of Section 17 (b) of the Copyright Act, 1957, the plaintiff is the first owner of the copyright in the said advertisement and that the plaintiff has an exclusive license from Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bachchan. Hence here the Copyright Act was brought into play.

- ICC Development vs Arvee Enterprises (2003): The Delhi High Court distinguished between “broadcast rights” and “publicity rights,” holding that commercial use of a celebrity’s persona required consent, even if the underlying event was not owned by the celebrity.

- Shahrukh Khan vs SBN Film: The actor successfully secured a stay against a film that used his image for promotional activities without consent.

- Gautam Gambhir vs DAP & Co (2017): The court emphasized that if a public figure’s name is being used misleadingly in a commercial context, it infringes on their personality rights.

WHAT OF SADHGURU IS BEING PROTECTED?

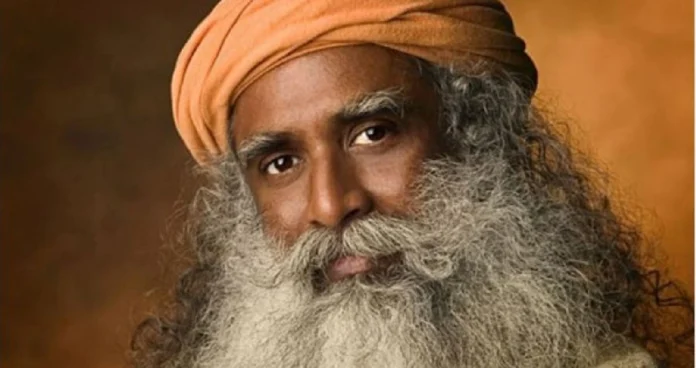

Over the years Sadhguru has carefully cultivated a unique identity, distinguishable through:

- Name, recognition as a spiritual leader.

- His distinctive voice and speech patterns, often calm, rhythmic and philosophical.

- Iconic attire, including flowing robes and a turban, often paired with his white beard and serene demeanour.

- A large following across YouTube, podcasts, international forums, and social media.

- Frequent appearances at global summits (such as Davos) and in conversations with figures like Will Smith and Karan Johar.

This curated persona forms a valuable intangible asset, which makes it prone to manipulation and misappropriation, especially with AI tools that can simulate his voice, mannerisms, or even fabricate interviews and speeches.

The rise of deepfake technology, voice synthesis and generative AI tools such as text-to-video models has dramatically amplified the risk of identity misuse, especially for celebrities. In Sadhguru’s case, unauthorised platforms generated AI-modified content that used his voice and appearance to issue misleading messages, sometimes for commercial gain or ideological manipulation.

This is part of a wider global phenomenon where:

- AI tools clone voices and faces, often indistinguishable from reality.

- Public figures are shown making statements they never made.

- Users online “puppet” celebrities to endorse products, causes, or misinformation.

- Avatars of celebrities appear in virtual spaces like games or the metaverse without permission.

India’s current laws—including the Information Technology Act, 2000, and various IP statutes—do not squarely address these issues. While defamation, copyright, or misrepresentation laws might apply tangentially, they don’t pre-emptively prevent the harm or provide swift remedies.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE COURT ORDER

The Delhi High Court’s proactive stance might serve as a blueprint for future legal developments. They would include the following:

1. Acknowledging AI misuse as a separate legal problem.

2. Reinforcing the need to treat personality traits as proprietary assets.

3. Suggesting platform liability for hosting infringing content.

4. Empowering the judiciary to direct government departments like MEITy to enforce digital compliance.

These elements may form the foundation for a new legislation, akin to the US’s Right of Publicity statutes or the EU’s Digital Services Act.

THE FLIP SIDE

However, the Delhi High Court’s broad directions—especially to MeitY and social media platforms to block accounts and websites—raise legitimate concerns about overreach and censorship.

Comedy, satire, impersonation and mimicry are long-established forms of expression, often used to critique or entertain. Comedians and content creators frequently imitate political or spiritual figures as part of their routines.

If such orders are interpreted too broadly, they could:

- Stifle legitimate creative expression.

- Lead to selective takedowns targeting dissent.

- Make comedy, parody, or impersonation legally risky even when done in good faith.

To prevent misuse of power and protect free expression, any new legal framework should incorporate the following safeguards:

1. Fair use/transformative use exception:

- Parody, satire, news reporting, and academic use must be exempted.

- Inspired by US and EU frameworks on freedom of artistic expression.

2. Transparency in takedown process:

- Orders to block content or accounts must be judicially reviewed and publicly disclosed.

- Affected parties must have a right to appeal.

3. Defined scope for AI-generated misuse:

- Legislation should specify what constitutes malicious impersonation using AI (e.g., commercial exploitation vs artistic interpretation).

4. Obligations on platforms, not blanket powers:

- Rather than giving MeitY blanket powers, assign responsibility to platforms under due process, including prompt notice to accused users, technical mechanisms to detect and flag potential misuse and regular compliance audits.

5. Independent Oversight Mechanism:

- It will be necessary to establish a digital rights tribunal or ombudsman with enough powers to ensure unbiased enforcement and address grievances.